How Do Autonomous Vehicles Perform “Scene Understanding”?

![]() 12/11 2025

12/11 2025

![]() 495

495

The term “scene understanding” might seem a bit abstract, but in the realm of autonomous driving, it essentially pertains to whether a vehicle can genuinely comprehend what's transpiring after perceiving its surroundings. To clarify this notion, merely focusing on the number of objects the perception system can recognize is insufficient. The crux lies in transforming “what is seen” into “useful information” so that the decision - making and control modules can execute safe and reliable actions based on this information.

What exactly constitutes scene understanding? And why is it so crucial?

Scene understanding entails integrating all observable information on the road to form an “understanding” of the current situation. It transcends simply detecting individual elements like pedestrians, vehicles, lane markings, and traffic signs. It also necessitates clarifying the relationships between these objects, their potential future movements, and identifying which information is most critical for the next decision. For instance, if a cyclist is riding along the side of the road, the scene understanding system should be capable of determining whether they are preparing to stop, turn, or might suddenly ride against traffic. At complex intersections, it must recognize traffic light states, understand the intentions of all parties, and ascertain which trajectories are safe and feasible.

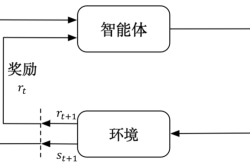

To achieve better scene understanding, every action taken by the decision - making layer must rely on abstract information provided by the upper layers. The perception system is solely responsible for converting pixels or point clouds into “facts.” However, if these facts are not organized into a “world model” with “uncertainty assessments,” the planning module may make decisions based on incorrect or unstable information, leading to potential dangers. A proficient scene understanding system can transform noisy, partially missing, or even temporarily contradictory perception outputs into stable, coherent semantic information with confidence levels for utilization by the planning and control modules.

How to Describe the World—Representation Learning and Multi - Level Semantics

The first issue that scene understanding must tackle is how to describe the world. The images, point clouds, radar echoes, and IMU data output by sensors are too raw and low - level to be directly used for decision - making, as doing so would be both inefficient and hazardous. We need to abstract them into forms suitable for autonomous driving, taking into account multiple dimensions.

Spatial geometric information forms the foundation. The three - dimensional positions, velocities, orientations, and bounding boxes of objects are essential for any motion planning. Based on these data, collision detection, lane keeping, and speed control can be carried out. Point clouds and stereo vision/depth information are the primary sources for constructing geometric representations, while visual systems can also estimate depth through multiple perspectives and neural networks.

Semantic information represents a higher level of expression. Upgrading “this is a car/pedestrian/bicycle” to “this is a truck merging lanes/a pedestrian pushing a stroller/a ride - hailing car parked on the side of the road” directly impacts how the system processes it. Semantics need to be more detailed, incorporating behavioral patterns such as constant speed, acceleration, deceleration, and head turning. In Western traffic culture, for example, pedestrians usually follow strict crosswalk rules, and understanding these semantic behavioral patterns helps the autonomous system better predict and respond to pedestrian actions.

The relationships and intentions between objects also need to be represented. Their relative positions, potential occlusion relationships, who is relatively passive, and who poses a higher risk are all focal points of scene understanding. For example, if a car parked on the side of the road opens its door, the relationship between the “door” and “adjacent pedestrians” becomes far more important than the “door” as an isolated object. Intentions involve probabilistic predictions of an object’s future behavior, typically not providing a single definite trajectory but several possibilities along with their respective confidence levels. This is similar to how human drivers anticipate the actions of other road users based on their past behavior and current situation.

Representation of the temporal dimension is also crucial. Traffic scenes are not static but continuously evolving processes. Using historical trajectories to estimate an object’s inertia and behavioral patterns can improve the accuracy of predicting its future movements. Many systems design representations as temporal graphs, trajectory clusters, or hidden state vectors, allowing the planning module to see “how this pedestrian has moved over the past few seconds and thus infer what they might do next.”

Additionally, there is the representation of multi - modal fusion. Different sensors have varying reliability under different conditions, and scene representations need to fuse this information while reflecting uncertainties. An ideal representation includes both precise geometric information and high - level semantic labels with probabilistic uncertainty descriptions, capable of rapid updates within real - time constraints. This is akin to how humans use multiple senses (sight, hearing, etc.) to gather information about the environment and make decisions.

From Data to Reasoning—The Integration of Learning, Prediction, and Logical Reasoning

With an appropriate representation method in place, the next step is how to train systems from data that can generate these representations and how to combine learned patterns with logical rules during reasoning.

In this process, data is fundamental, but data alone does not equate to understanding. Labeled data can train models for object detection, segmentation, and trajectory prediction. However, the diversity of real - world scenes means that insufficient or biased data can cause models to fail in edge cases. Therefore, multi - source data is required, including real road data, simulation - generated data, synthetic data, and data specifically collected for edge cases. Self - supervised and unsupervised representation learning are directions to reduce reliance on labeling. By having models learn patterns such as motion consistency and object permanence from unlabeled videos, generalization capabilities can be improved. This is similar to how humans learn from a wide range of experiences, not just labeled examples.

Model selection and architecture design directly impact understanding capabilities. End - to - end large models can learn mappings from pixels to control but suffer from poor interpretability and verifiability. Modular architectures separate perception, tracking, prediction, scene understanding, and decision - making, facilitating engineering, troubleshooting, and incremental verification. Many systems adopt hybrid approaches, using deep learning for perception and short - term prediction, then employing symbolic rules, behavior trees, or model - based reasoning for safety - related constraints and long - term planning. This is like having a team where different members have specialized skills and work together to achieve a common goal.

Uncertainty modeling is essential. Scene understanding cannot provide only a single definite answer but must also offer confidence levels and possible alternative explanations. Common methods include Bayesian approaches, probabilistic graphical models, Monte Carlo sampling, Gaussian process - based predictions, or leveraging neural network output distributions (e.g., predicting multiple possible modes with weights). The planning layer adjusts its conservatism based on these uncertainties, such as slowing down at uncertain intersections or increasing safety distances. This is similar to how humans are more cautious when they are unsure about a situation.

Causal reasoning and rule constraints enhance system robustness. Learning models excel at capturing statistical correlations but sometimes require judgments based on physical laws and traffic rules, such as longer braking distances on slippery roads or not turning right at a red light without special markings. Embedding physical models, traffic regulations, and common - sense rules into the system can serve as a “last line of defense” when learning models fail. This is in line with how human drivers follow traffic rules and use common sense to make safe decisions.

Online learning and closed - loop updates are also crucial. Vehicles encounter new scenes, and the system needs to collect failed samples, label them, and retrain or adopt lighter online adaptation methods for rapid model adjustments. From an engineering perspective, this involves data collection, labeling processes, simulation verification, and deployment strategies, which are key to whether the scene understanding system can continuously improve. This is similar to how humans learn from new experiences and adjust their behavior over time.

Engineering Practice—Real - time Performance, Robustness, and Verifiability

Even if scene understanding has a theoretically perfect representation method and excellent models, it must still face stringent engineering constraints to be truly implemented in vehicles. One of the cores of scene understanding is how to achieve accuracy and verifiability within limited computational resources and strict real - time requirements.

Real - time performance means the system must complete perception, understanding, and prediction within a few hundred milliseconds or less, then deliver results to the planning module. Therefore, representation methods and models often require engineering compromises, such as using sparse representations to reduce computation, candidate sampling instead of full - space searches, lightweight networks for preliminary screening, and sending key regions to heavy models for detailed reasoning. Hardware co - design is also critical; placing key computations on dedicated accelerators or automotive - grade SoCs can significantly improve throughput and energy efficiency. This is similar to how a well - organized team can work efficiently under time pressure.

Enhancing the robustness of scene understanding requires enabling autonomous driving systems to easily handle various challenges such as sensor failures, adverse weather, occlusions, and adversarial conditions. Sensor degradation strategies, redundancy between sensors, and model - based uncertainty detection can all improve overall robustness. If the visual system fails in thick fog, millimeter - wave radar and lidar can provide geometric information; if a sensor drops packets, the system should quickly switch to a backup strategy and notify the planning layer to tighten safety boundaries. This is similar to how humans rely on different senses and backup plans when faced with difficult situations.

Verifiability and interpretability are crucial for safety. Both regulation and productization require demonstrating that the system is safe under specific conditions. Modular design facilitates formal verification by transforming some safety - critical judgments into verifiable assertions (e.g., maintaining a minimum following distance) and conducting coverage testing with extensive simulations and scenario libraries. Additionally, fault logging and traceable diagnostic mechanisms are needed so that when scene understanding makes erroneous judgments, the cause—whether perception errors, representation mistakes, or model generalization issues—can be quickly identified. This is similar to how in engineering projects, clear documentation and fault - tracking systems are essential for quality control.

Simulation plays a significant role in engineering practice. It is difficult to collect all rare edge cases in the real world, but high - fidelity simulations can create complex interactions, extreme weather, and dangerous situations to verify system responses. Combining simulation with real data and using simulation - generated data for training or testing can accelerate the improvement of scene understanding capabilities. This is similar to how in scientific research, simulations are used to test theories and predict outcomes.

Finally, attention must be paid to verification coverage and data distribution bias. No system can pass verification for “all scenarios,” but a risk - prioritized approach can be taken. Verification resources can be allocated to the most dangerous or common failure modes, establishing a dynamically updated risk catalog to continuously incorporate newly identified issues into training and testing processes. This is similar to how in risk management, resources are focused on the most critical risks.

Final Remarks

The core of scene understanding is not a single technology but a set of tightly coupled capabilities: appropriate world representation, learning and reasoning based on rich data and reasonable architectures, and real - time performance, robustness, and verifiability for practical applications. It requires both the expressive power of deep learning and constraints from physical models and rules, along with a complete data closed loop for continuous improvement.

For engineering teams, scene understanding is a long - term effort that requires phased advancement. Every optimization of representation, every additional collection of edge case data, and every improvement in verification coverage directly enhances vehicle performance on real roads. Transforming “seeing” into “understanding” and then into “reliable actions” is the core path for the safe implementation of autonomous driving.

-- END --