Is a Higher 'Line Count' in LiDAR Synonymous with Enhanced Autonomous Driving Capabilities?

![]() 01/23 2026

01/23 2026

![]() 456

456

In the realm of autonomous driving technology, LiDAR has long been hailed as a cornerstone perception hardware, with its line count often serving as a key metric for gauging perception prowess. From the early days of 16-line and 32-line models to the current standard of 128-line and 192-line systems in mass-produced vehicles, and even the latest 512-line iterations, the industry appears to be embroiled in a 'line count' arms race, suggesting that more lines equate to superior autonomous driving capabilities. But is this truly the case?

The Essence of LiDAR Line Counts

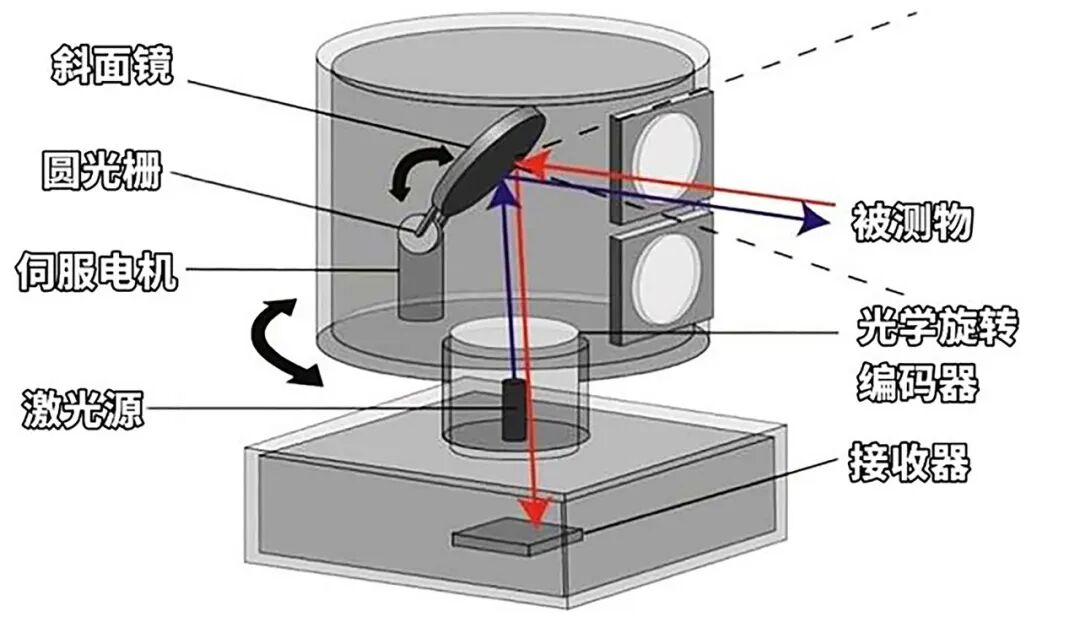

The line count of LiDAR, also known as the number of channels, denotes the quantity of laser beams distributed within its vertical field of view (FOV). For traditional mechanically rotating architectures or the more prevalent solid-state LiDAR systems, the line count essentially mirrors the number of laser transceiver module groups integrated within the radar. Each physical channel represents an independent ranging unit, and as the scanning mechanism oscillates or rotates, these lines can trace dense ranging trajectories in space. The most direct benefit of increasing line counts is a marked improvement in vertical angular resolution. Angular resolution refers to the angular interval between two adjacent detection points; a smaller interval translates to a denser array of laser points projected onto a distant target object.

Image Source: Internet

In the perception tasks of autonomous driving, the divergence of laser beams with increasing distance leads to a rapid decline in point cloud density per unit area, making the identification of small, distant targets a persistent challenge for the industry. A 16-line radar detecting a pedestrian 150 meters away might only capture one or two sparse points on the target, which the backend algorithm might dismiss as mere noise. However, when the line count escalates to 128 lines or higher, dozens or even hundreds of points can be projected at the same distance, delineating a complete human silhouette or limb movements. This leap in resolution significantly eases the burden on perception algorithms in handling edge cases. Experimental data reveals that when detecting a small target measuring 10 centimeters, a 16-line radar can only identify it at a distance of about 3 meters, whereas when the equivalent line count increases to the 300-600 line range, the effective identification distance can soar to over 100 meters.

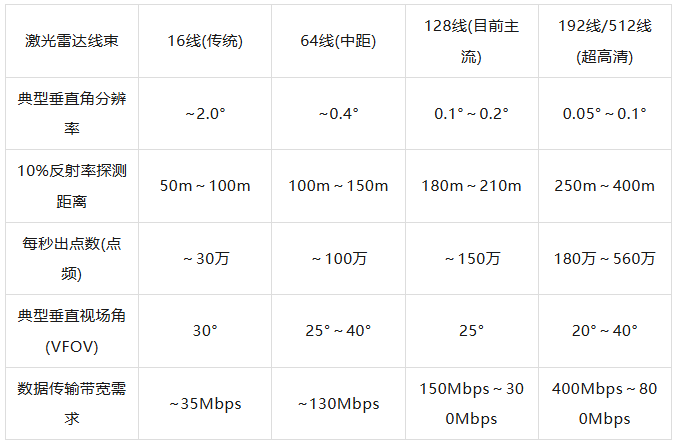

Comparison of Key Parameters for LiDAR with Different Line Counts

This performance enhancement also holds irreplaceable value in terms of safety redundancy. High-line-count LiDAR, with its multitude of independent transmit and receive channels, inherently possesses anti-failure capabilities at the hardware level. For instance, the Hesai AT128 integrates 128 independently operating lasers; even if a few channels malfunction, the remaining channels can still ensure the continuity and completeness of the overall perception scene, averting perception blind spots. Of course, this 'physical stacking' approach is not without its challenges. Cramming hundreds of modules into LiDAR with discrete components not only causes the volume to balloon like a 'large flowerpot,' making it difficult to integrate into the vehicle body, but also drives costs to levels that automakers find unsustainable. Therefore, the current autonomous driving industry is exploring chip-based solutions, leveraging semiconductor processes to integrate a large number of transmitters and detectors onto centimeter-scale chips, achieving a balance between high line counts and compact volume through silicon photonics technology.

Systemic Pressures and Marginal Costs Behind High Line Counts

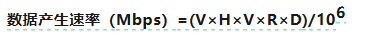

As the line count of LiDAR increases, the vehicle's electrical and electronic architecture faces unprecedented strain. The surge in line counts is not an isolated parameter change; it triggers a cascade of reactions in computational power, bandwidth, power consumption, and thermal management. The first hurdle is data transmission bandwidth. The data generation rate (Mbps) of a LiDAR can be quantitatively estimated using a core formula:

Where N refers to the line count or number of channels; H refers to the number of horizontal points, calculated as horizontal field of view (FOV) / horizontal angular resolution; V refers to the frame rate (e.g., 5Hz, 10Hz, or 20Hz); R refers to the number of echoes; and D refers to the number of bits per data point (Bit).

According to this formula, when the line count evolves from 128 lines to 256 lines or 512 lines, the number of point clouds generated per second skyrockets from the million level to over five million. This means the in-vehicle Ethernet needs to handle real-time data streams approaching 1Gbps. For mass-produced vehicles still widely using gigabit Ethernet architectures, multiple LiDAR configurations can easily cause bus congestion.

The escalation in LiDAR line counts also exerts pressure on the computing platform. Autonomous driving systems must preprocess, cluster, detect targets, and perform semantic segmentation on these disordered 3D point clouds in real time. The time complexity of mainstream 3D perception algorithms (such as VoxelNet or Transformer-based architectures) increases nearly linearly with the number of input points. If the computing power of the intelligent driving chip is insufficient, the massive point clouds will cause processing delays exceeding the 100-millisecond closed-loop threshold, posing serious driving safety risks.

Computational Power Estimation for LiDAR Processing Tasks

In engineering practice, to maintain real-time performance, 'downsampling' or random point dropping is often enforced at the front end of the perception algorithm. This essentially means that the high line count radar, purchased at a premium by automakers, has its increased line numbers 'negated' at the software level due to computational power constraints, resulting in the hardware-level benefits of line counts not being effectively translated into actual perception accuracy improvements—a classic case of diminishing marginal returns.

Additionally, high line count radars face severe challenges with peak current and heat accumulation due to their extremely high laser pulse emission frequencies. On the 1550nm long-wavelength route, the low electro-optical conversion efficiency of the laser generator can lead to heat dissipation demands that may even approach the power distribution limits of the 48V in-vehicle power supply network, forcing automakers to design more complex liquid cooling systems, further escalating vehicle costs.

Beyond cost and computational power, the physical environment also imposes constraints on high line count radars. While more lines provide clearer visibility in clear weather, performance drops sharply in heavy rain, dense fog, or blizzards. Mie scattering caused by water droplets generates a large number of false noise point clouds, potentially producing over 2000 false target points per second, instantly drowning out real obstacle information. In such extreme scenarios, increasing line counts does not improve perception accuracy; instead, high line count radars, being more sensitive to weak signals, may generate more false alarms in harsh weather, triggering unnecessary emergency braking.

Technological Transformations in LiDAR Detection Architectures

Given the apparent bottlenecks of blindly stacking physical line counts, the autonomous driving industry is seeking smarter solutions. One of the most representative trends is shifting from 'uniform panoramic scanning' to 'dynamic perception allocation,' also known as ROI (Region of Interest) technology or 'gaze' mode. The core of this technology is no longer mindlessly increasing the physical number of lasers but using algorithms to control the scanning mechanism in real time.

For example, certain technical architectures from RoboSense and Huawei allow LiDAR to concentrate most of its scanning lines in the central vertical FOV region when the vehicle is traveling at high speeds. This is akin to human eyes: while peripheral vision can see the surroundings, the focal attention locks onto obstacles ahead. This architecture enables LiDAR to instantaneously increase local vertical resolution by 4 to 5 times without changing the physical total line count, achieving an equivalent effect of hundreds or even thousands of lines. This approach of allocating resources on demand not only solves the resolution challenge for long-distance detection but also avoids wasting expensive bandwidth and computational power on unimportant areas like the sky or road surface. This shift marks LiDAR's formal entry into the digital age.

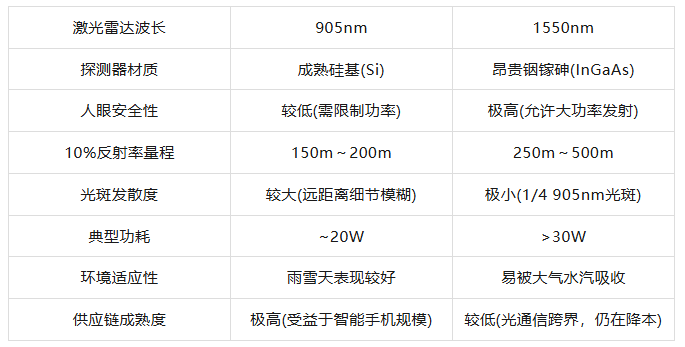

Another technological variable in LiDAR is wavelength selection. Currently, there are two mainstream wavelengths for LiDAR on the market: 905nm and 1550nm. The 905nm wavelength has a significant cost advantage due to its compatibility with mature silicon-based receivers, but it is strictly limited by human eye safety power constraints, posing a natural 'ceiling' when increasing line counts and detection range.

In contrast, the 1550nm wavelength laser operates outside the absorption band of the human retina, allowing the use of emission power dozens of times higher than 905nm. This enables 1550nm radars to achieve stronger penetration and longer detection ranges without increasing line counts, even enabling ultra-long-range perception. Although 1550nm LiDAR currently faces issues such as high fiber laser costs, large volumes, and difficult heat dissipation, its potential in ultra-high-definition perception is widely recognized as the supply chain matures.

Comparison of 905nm vs. 1550nm LiDAR

Furthermore, with the rise of FMCW (Frequency-Modulated Continuous Wave) LiDAR, a paradigm shift is underway on traditional ToF (Time-of-Flight) LiDAR. Traditional ToF radars can only measure object distance, while FMCW measures the frequency difference between the reflected wave and a reference wave, directly obtaining the object's instantaneous radial velocity through the Doppler effect. This means FMCW LiDAR, even with lower line counts, can precisely filter out static noise using fourth-dimensional velocity information, identifying pedestrians crossing the road or vehicles suddenly cutting in. This '4D perception' capability significantly reduces the reliance of backend perception algorithms on high-density point clouds, offering another avenue to break free from the line count race.

Software-Defined Radar and Next-Generation Perception Trends

As the growth rate of hardware line counts gradually plateaus, artificial intelligence is stepping in to enhance perception capabilities at the software level. Currently, much research is focused on point cloud super-resolution (Super-Resolution) algorithms. These techniques leverage deep convolutional neural networks or models like SRMamba to perform feature learning and geometric reconstruction on sparse point clouds output by low line count radars. By training on large-scale high-definition point cloud datasets, AI can learn the patterns of real-world 3D structures, thereby 'completing' raw data from 32-line or 64-line radars to an equivalent fine resolution of 128 lines or higher.

With the application of cross-modal fusion technology, advanced perception frameworks can deeply couple the sparse 3D information from LiDAR with the 2D high-definition images from onboard cameras. Using edge details and color features from the images, algorithms can provide 'semantic cohesion' to the discrete point clouds, generating environmental models that combine both 3D depth and image-level resolution. This means that instead of mounting an expensive 512-line radar on the roof, a cost-effective 128-line radar paired with a powerful AI inference engine can achieve perception effects beyond physical limits. This 'software-hardware integration' approach is considered the inevitable path to breaking the current hardware cost bottlenecks in autonomous driving and achieving 'intelligent driving equality.'

Of course, in the safety-critical field of autonomous driving, 'certainty' must always take precedence. While generative algorithms can enhance image clarity, they may also produce 'hallucinations,' such as filling in non-existent structures in sparse point cloud regions or misidentifying a real small obstacle as background noise for smoothing.

Final Thoughts

The evolution of LiDAR line counts in autonomous driving has transitioned from a mere 'quantity competition' to a 'quality competition' phase. For L2+-level mass-produced passenger vehicles, considering cost and computational power constraints, 128 lines supplemented by ROI dynamic scanning may become the industry mainstream. For L4-level Robotaxi, to meet extreme safety challenges, ultra-high-definition line count radars with deep multi-sensor fusion remain an insurmountable moat. More lines in LiDAR do not necessarily equate to better performance; only when sensor specifications, vehicle computational power platforms, backend perception algorithms, and ultimate business logic form a systematic closed loop does such technology hold true value.

-- END --