Revealing the Truth Behind 'Super Nodes': Without Unified Memory Addressing, They're Just Server Piles

![]() 02/02 2026

02/02 2026

![]() 525

525

As trillion-parameter multimodal large models become the norm, the AI industry's 'arms race' has evolved. It's no longer solely about ramping up model parameters and piling servers; it's about delving deep into the underlying computing architecture and initiating a 'system-level showdown.'

Consequently, 'super nodes' have emerged as the new darlings of the computing sector.

To date, over a dozen domestic firms have unveiled their 'super nodes,' but their approaches are flawed. Simply cramming dozens of servers into a single cabinet and linking them with optical fibers doesn't cut it. Labeling them as 'super nodes' and claiming to have shattered Moore's Law is misleading.

After delving into the technical intricacies of multiple 'super nodes,' we've uncovered a stark reality: without 'unified memory addressing,' these so-called 'super nodes' are imposters, still relying on traditional server-stacking architectures.

01 Why Are Super Nodes Necessary? The Root Lies in the 'Communication Barrier'

Let's start from the beginning: Why has the Scale Out cluster architecture, a staple in the internet era for over two decades, become obsolete in the era of large models?

The China Academy of Information and Communications Technology shed light on this in its 'Super Node Development Report' released a few months ago, summarizing the reasons as 'three barriers':

The first is the communication barrier. In large model training, communication frequency soars exponentially with model layers and parallelism. Microsecond-level protocol stack delays accumulate over trillions of iterations, leaving computing units idle for extended periods and directly capping computing power utilization.

The second is the power consumption and cooling barrier. To mitigate delays and waiting times, engineers have resorted to cramming as many computing units as possible into a single cabinet, at the expense of immense cooling pressure and power supply challenges.

The third is the complexity barrier. The 'brute force' approach of hardware stacking has pushed cluster sizes from thousands to tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of cards, but operational complexity has surged proportionally. In large model training, faults arise every few hours.

The real-world challenge is that large models are transitioning from single-modal to full-modal fusion, with context lengths reaching megabytes, training data soaring to 100TB, and latency requirements under 20 milliseconds for scenarios like financial risk control. Traditional computing architectures have become visible bottlenecks.

To meet these new computing demands, breaking the 'communication barrier' is imperative. Beyond server stacking, are there other paths?

Let's first examine the technical principles behind the 'communication barrier.'

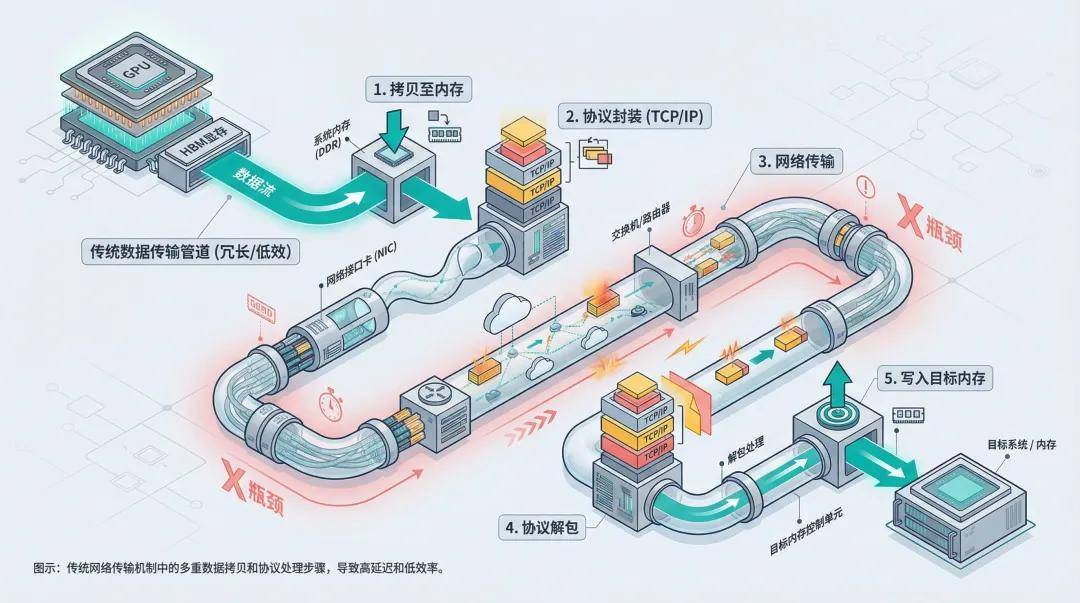

In traditional cluster architectures, the principles of 'separation of storage and computing' and 'node interconnection' reign supreme. Each GPU is an isolated island with its own independent territory (HBM memory) and only understands 'local language.' When it needs to access data from a neighboring server, it must navigate a cumbersome 'diplomatic process':

Step 1: Data movement. The sender copies data from HBM to system memory.

Step 2: Protocol encapsulation. The data is sliced and wrapped with TCP/IP or RoCE packet headers.

Step 3: Network transmission. The data packets are routed through switches to the target node.

Step 4: Unpacking and reassembly. The receiver parses the protocol stack and strips the packet headers.

Step 5: Data writing. The data is finally written to the memory address of the target device.

This process, known academically as 'serialization-network transmission-deserialization,' introduces several milliseconds of delay. For web requests, this delay is negligible. However, in large model training, where the model is divided into thousands of blocks and each layer of neural network computation requires high-frequency synchronization between chips, it's like having to call a neighboring classmate to confirm every digit when solving a math problem—efficiency plummets.

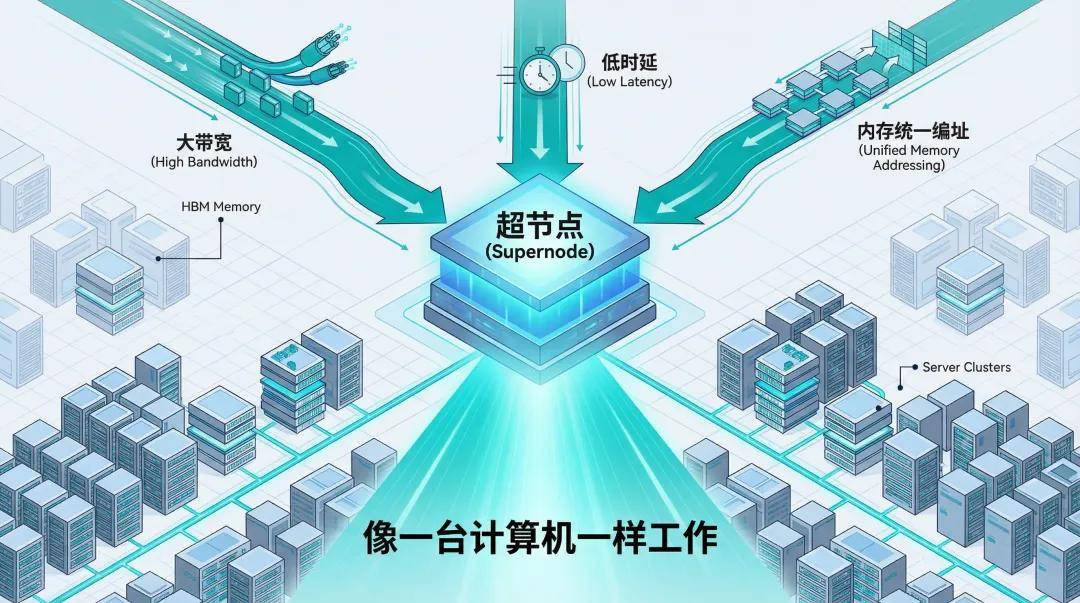

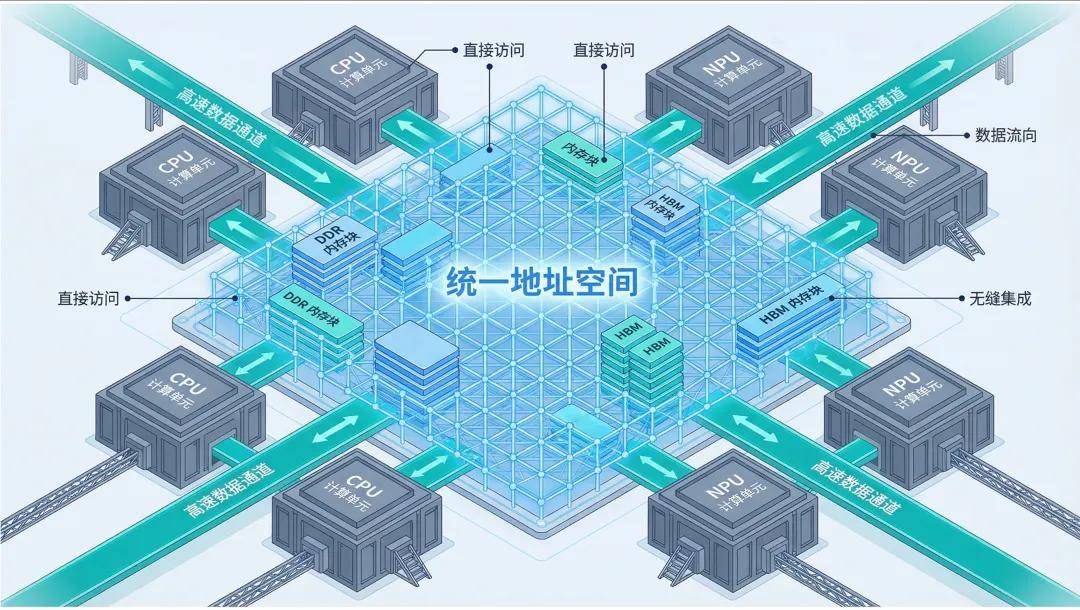

The industry's response has been to propose the concept of 'super nodes' and define three hard requirements: high bandwidth, low latency, and unified memory addressing.

The first two concepts are straightforward: widen the road (high bandwidth) and make the car run faster (low latency). The most critical and challenging aspect is 'unified memory addressing': the goal is to construct a globally unique virtual address space where the memory resources of all chips in the cluster are mapped into a single vast map. Whether the data resides in its own memory or in the memory of a neighboring cabinet, for the computing unit, it's just a matter of address difference.

Similarly, when solving a math problem, there's no need to 'call' a neighboring classmate; instead, data can be directly 'reached out for.' The overhead of 'serialization and deserialization' is eliminated, the 'communication barrier' disappears, and computing power utilization sees room for improvement.

02 Why Is Unified Memory Addressing Challenging? The 'Generational Divide' in Communication Semantics

Since 'unified memory addressing' has been proven to be the correct path, why do some 'super nodes' on the market still rely on server stacking?

The divide is not just in engineering capabilities but also in the 'generational divide' in communication semantics, encompassing communication protocols, data ownership, and access methods.

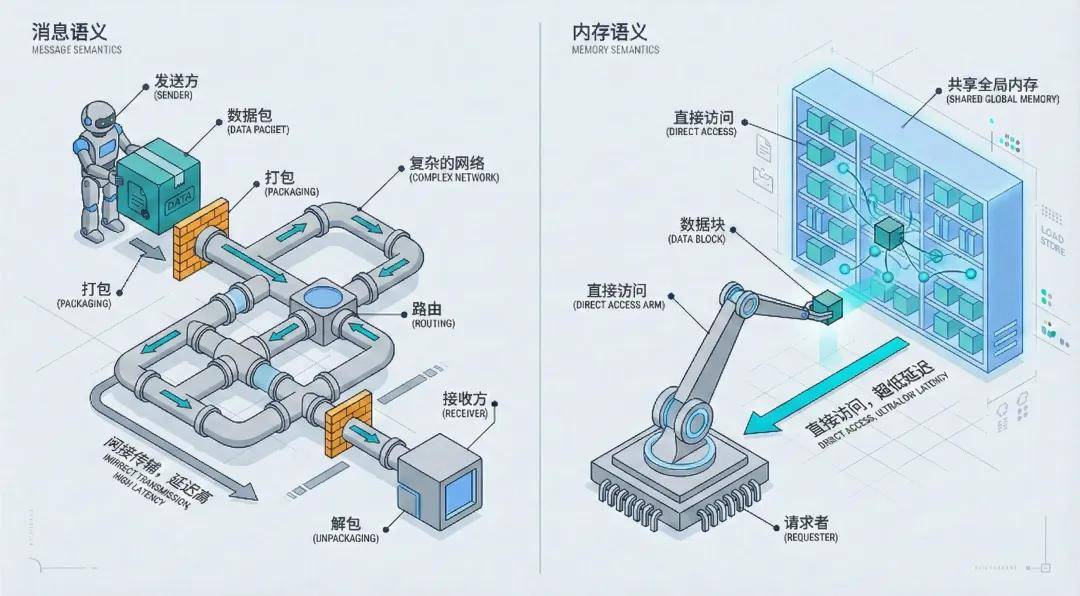

Currently, there are two mainstream communication methods.

One is message semantics for distributed collaboration, typically embodied by send and receive operations, akin to 'sending a package.'

To transfer a book, one must first pack and seal it (construct a data packet), fill out a shipping label with the recipient's address and phone number (IP address, port), call a courier to send it to a logistics center (switch), have the recipient unpack and retrieve the book (unpack), and finally have the recipient reply with 'received' (ACK confirmation).

Even if the courier runs very fast (high bandwidth), the time spent on packing, unpacking, and intermediate handling (delay and CPU overhead) cannot be saved.

The other is memory semantics for parallel computing, typically embodied by load and store instructions, akin to 'taking a book from a bookshelf.'

To transfer a book, one simply walks to a public bookshelf, reaches out and takes it down (Load instruction), and puts it back after reading (Store instruction). There's no packing, no filling out forms, and no 'middleman markup'—the efficiency improvement is self-evident.

Protocols like TCP/IP, InfiniBand, and RoCE v2 support message semantics and are direct causes of the communication barrier. However, protocols like Lingqu and NVLink already support memory semantics. If that's the case, why can't 'pseudo-super nodes' achieve unified memory addressing?

Because the crown jewel of memory semantics is 'cache coherence': if Node A modifies data at shared memory address 0x1000, and Node B has a copy of that address in its L2 cache, it must ensure that Node B's copy is immediately invalidated or updated.

To achieve 'memory semantics,' two conditions must be met:

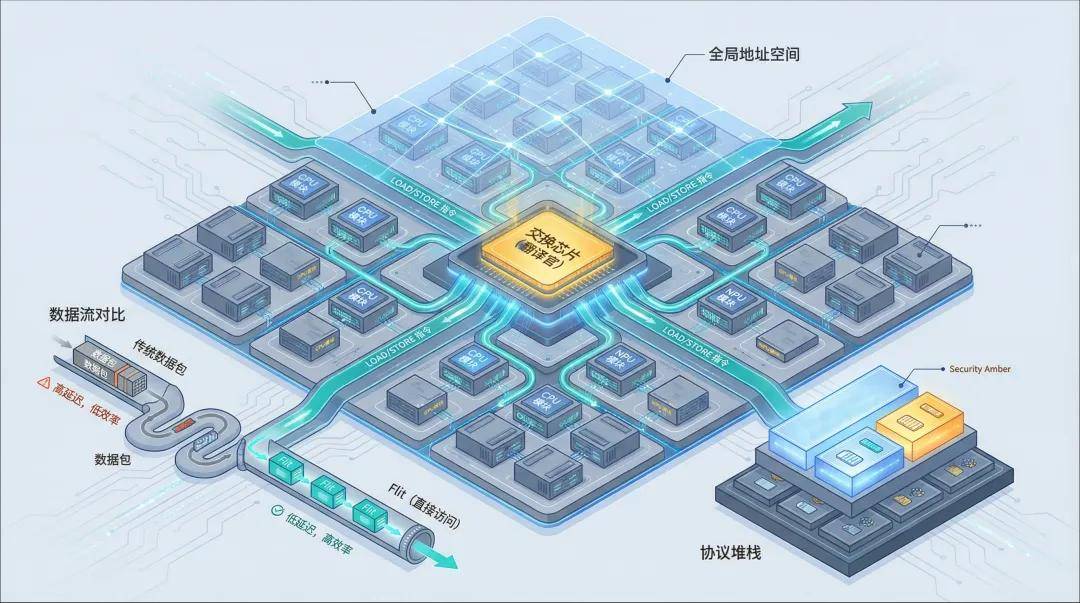

First, communication protocols and cache coherence.

The communication protocol no longer transmits bulky 'data packets' but rather 'Flits' containing memory addresses, operation codes (read/write), and cache state bits. At the same time, a cache coherence protocol is needed to broadcast coherence signals through the bus, ensuring that all computing units see the same information.

Second, a switching chip that acts as a 'translator.'

The switching chip plays the role of a 'translator,' enabling CPU, NPU/GPU, and other devices to interconnect under a unified protocol, integrating them into a single global address space. Regardless of where the data is stored, it has only one 'global address,' and CPUs, NPU/GPUs can directly access it through the address.

Most 'pseudo-super nodes' that fail to meet these conditions adopt a PCIe+RoCE protocol interconnection scheme, which is typically a case of 'big words grab attention, small words disclaim responsibility.'

RoCE cross-server memory access requires RDMA and does not support unified memory semantics or hardware-level cache coherence. It still relies on network cards, queues, and doorbell mechanisms to trigger transmission, essentially still 'sending a package,' just with a faster courier. Meanwhile, the theoretical bandwidth of PCIe per lane is 64GB/s, an order of magnitude lower than the bandwidth requirements of super nodes.

The result is that 'super nodes' are promoted without supporting unified memory addressing, failing to achieve global memory pooling and memory semantic access between AI processors. Clusters can only achieve 'board-level' memory sharing (e.g., intercommunication among eight cards in a single machine). Once outside the server node, all memory accesses must rely on message semantics communication, presenting obvious bottlenecks in optimization.

03 What Is the Value of Super Nodes? The Perfect 'Partner' for Large Models

Many may ask: What's the point of going to such great lengths to achieve 'unified memory addressing'? Is it just for technical 'purism'?

The conclusion is: Unified memory addressing is far from a 'mythical skill.' In the practical training and inference of large models, it has been proven to offer significant benefits.

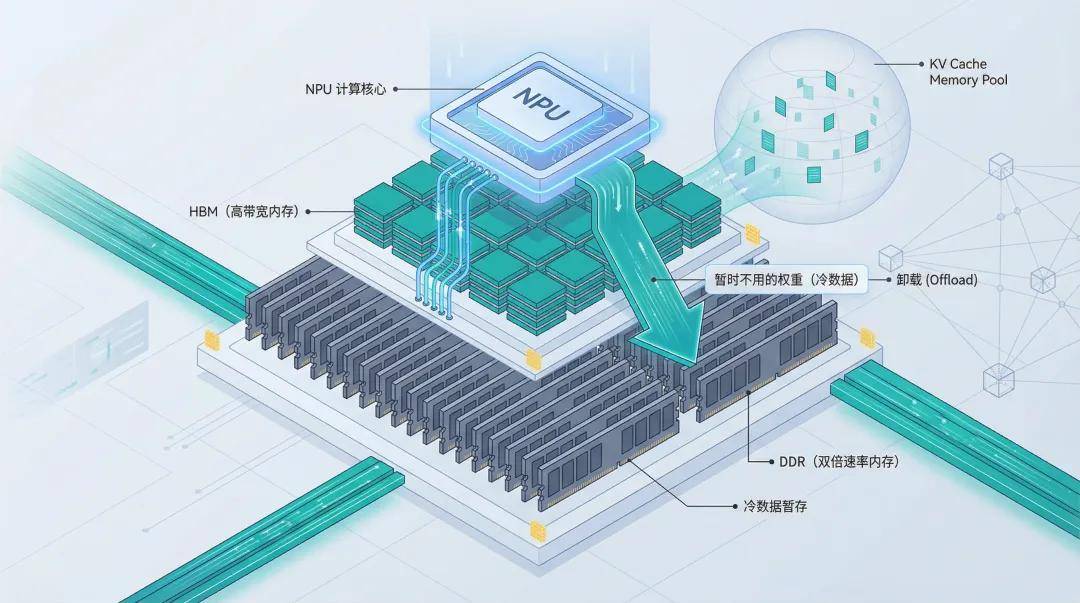

The first scenario is model training.

When training ultra-large models with trillion-parameter scales, HBM capacity often becomes the primary bottleneck. With 80GB of memory per card, there's little room left after loading model parameters and intermediate states.

When memory is insufficient, the traditional approach is to 'swap to CPU'—using PCIe to move data to the CPU's memory for temporary storage. However, there's a major issue: PCIe bandwidth is too low, and CPU involvement in copying is required. The time spent moving data back and forth exceeds the time spent on GPU computation, significantly slowing down training speed.

In a true super node architecture, the CPU's memory (DDR) and NPU's memory (HBM) are in the same address space, allowing for fine-grained memory management using a 'storage-replaces-computation' strategy: temporarily unused data or weights can be offloaded to the CPU's memory and quickly pulled back into on-chip memory for activation when needed through 'high bandwidth & low latency' capabilities, improving NPU utilization by over 10%.

The second scenario is model inference.

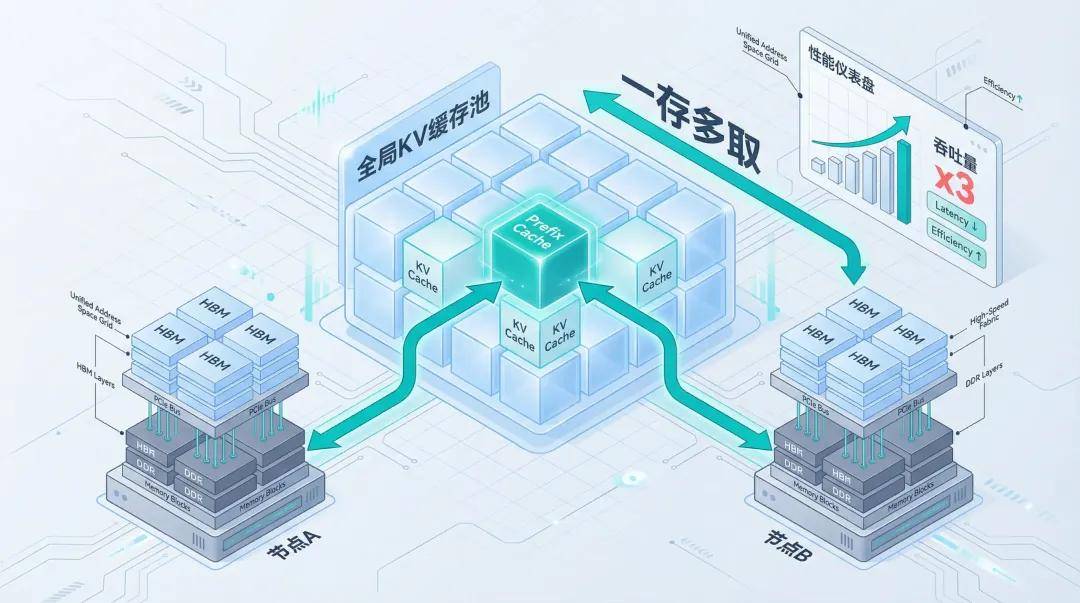

In multi-round dialogues, each round requires Put and Get operations, where Put stores KV data into the memory pool and Get retrieves it. Larger KV Cache spaces are needed for frequent data storage.

Traditional clusters typically bind KV Cache to the memory of a single card. If a user asks an excessively long question and Node A's memory is overwhelmed by KV Cache, nearby Node B cannot lend its unused memory without unified memory addressing, necessitating task rescheduling and recomputation.

With unified memory addressing, KV Cache can be globally pooled and support Prefix Cache reuse. For example, 'System Prompt' is usually fixed and only needs to be stored once in global memory, allowing all nodes to read it directly through a 'one-store, multiple-retrieve' approach. When the PreFix Cache hit rate reaches 100%, cluster throughput performance can improve by threefold.

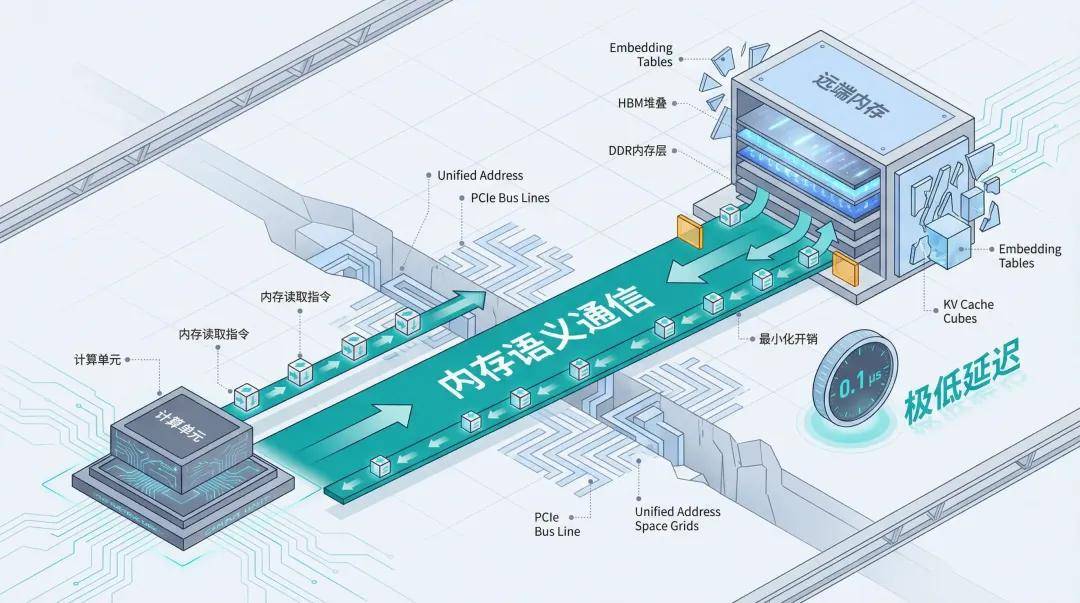

The third scenario is recommendation systems.

Search, advertising, and recommendations are the 'cash cows' of the internet, relying on ultra-large-scale Embedding tables. Since Embedding tables often exceed the memory capacity of a single machine, they must be fragmented and stored across different servers.

During inference, the model frequently needs to retrieve specific feature vectors from the Host side (CPU memory) or remote Device side. If small packets are handled using 'send a package' methods like RoCE, the overhead of packing and unpacking dominates, leading to severe doorbell effects and persistently high latency.

With unified memory addressing, combined with a hardware-level memory transfer engine, computing units can directly issue read instructions to remote memory, automatically handling data movement. While the first vector is still in transit, the second request can already be sent, significantly reducing communication latency and improving end-to-end recommendation efficiency, potentially achieving minimal overhead.

It's no exaggeration to say that the three capabilities of 'high bandwidth, low latency, and unified memory addressing' must work in synergy to truly enable clusters to function like a single computer, to achieve genuine super nodes, to be the perfect 'partner' for large model training and inference, and to represent the inevitable direction of evolution for computing infrastructure in the AGI era. Without the capability of 'unified memory addressing,' it's merely riding the wave of 'super nodes.'

04 In Conclusion

When we strip away the layers of disguise from 'super nodes,' we can see that the competition in AI infrastructure has shifted from mere hardware stacking to architectural competition.

The technical jargon "unified memory addressing" might seem arcane, but in certain respects, it's akin to a golden ticket ushering in the next era of computing paradigms. As a core capability for "One NPU/GPU," it tears down the barriers erected by physical servers, enabling the "essence" of thousands of chips to coalesce into a singular entity. Products that are mired in the outdated approach of "brute-force server stacking" will, in the end, be swept away by the relentless tide of Moore's Law's obsolescence.