Thousand-Yuan-Per-Unit Data Outsourcing: A Magnet for 985 Graduates

![]() 02/05 2026

02/05 2026

![]() 480

480

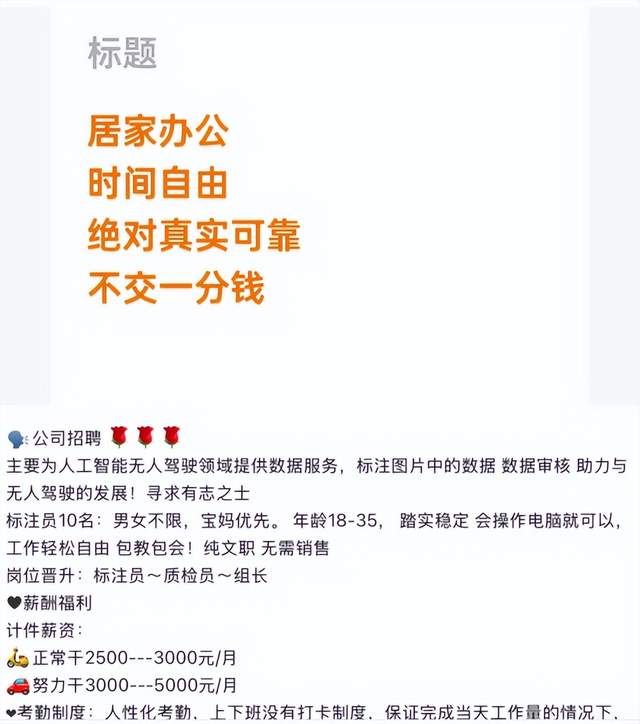

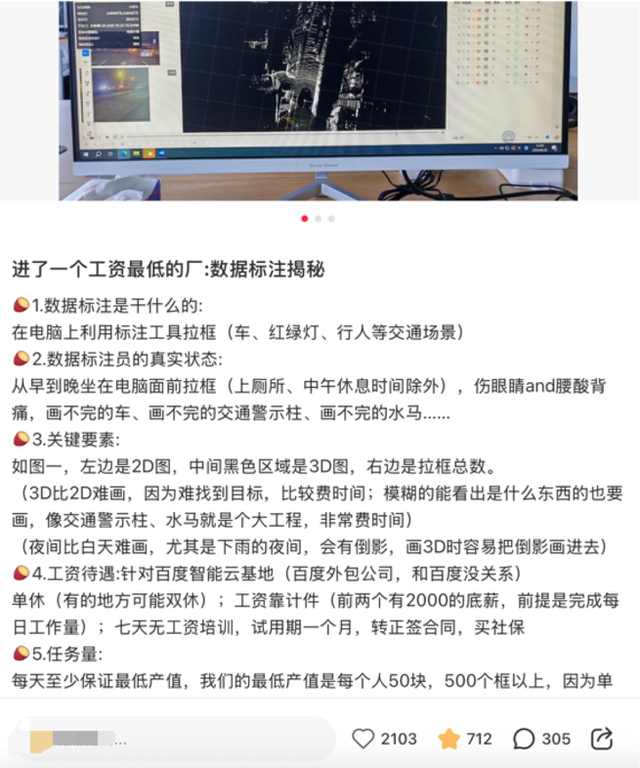

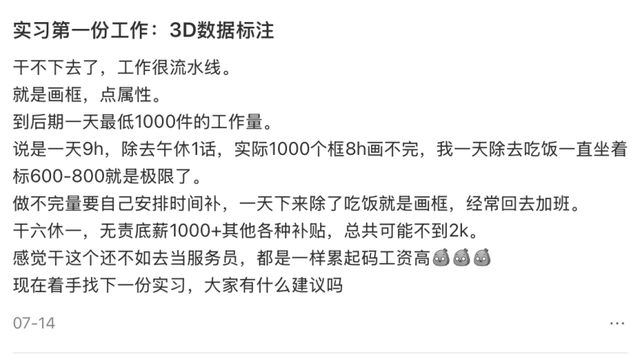

When the topic of data annotation arises, many still recall scenes from a few years back: In outsourcing hubs across second- and third-tier cities, hundreds of workers would sit in rows, eyes fixed on screens as they meticulously outlined vehicles, pedestrians, and traffic lights in images. These tasks, with their extremely low barriers to entry, required no prior training and compensated workers on a per-piece basis. Completing a thousand annotations would yield a meager 200 yuan.

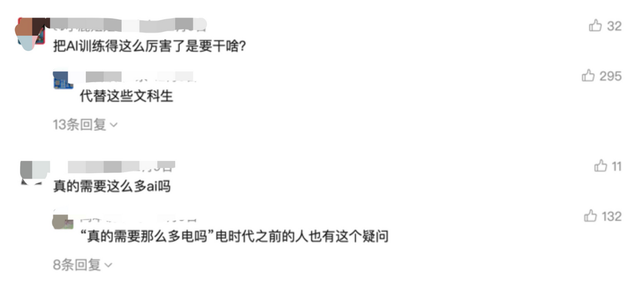

However, the landscape has subtly shifted in the past year or two. With the advancement of model capabilities, training now demands not just recognition skills but also judgment and reasoning abilities.

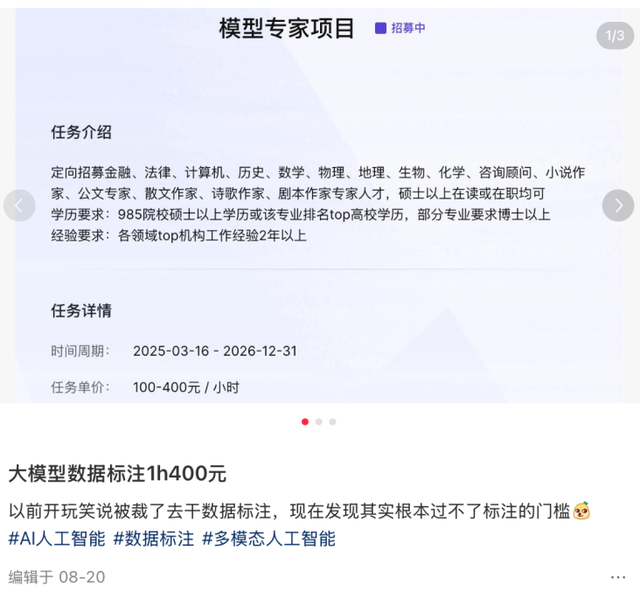

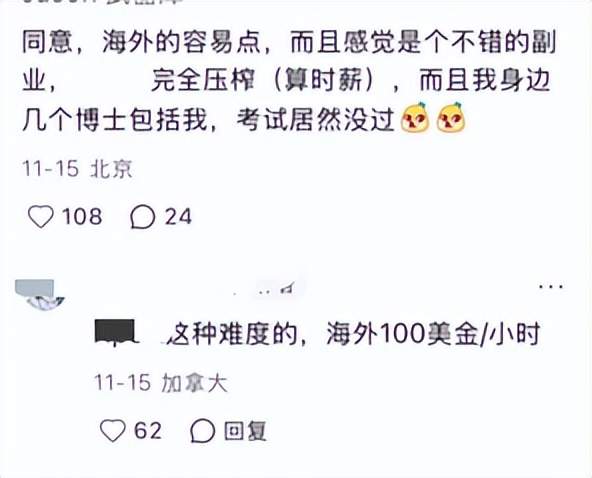

Consequently, a new breed of annotation tasks has emerged, boasting hourly rates exceeding a thousand yuan, and gaining traction on major platforms and crowdsourcing communities. These tasks include evaluating AI responses for hidden biases, refining misleading medical advice, and comparing the neutrality of two political topic responses.

These tasks, often spanning one to two hours, require annotators to possess linguistic sensitivity, common-sense reasoning skills, and even a basic understanding of legal or ethical principles. Compensation has also seen a significant uptick, with standard tasks starting at a hundred yuan. In more complex scenarios, earning 800 to 1000 yuan per task is not uncommon.

Why is one form of labor, essential for the operation of intelligent systems, highly sought after and well-compensated, while another is relegated to the bottom rung? What implications does the evolution of model annotation demands hold for the average worker?

The annotation of large models is not a novel concept. As early as around 2018, with the explosion of computer vision and speech recognition technologies, the data annotation wave swept into China's vast grassroots labor market. This included unemployed youth in third- and fourth-tier cities, stay-at-home mothers, college students seeking part-time work, and even some retired individuals looking to supplement their family income. Platforms subcontracted tasks through WeChat groups, part-time job apps, or local labor intermediaries, forming a digital gig economy network that spanned both urban and rural areas.

At that time, recruitment ads were straightforward: "Basic computer skills required," "Work from home," "Daily wage payment." The low barriers to entry meant that virtually anyone could participate, regardless of educational background or professional experience. As long as one could distinguish traffic lights, understand Mandarin, and accurately click a mouse, they were qualified to start working.

However, beneath this veneer of inclusivity lay a harsh reality known within the industry as cyber sweatshops.

To maintain the massive data supply required for model training, platforms typically set high production quotas. Skilled workers were expected to complete at least 500 image annotations per day, with compensation for qualified images ranging from a mere 0.2 to 0.4 yuan. Daily earnings rarely exceeded 200 yuan, often falling short of the price of a single question in knowledge-based crowdsourcing.

Here, labor was highly standardized, fragmented, and dehumanized. Even a week of sitting could cause noticeable dizziness and neck stiffness. There was little difference in skills, experience, or career prospects between working for a year and working for a day. Once platforms introduced AI pre-annotation tools, the demand for human labor rapidly diminished, leaving workers with no bargaining power and forced to accept wage cuts or elimination.

On the other end of the spectrum, a different form of data production was emerging. PhD students from prestigious 985 universities, attending physicians from top-tier hospitals, senior lawyers from law firms, and lead writers from financial media outlets... They sat in libraries, cafes, or home studies, spending two to three hours crafting a reference answer on topics such as "the impact of generative AI on medical diagnosis liability determination" or "how to explain monetary policy transmission mechanisms to high school students." Upon completion, their accounts were credited with 600, 800, or even 1000 yuan. They did not need to clock in, rush quantities, or accept tasks that did not align with their professional expertise. Platforms even actively sought their participation in high-level project evaluations.

Thus, while both groups provided training data for large models, labor was divided into two distinct worlds. On one side, there was mechanical clicking at 0.5 yuan per task, exchanging vision and youth for meager daily wages. On the other side, there was cognitive output worth over a thousand yuan per task, exchanging professional expertise for flexible and high compensation.

High-value tasks brought high income, high cognitive stimulation, and industry resources, forming a positive cycle. Low-value labor, on the other hand, was trapped in a negative spiral of low wages, lack of growth, and skill degradation.

This inevitably raised questions: Is AI becoming the culprit of polarization? What exactly lies behind these so-called high-paying annotations?

As the demand for general model capabilities shifted from recognition to reasoning, vertical models in fields such as medicine, law, and psychology rapidly developed. Simple annotations could no longer meet training needs. AI no longer needed people who knew the answers but those who could teach it how to reliably generate answers.

So, what was the talent profile for those who annotated these high-paying model annotations? And what kind of values did they embody?

On the surface, some individuals earned over a thousand yuan per task, enjoying work freedom and flexible hours, seemingly entering a new blue-collar class in the intelligent era. However, a closer look revealed that while the door was not explicitly labeled as exclusive to prestigious universities, it quietly tilted toward graduates of 985 and 211 universities in practice. Platforms may not solely rely on diplomas, but in the face of a vast number of applicants, educational qualifications served as the most efficient initial screening signal.

A PhD holder with years of research experience once attempted to participate in a large model project but was rejected during the trial annotation stage. His response was deemed "too academic and lacking in teaching guidance," failing to meet the platform's requirements for "AI-friendly expressions." This indicated that while educational qualifications served as a stepping stone, what truly determined retention was the ability to translate professional knowledge into a thinking paradigm that models could learn from.

Of course, a high level of education to some extent also meant higher compensation. In fields such as computer science, clinical medicine, law, or finance, a task that required integrating cutting-edge literature and constructing reasoning chains often commanded a price ranging from 600 to 1000 yuan. Even in liberal arts directions such as philosophy, education, and journalism, as long as there was critical depth or teaching value, hourly wages could easily exceed a hundred yuan. However, behind the high rewards lay stringent quality thresholds. Platforms did not pay for effort but for a one-time pass rate. Most tasks required two to three rounds of revisions, and a single logical oversight or citation deviation could result in the entire task being rejected.

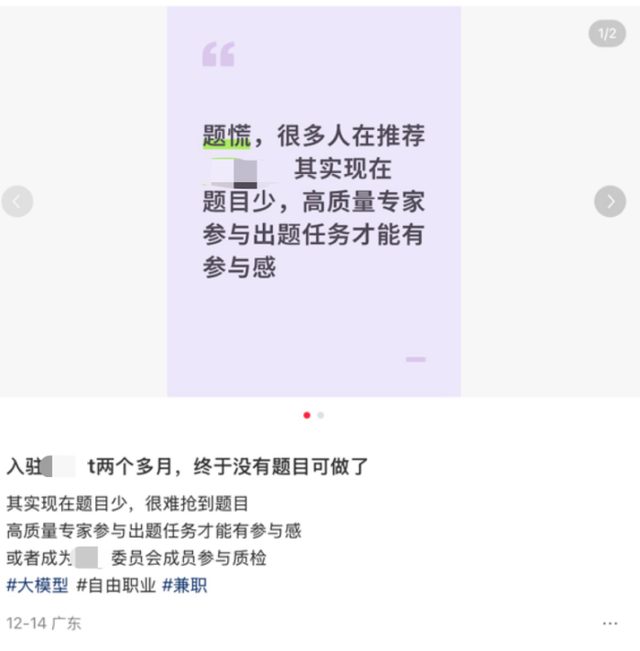

In terms of work format, platforms periodically released question banks for users to claim autonomously, with no clocking in, no fixed office hours, and the flexibility to work whenever available. This flexible work format attracted a large number of graduate students, young teachers, and freelancers. However, this did not mean that a one-time pass guaranteed lasting security. The system dynamically allocated task weights based on historical delivery quality. Those who performed exceptionally were labeled as "high-quality contributors" and were prioritized for high-priced questions, while those who required repeated revisions were quietly downgraded by the algorithm, resulting in fewer task allocations.

Ultimately, what was being purchased at over a hundred yuan per hour was not just time but high-quality human thinking that was scalable, standardizable, and could be internalized by AI. Therefore, this ticket to high wages was only issued to those who could both delve deeply into domain knowledge and step out of academic discourse to continuously iterate their expression methods—talents capable of human-machine collaboration.

However, AI's evolution never ceased; it continuously eliminated bottom-tier mechanical labor while raising the threshold for cognitive collaboration. Those who were writing question-answer pairs yesterday may need to design ethical test sets today; outputs considered expert-level today may be automatically synthesized by new models tomorrow.

In essence, AI was constantly generating new forms of work, and the nature of this process remained the "exploitation" of human physical and mental labor to fuel its own evolution.

AI's evolution has never ceased to spawn new roles. A decade ago, no one knew what a data annotator was; five years ago, prompt engineering was still an obscure term; today, "AI trainers," "ethics alignment specialists," and "multimodal content designers" are becoming hot recruitment terms.

But with each step forward, the division of human labor deepened. As models transitioned from recognizing images to generating legal opinions and writing medical diagnosis recommendations, their definition of "good data" also upgraded.

In other words, AI was constantly eliminating old positions and creating new ones in its evolution. When traditional data annotation first emerged, there were even tutoring agencies offering related training. But now, high-paying knowledge annotation had erected new skill barriers.

Firstly, the emergence of new positions did not imply equal opportunities. As data annotation upgraded, the entry barriers also rose. While platforms did not explicitly state "985 graduates only," they effectively barred the majority of non-systematically trained individuals through trial annotation tasks, professional background reviews, and delivery quality tracking.

Secondly, even for those who entered high-level annotation positions, the nature of labor relations remained unchanged. Most practitioners still existed in the form of "flexible employment" and "project outsourcing," without labor contracts, promotion paths, or even recognition as part of the company's formal human resources structure. They might spend hours each day judging whether AI-generated content "offends minority groups" but had never participated in the formulation of relevant ethical guidelines. Their mental labor was commandeered, yet their agency was erased.

What was alarming was that the AI industry was rationalizing this inequality through skill myths. Platforms often claimed that "high-value tasks should naturally match high-ability individuals," as if wage disparities were entirely determined by personal effort. In reality, the so-called high-level skills were often temporary, fragmented, and non-accumulative.

Today, you might be judging political biases; tomorrow, you might shift to medical terminology calibration; the next day, you might be asked to understand metaphors in science fiction novels. These tasks were disjointed and difficult to translate into transferable career assets. Workers were forced to continuously learn and adapt rapidly, yet they remained in a precarious state of being used and then discarded.

And once the model learned a certain judgment pattern through human feedback, such annotation tasks rapidly diminished or even disappeared. Those who were writing thousand-yuan question-answer pairs yesterday might find no similar tasks available tomorrow. You contributed the crucial data that made AI smarter, yet you could not share in any of the benefits after its commercialization.

Therefore, when we saw news of "200 yuan per task," perhaps we should not rush to celebrate the disappearance of low-end labor. What truly deserved observation was where those who were doing 0.5-yuan-per-task annotations had gone now.

The development of AI would not halt, and job roles would continue to evolve. However, for specific individuals, each upgrade might represent a narrow door that must be crossed.