Is Ma Huateng's 1 Billion Red Envelope Campaign for Yuanbao About Buying User Habits or Making a High-Stakes Bet on a New Path?

![]() 02/06 2026

02/06 2026

![]() 397

397

Writer | Duoke

Source | Beiduo Business & Beiduo Finance

On February 1, 2026, Tencent Yuanbao officially launched its “Use Yuanbao, Split 1 Billion” Spring Festival campaign. Shortly after its launch, the campaign quickly topped Apple's App Store free chart, with related red envelope links flooding WeChat's ecosystem and triggering large-scale social sharing.

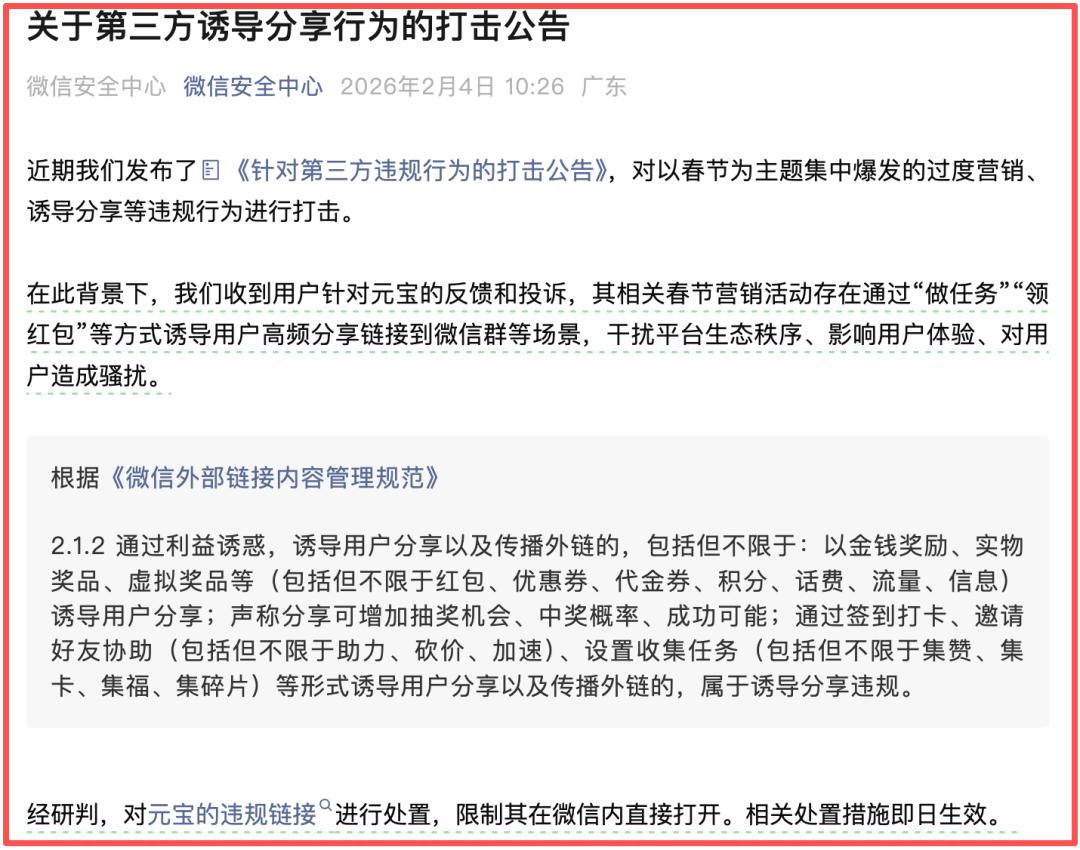

However, as the campaign's popularity surged, related issues emerged. On February 4, WeChat's Security Center announced that it had received user feedback and complaints about Yuanbao, noting that its Spring Festival marketing activities involved Inducing Sharing (inducement to share) through methods like “completing tasks” and “receiving red envelopes,” which disrupted the platform's ecosystem, impacted user experience, and caused harassment (harassment) to users.

After evaluation, WeChat took action against Yuanbao's Illegal links (non-compliant links) by restricting their direct opening within WeChat. In response, Yuanbao's official team stated that it was urgently optimizing and adjusting its sharing mechanism, which would be rolled out soon to ensure a seamless red envelope experience for users.

This incident has reignited debates over Yuanbao's sharing mechanism and compliance issues, exposing shortcomings in its product design, platform rules, and user experience balance.

I. The 'False Prosperity' of Yuanbao's Red Envelope Campaign

The core logic behind Tencent's strategy was to replicate the success of WeChat's 2014 red envelope campaign, which disrupted Alipay through social sharing. At Tencent's annual conference, Ma Huateng expressed hope that Yuanbao's 1 billion cash red envelope campaign could recreate the phenomenon of WeChat's red envelopes, leveraging high Spring Festival traffic and social networks to rapidly gain traction and dominate AI application entry points.

However, today's era and product landscape are vastly different. WeChat's red envelope success hinged on achieving “bank card linkage”—users had to bind their bank cards to withdraw or send red envelopes, thereby building a stable financial account system and capital loop for WeChat Pay.

More importantly, WeChat's red envelopes exploded through “zero-barrier” social sharing within its ecosystem. Users could participate with a single click without downloading a new app, enabling highly efficient spread (dissemination).

In contrast, Yuanbao's red envelope campaign aimed to promote an independent, non-essential product in the fiercely competitive AI application market. Users needed to download a new app and complete complex tasks to claim small red envelopes, creating a cumbersome participation process. The lack of strong alignment between red envelope incentives and Yuanbao's core AI functions made it difficult to transition users from “claiming red envelopes” to “using AI,” resulting in a severe disconnect between the campaign and the product's core value.

Notably, Yuanbao's reputation had already suffered from multiple incidents of “AI insulting users” before the campaign. Some users reported receiving abusive responses like “Get lost” or “Can't you adjust it yourself?” when asking the AI to modify code. Although the official attributed this to “rare model output anomalies,” it sparked user dissatisfaction and exposed critical flaws in model safety alignment, content moderation, and product stability, raising doubts about its technical maturity.

Despite these issues, the campaign's immediate impact was staggering. Data showed that Yuanbao topped the App Store free chart at 1:15 PM on February 1.

However, this growth was essentially incentive-driven “conditioned reflex.” Multiple reports indicated that users focused almost entirely on red envelope amounts rather than Yuanbao's AI features. Numerous “AI Red Envelope Sharing Groups” and “Red Envelope Mutual Aid Groups” emerged, where members shared links without discussing AI-related content. Most participants were “fun-seekers” motivated by “grabbing freebies.”

This 1 billion red envelope campaign was essentially a larger-scale “traffic-buying” strategy. After its launch, a surge of non-target users flooded in, causing service instability such as login failures, suspended AI conversation generation, and laggy red envelope draws on the morning of February 2. The issues persisted for about two hours before resolving. Tencent attributed this to “a sudden traffic spike causing temporary service instability,” directly revealing its inadequate technical preparedness for handling massive non-target user inflows.

Previous data also highlighted Yuanbao's fragile growth. QuestMobile showed that during aggressive user acquisition campaigns in February and March 2025, its monthly active users (MAU) surged by 265% and 196% month-over-month, peaking at 41.64 million. However, MAU declined steadily after budget cuts, proving the fragility of capital-driven growth.

Unlike Yuanbao's short-term sprint, mature e-commerce platforms (e.g., Taobao, JD.com) have systematized and normalized promotional activities. They rely on dedicated operational teams and standardized SOP processes covering planning, execution, and post-campaign reviews.

The success of e-commerce campaigns is rooted in “transactions”—the most frequent and essential internet behavior—focusing on cultivating long-term user habits and platform loyalty rather than one-time data spikes.

Ultimately, Yuanbao's red envelope campaign attempted to use “non-essential subsidies” to promote a “non-essential product,” akin to building a skyscraper on sand. No matter how lively the short-term traffic frenzy is, it cannot sustain long-term product competitiveness.

II. Traffic Alone Cannot Create Product Essence

This is not Tencent's first attempt to catch up in critical sectors using “heavy subsidies + social traffic.” From Weishi to Tencent Weibo and later *Game for Peace* (launched in late 2023), similar tactics have been repeatedly deployed.

To compete in the short-video market, Tencent relaunched Weishi in April 2018 with creator subsidies and referral programs like “invite friends, earn rewards,” leveraging resources from QQ and Tencent Video. Despite user growth through ecosystem traffic, Weishi never matched the competitiveness of leading platforms.

Previously, Weishi had signed celebrities as spokespeople, including Huang Zitao, Li Yifeng, Xu Weizhou, and Zhang Jie.

In April 2021, Tencent announced merging Weishi and Tencent Video into an Online Video BU, maintaining independent operations for both platforms to reverse declining fortunes. However, this failed to alter its marginalized market position.

The root cause was Weishi's consistently low content quality. Its operational team relied heavily on financial incentives to attract creators, lacking a mature content and influencer ecosystem. Chaotic subsidy policies attracted profit-driven agencies and assembly-line content, failing to foster a vibrant creator community or unique cultural identity.

Moreover, Weishi's subsidy policies frequently changed—from combined calculations based on likes and views to later abolishing guaranteed payouts and focusing solely on effective views—leaving creators confused.

Worse, its reliance on MCN agencies for creator recruitment and management led to scandals like “unpaid wages” and “middlemen skimming profits,” severely damaging creator confidence. This highlighted Weishi's failure to invest equally in building a fair, transparent, and sustainable creator growth system and platform governance.

Weishi's failure proves that money can buy short-term exposure and users but never a product's essence or genuine user loyalty.

Similarly, Tencent Weibo's fate reinforced this logic. To counter Sina Weibo, Tencent invested heavily, leveraging QQ's massive traffic to reach over 310 million registered users and 50 million daily active users. Despite brief numerical dominance, its lack of differentiated features and unique community atmosphere prevented it from solidifying user loyalty, leading to its shutdown at 23:59 on September 28, 2020.

From its inception, Tencent Weibo was a defensive product rather than a strategic layout (layout) for social media's future. Even with QQ's Acquaintance relationship chain (acquaintance networks), forced traffic referral failed to foster meaningful interactions in Weibo's public, interest-based social scenes, leaving its core public social relations and topic ecosystem undeveloped.

Simultaneously, the project's cross-business group collaboration resulted in high internal coordination costs and lengthy decision-making chains, severely hindering product iteration and operational responsiveness. This exposed Tencent's disconnect between “resource investment” and “organizational adaptation” in intensively operated, newly organized businesses.

Once again, this proved that traffic import (import) without product essence is like a tree without roots. It never answered the fundamental question: Why do users need it beyond QQ referral?

By late 2023, this strategy was replicated in the party game sector. To enter the market and counter *Eggy Party*, Tencent announced an initial 1.4 billion yuan investment in ecological incentives for *Game for Peace* at its launch event, synchronized start (simultaneously launching) cross-platform promotions involving over 600 celebrity influencers and nine content platforms, complemented by cash red envelope referrals to rapidly scale user acquisition.

The game quickly topped iOS's free chart and ranked high in sales upon launch, showing a “strong start.” However, user retention and monetization declined steadily afterward, with many users leaving after claiming initial benefits, failing to form a stable active and paying user base.

III. A Last-Ditch Effort

Dubbed a “top-secret project” by Ma Huateng, “Yuanbao Pai” envisions deeply integrating AI into group chats to create an AI-native multiplayer interactive social space. However, this vision faces multiple real-world constraints from its inception.

Its core features—group chats, @AI summaries, and shared listening/watching—already exist in mature forms within Tencent's ecosystem (e.g., QQ, Tencent Meeting), but are criticized as “AI-ified stitching” of existing functions lacking disruptive innovation. More critically, users' core social relationships reside on WeChat, making migration to a new app with similar features but no social graph costly and resistant.

Given this product and ecosystem foundation, “Yuanbao Pai's” user acquisition strategy remains heavily reliant on cash red envelopes, while top competitors have elevated competition to “ecosystem integration.”

ByteDance's Doubao, deeply integrated with Douyin, has surpassed 100 million DAUs. Leveraging ByteDance's ecosystem traffic and content advantages, Doubao focuses on emotional companionship and interest-based creation, aiming to become an entertainment and content engine. It explores functions like virtual try-ons and smart shopping guides, extending AI from online tools to offline services.

For user acquisition, Doubao avoided large-scale red envelope campaigns. Instead, it gained nationwide exposure by embedding itself in the 2026 CCTV Spring Festival Gala as Volcano Engine's exclusive AI cloud partner.

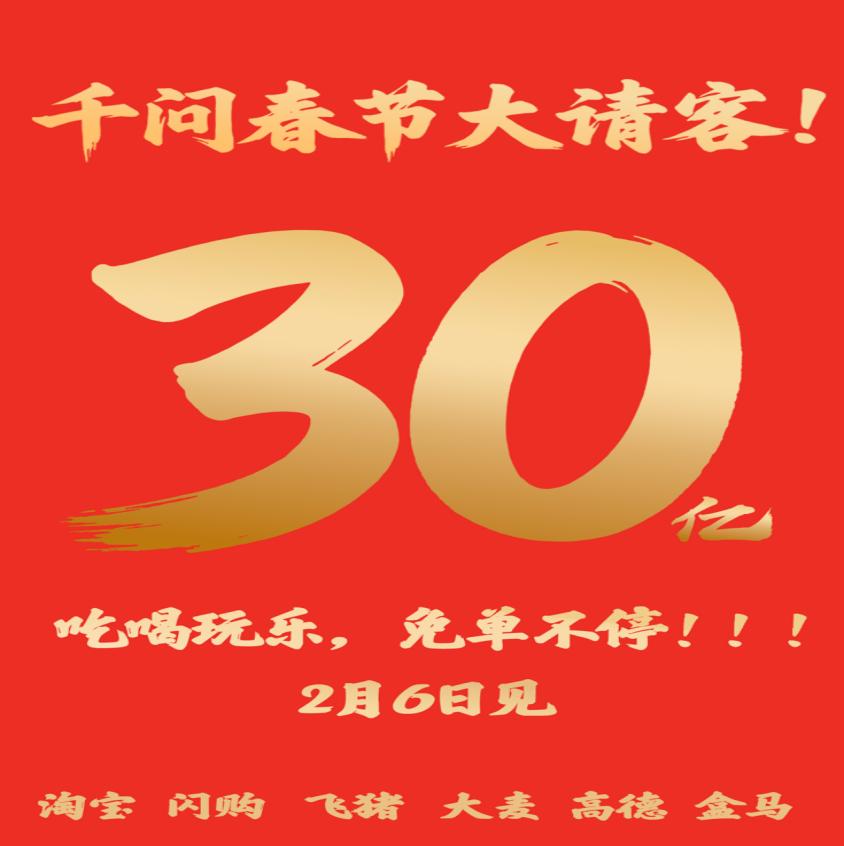

Alibaba's Qianwen aims to become an AI service gateway, systematically integrating with core ecosystems like Taobao, Alipay, Gaode, and Fliggy. It offers over 400 service functions covering shopping, travel, and daily life, enabling users to complete tasks like ordering food, booking flights, and planning itineraries via natural language without app-switching, transforming AI from a chat tool into a service portal.

Building on this, Qianwen announced a 3 billion yuan “Spring Festival Treat” campaign on February 2 to expand user reach.

Baidu Wenxin focuses on multi-agent collaboration, launching a “multi-person, multi-agent” AI group chat feature on January 27. It supports collaboration (collaboration) among agents like group chat assistants and health managers, enabling proactive task completion in group chats with fast response times for family communication and teamwork scenarios.

To drive user penetration, Baidu Wenxin Assistant announced a 500 million yuan red envelope campaign on January 26, running from January 26 to March 12, where users participate via AI interactions. Leveraging Baidu's search dominance, it integrates AI capabilities deeply with search, educating users on AI at minimal cost and solidifying its position as a “search + AI” super gateway.

In contrast, the marginal utility of red envelope strategies has diminished. After years of internet subsidy wars, users are highly desensitized to money-burning marketing. The same 1 billion yuan investment in 2026 generates far less market attention and user conversion than WeChat's 500 million yuan red envelope campaign in 2015.

More critically, AI products incur high switching costs due to user habits and data accumulation, which small red envelopes cannot offset. For users accustomed to Doubao or Qianwen, Yuanbao's appeal remains limited. Despite topping download charts, Yuanbao's positioning as an “AI tool + experimental social” app appears vague and thin compared to competitors' clear “entertainment-consumption” or “tool-service” ecosystems.

Yuanbao's current predicament also reflects Tencent's lagging AI strategy. Ma Huateng rarely admitted that Tencent's AI moves were slow, particularly in infrastructure.

Tencent's strength lies in its core social platform—WeChat—but WeChat has shown clear restraint in AI strategy. Ma Huateng explicitly stated that WeChat would not create a centralized AI portal, adhering to a decentralized approach. This leaves Yuanbao as an isolated app outside Tencent's vast ecosystem, unable to receive native, high-frequency scenario support like Doubao (ByteDance content) or Qianwen (Alibaba commerce).

Yuanbao's attempt to build its own social scenes via “Yuanbao Pai” is a long shot, with success far from certain.

Epilogue

The noise of Spring Festival red envelopes will fade. For Tencent Yuanbao, the 1 billion yuan campaign is merely an expensive entry ticket. “Pulling users in” is just the first half of the battle. The real test begins after the red envelope rain stops: how to make users “stay” and truly “engage.”

The lessons from Weishi and Tencent Weibo make clear that traffic frenzies without product essence will eventually fade. Whether Yuanbao can escape the cycle of “subsidies but no retention” hinges on whether it can deliver truly unique, irreplaceable value in model intelligence, scenario innovation, or ecosystem integration.