OpenAI Makes the Only Logical Choice: Becoming a Profit-Driven Company

![]() 12/30 2024

12/30 2024

![]() 554

554

Roughly 24 hours ago, OpenAI unveiled its comprehensive restructuring plan: it will establish a for-profit entity under which all commercial assets and personnel will operate. The original non-profit organization will transform into a shareholder and partner of the new profit-making company, focusing on AI-related ethical and social equity issues. Existing external investors, led by Microsoft, will all become shareholders of the new OpenAI for-profit entity. Rumors suggest that CEO Sam Altman will receive a 7% stake; given OpenAI's latest valuation of $157 billion, this could make him a billionaire (in USD) - although this claim has not been officially confirmed.

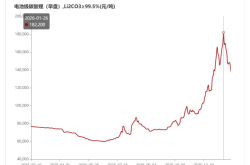

In December 2015, OpenAI was established as a non-profit organization with the mission to "develop safe and beneficial AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) for humanity." It accepted external investments in the form of "donations" rather than "equity." However, by 2019, this model became unsustainable as donations failed to raise sufficient funds. To accommodate Microsoft-led external investments, OpenAI revised its legal structure, resulting in a complex and confusing organizational framework with unclear power distribution:

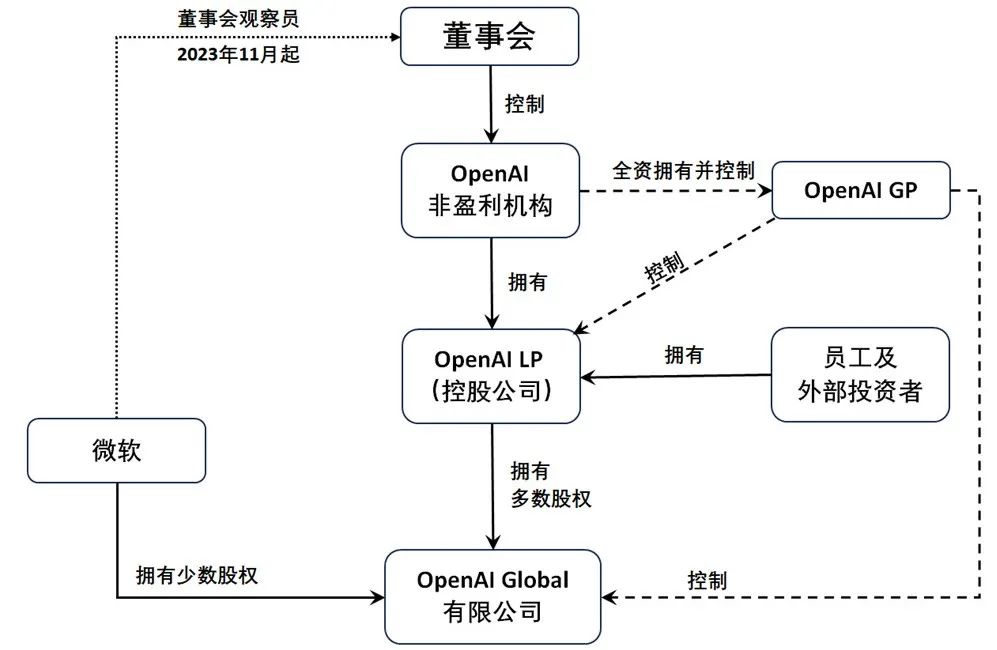

Under the original OpenAI non-profit, a for-profit holding company, OpenAI LP, was established, jointly owned by the non-profit, employees, and external investors. Actual business operations were managed by OpenAI Global Limited, which OpenAI LP held a majority stake in. While OpenAI LP owned a majority share in OpenAI Global (the actual operating entity), it lacked control; control rested with OpenAI GP, a company controlled by the OpenAI non-profit. OpenAI GP served as the "general partner" in a limited partnership, while OpenAI LP was the "limited partner" contributing funds but lacking control. Microsoft held a minority stake not in OpenAI LP but in OpenAI Global. This meant other investors indirectly held equity in OpenAI's operating entity, while Microsoft held it directly. Despite its unique position, Microsoft could not directly influence OpenAI's decisions (until November 2023, when this changed). OpenAI's ultimate decision-making power rested with its board of directors, essentially the decision-making entity of the non-profit organization. Notably, neither OpenAI LP nor OpenAI Global had their own boards and must obey the OpenAI non-profit.

OpenAI's corporate governance was not only complex but also permeated with a sense of "unequal power and responsibility": the board held all power and was theoretically unsupervised; employees and external investors could not influence board decisions nor those of the operating entity, which was entirely controlled by OpenAI GP and ultimately by the board. OpenAI believed this "four-unlike" structure allowed it to absorb external capital while remaining focused on its "core mission" - achieving safe and beneficial AGI for all humanity in the long term.

So, how was the board, which decided everything, composed? This is where it gets intriguing: Before July 2023, OpenAI had not publicly disclosed its board! The outside world could only learn through fragmented media reports that well-known entrepreneurs like Elon Musk and Reid Hoffman had served as directors before resigning. How the board was elected remains a mystery to this day. The official stance was only to disclose the board list, never discussing the nomination and election process, merely claiming that "a majority of board members should be independent, and independent directors should not hold any economic interests in OpenAI." Legally, since OpenAI was not a public company and had not solicited public investment, it was not obliged to disclose its corporate governance rules. Thus, all its decision-making processes remained shrouded in mystery.

After the "restructuring" in 2019, to accommodate external investors without changing its "non-profit" status, OpenAI established an extremely complex shareholder return model: Investors from the first round in 2019 could recover up to 100 times their initial investment, with profit caps gradually decreasing for subsequent rounds. For example, Microsoft's additional $10 billion investment in early 2023 had a profit cap of 10 times ($100 billion); before recovering the initial investment, Microsoft would receive 75% of OpenAI's profits, which would then decrease to 49% and eventually, after recovering 10 times the investment, Microsoft would relinquish all shareholdings. Most other investors had signed investment terms with "capped returns." Although these terms were obviously unfair, OpenAI's strong scarcity still attracted investors. Its valuation swelled to $86 billion in November 2023 and further to $157 billion by October 2024! Compared to investment returns, corporate governance was a more serious issue: Who decided OpenAI's future, and how were these decisions made? The outside world knew little about this. On the eve of the "palace coup" in November 2023, investors, including Microsoft, and most employees had neither influence nor prior knowledge of the OpenAI board. At that time, the board consisted of six members, three of whom were independent directors; it was these three, along with executive director Ilya Sutskever, who passed the decision to remove Sam Altman. Initially, Altman accepted his fate calmly, but within just three days, a dramatic turnaround occurred: The board could not find a suitable successor, and most OpenAI employees jointly petitioned to retain him, with Ilya, who initially participated in the coup, also switching sides. The intricacies of this struggle may remain a mystery for a long time. We can only speculate that the board's decision to remove Altman may have been related to his desire to restructure OpenAI as a profit-making company - more than a year later, he finally succeeded.

After thwarting the coup, Altman completely restructured the OpenAI board, with only one of the four directors who voted to remove him remaining (Adam D'Angelo). The new board was almost entirely composed of independent directors and augmented twice in March and June 2024, with Altman returning to the board through one of these augmentations. The new members were renowned in scientific, political, or financial fields, but the selection criteria and nomination/election processes were not publicly disclosed. We didn't even know if there was a formal "board election" process!

The biggest lesson from this chaos is that mixing non-profit and for-profit organizations has historically proven to be a breeding ground for corruption and infighting, and OpenAI was no exception. When OpenAI started, no one believed generative AI could quickly become profitable, but many were concerned about AI's ethical implications, so choosing a non-profit was understandable. However, as generative AI became profitable and OpenAI's valuation reached tens of billions of dollars, it was destined to abandon its past model - like forcing an adult to wear a child's clothes, either tearing the clothes or suffocating the adult.

In modern corporate governance, independent directors represent the interests of small and medium investors, protecting them from management and major shareholders. But whose interests do OpenAI's independent directors represent? According to OpenAI's original intent, they should represent "all humanity," overseeing whether AI development is safe and beneficial for humans. Once AGI is realized, they should ensure its fair and widespread use in society, excluding no one. While noble, this mission seems overly burdensome for OpenAI's independent directors. Assuming AI poses a real threat to humanity, can four businessmen, two scholars, and two former government officials on the current board really guard "the fate of all humanity"? This view is overly arrogant.

OpenAI's complete transformation into a profit-making company not only resolves governance issues but also aligns interests: Employees and investors can hold equity without "profit caps," more people can share in OpenAI's growth, and stakeholders have more opportunities to participate in decision-making. Non-profits will not be negatively affected but will receive substantial financial resources: they will become one of OpenAI's most important shareholders and can earn returns through share appreciation to fund AI ethics and social research. The main obstacle to this transformation was opposition from core employees, including Ilya, and early investors (donors) like Musk. The former have mostly resigned, while the latter's protests can be resolved with financial incentives.

History has shown that for profitable businesses, the modern joint-stock company is the most suitable organizational structure, underpinning the enduring success of "American capitalism." Shareholders elect the board through a shareholders' meeting, which in turn elects the CEO and governs the company. The management team, led by the CEO, is accountable to the board, directs employees, and advises on significant issues. Larger shareholders influence decisions by electing directors and CEOs; independent directors protect small and medium shareholders. This structure is not perfect but is the "least bad" among commercial models, upholding equal power and responsibility and separating governance from management.

For top-level companies - public companies - there's an additional layer of accountability: They raise funds through public offerings, issue shares and options as incentives, and use shares for investments and mergers; in exchange, they must disclose operational information to the market, accept regulatory scrutiny, and face multiple layers of supervision. Companies unwilling to bear such responsibilities can delist or establish governance clauses within legal frameworks, but these still require regulatory and shareholder approval. The ultimate goal is to maximize and balance stakeholder interests.

If shareholders' interests are not protected, they can respond in various ways: They can sell their shares, vote to influence or remove management, exert pressure through intermediaries and media, or take legal action. Despite shortcomings, the "shareholders-board-management" governance structure and shareholder-interest-centered performance evaluation model have proven effective. As we know, there's no perfect system; only systems that suit most scenarios and align with most people's interests exist.

OpenAI has finally made the necessary and only logical choice at this stage. Whether it maintains its leading position in generative AI and achieves stable profitability in the future is another question. Whether Altman violated business ethics during this process is another matter. Regardless, these questions do not affect the correctness of OpenAI's restructuring. The only regret may be that the restructuring came a bit late.