E-commerce in Turmoil: The Urgent Call to Revisit Retail's Core | Great Tide

![]() 12/09 2025

12/09 2025

![]() 490

490

Editor | Yang Xuran

In recent years, a prevailing sentiment has emerged within China's internet sector: traditional e-commerce has reached its zenith. This sentiment, to varying degrees, seems to resonate among major e-commerce behemoths. Consequently, to sustain growth in performance (retaining "performance" as pinyin for contextual integrity while translating the term within the sentence), these companies have generally opted to continuously diversify into new ventures—unfolding a tapestry of stories centered around food delivery and AI-driven e-commerce. However, amidst this pessimistic rhetoric, the fundamental value of the retailing industry appears somewhat overlooked. From a financial standpoint, retailing remains the cornerstone for these giants—be it Alibaba, with its substantial investments in AI, or JD.com, which has sacrificed profits for food delivery. Conversely, newer entrants like Xiaohongshu, ByteDance, and Kuaishou continue to pour resources into e-commerce, while even emerging AI platforms are eyeing the mature e-commerce landscape. Only Pinduoduo has taken a somewhat unconventional path by quietly retaining its profits. To a certain extent, the relationship between e-commerce platforms and e-commerce businesses now mirrors a besieged city. The physical ceiling on business penetration has driven those inside to seek new frontiers, exemplified by traditional e-commerce investments in AI. Yet, due to the vast market size, outsiders are eager to break in—especially content platforms and AI companies, which view e-commerce as a necessary and enticing avenue. The crux of the matter lies in the fact that the fundamental competitiveness of retailing has always been price. Regardless of how e-commerce platforms strategize for the future and pursue transformation, their customers remain primarily concerned with price and whether they can conveniently purchase high-quality, low-priced goods on the platform. Failing to meet this expectation risks abandonment by consumers before being overtaken by AI. Even as entities with hundreds of billions or trillions in scale, surviving the next wave of consolidation in the e-commerce industry remains an arduous challenge, akin to walking on thin ice. Maximizing long-term value is no easy feat. Companies like Suning and Gome once enjoyed immense success, but ultimately, their billions in profits proved fleeting.

Burning Money

To comprehend the various maneuvers by e-commerce platforms this year, we must first address a fundamental question:

Will there be a ceiling on the total scale of China's e-commerce market?

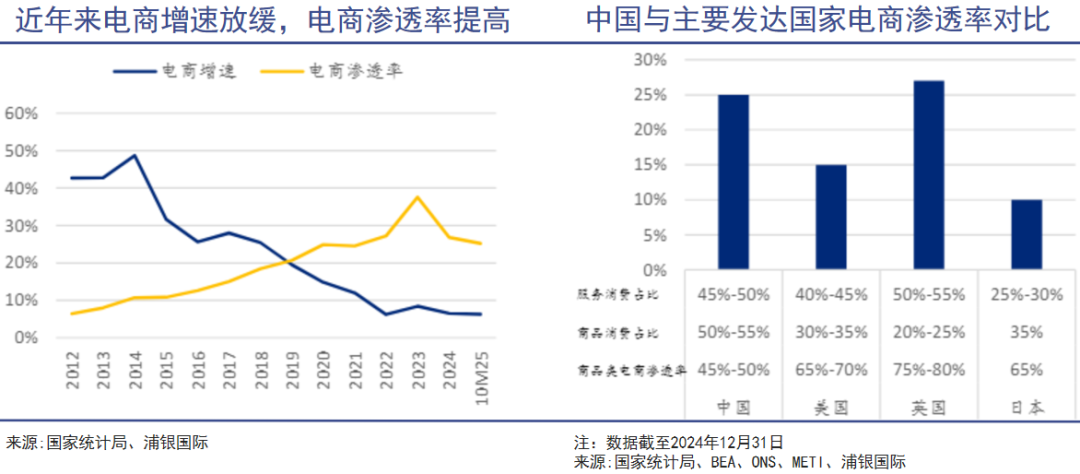

Data from the National Bureau of Statistics reveals that from January to October, online retail sales of physical goods in China grew by 6.3%, a significant slowdown compared to previous years, accounting for 25.2% of total retail sales of consumer goods. In international comparison, China's overall e-commerce penetration rate has reached 25%, significantly surpassing that of developed countries such as the United States and Japan.

The advantage of e-commerce primarily lies in the large-scale transactions of standardized goods. However, as an economy matures, the proportion of service-related expenditures (such as education, healthcare, tourism, and entertainment) in residents' consumption increases.

These service-related expenditures are challenging to "online-ize" and can only be consumed offline, reflecting the so-called local life services business in the internet economy. Therefore, the future competitive strategy of internet companies can no longer be a zero-sum game between online and offline but should foster deep integration between the two.

The essence of instant retailing is e-commerce business. With the resolution of the last-mile logistics issue, the boundaries between local life services and e-commerce have become increasingly blurred, making the competition among giants like JD.com timely and relevant.

In the traditional food delivery business, characterized by low profit margins and low technological content, a new battle has erupted, fueled by substantial financial investments.

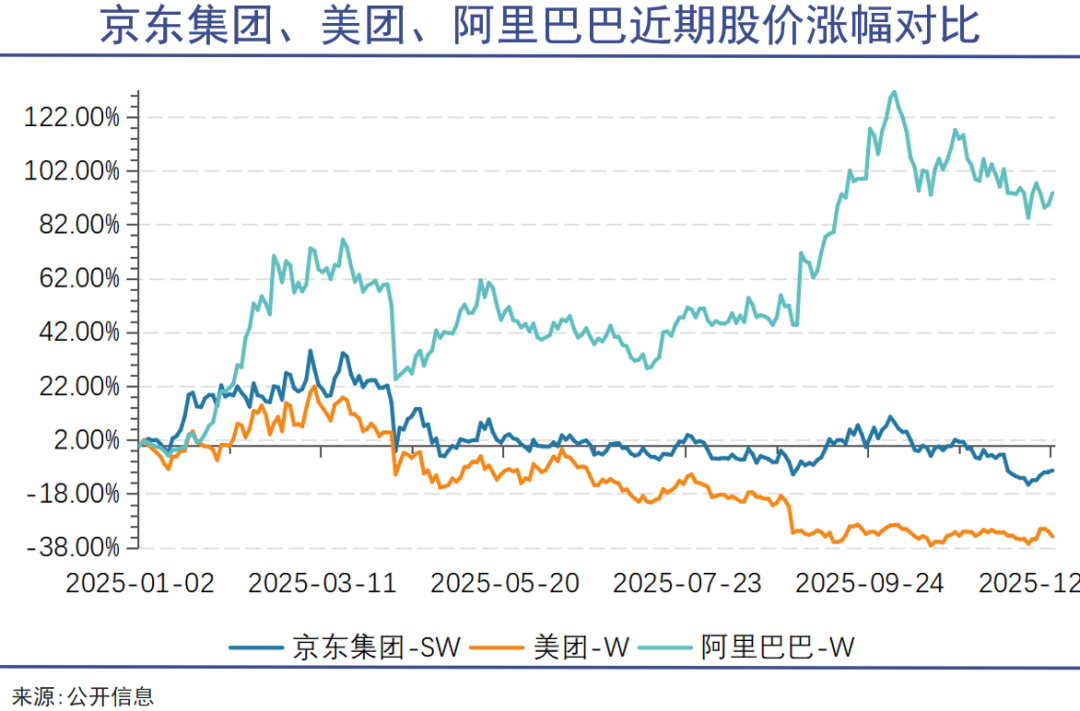

According to statistics, Alibaba, JD.com, and Meituan collectively spent 80 billion yuan on food delivery subsidies in the second and third quarters of this year. Capital markets have been skeptical of this expensive money-burning war from the outset, and concerns about stock prices were validated in the Q3 financial reports.

However, JD.com disclosed in its Q3 financial report that the conversion rate of its food delivery users to other businesses was close to 50%, explaining why it continues to invest in instant retailing despite short-term profit pressures.

Logistics resources and rider teams are pivotal for winning the future instant retailing battle. By injecting high-frequency food delivery orders into its logistics network, JD.com can fill delivery troughs, enhance the overall utilization of warehousing, trunk lines, and last-mile delivery capacity, thereby diluting costs and further bolstering the combat effectiveness of its rider team.

If JD.com refrains from this strategy, Meituan might pursue it even more aggressively from another direction. This is something Liu Qiangdong absolutely does not want to witness.

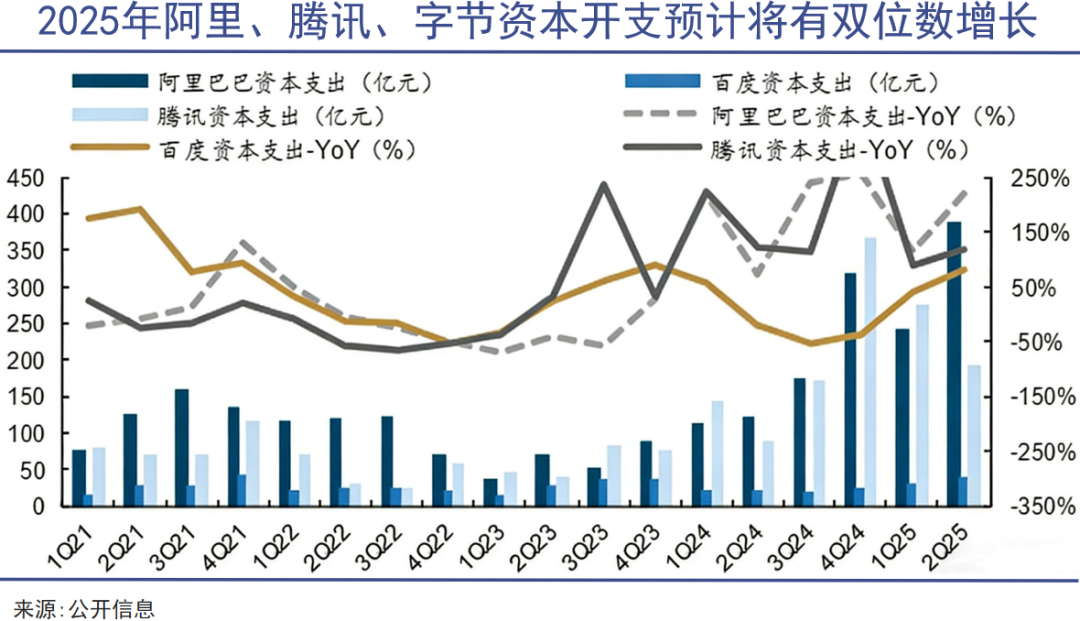

In contrast, Alibaba, the "e-commerce leader," harbors a more aggressive vision for its second growth curve. Its investment in food delivery is merely a few hundred billion yuan in disguised marketing expenses, while its investment in AI infrastructure is conservatively estimated at 380 billion yuan over three years, almost an all-in bet regardless of cost.

However, this relentless expansion of business boundaries also reflects the severity of growth anxiety in the entire e-commerce industry from another perspective.

Earnings

The new generation of internet companies that seem to be riding high—represented by content platforms like Douyin, Kuaishou, and Xiaohongshu—also harbor definite anxieties about growth. They have chosen to launch simultaneous offensives on e-commerce and AI businesses.

The anxiety of content platforms stems not only from the need for growth but also from the limitations of their business models. After all, the current model of pure reliance on advertising for monetization, while having high profit margins, also has a relatively obvious ceiling.

As the most important "traffic intermediaries," content platforms generate advertising revenue by essentially selling users' attention to advertisers such as e-commerce platforms and brands. This is a typical cyclical industry, where budget sizes are directly related to businesses' operating confidence and profit levels. During economic downturns, advertising budgets are often the first to be cut.

In contrast, commission income generated from e-commerce transactions is linked to more fundamental consumer demand. While it can also be affected by the economy, its volatility is relatively smaller than that of businesses' discretionary advertising budgets.

By building a closed-loop e-commerce ecosystem, content platforms can convert their internal traffic circulation into internal business circulation, profiting multiple times and at different levels from a single transaction—including commissions, payment fees, logistics services, merchant SaaS tools, etc. This allows them to deeply mine the value of individual users and break through the ceiling of per capita advertising revenue.

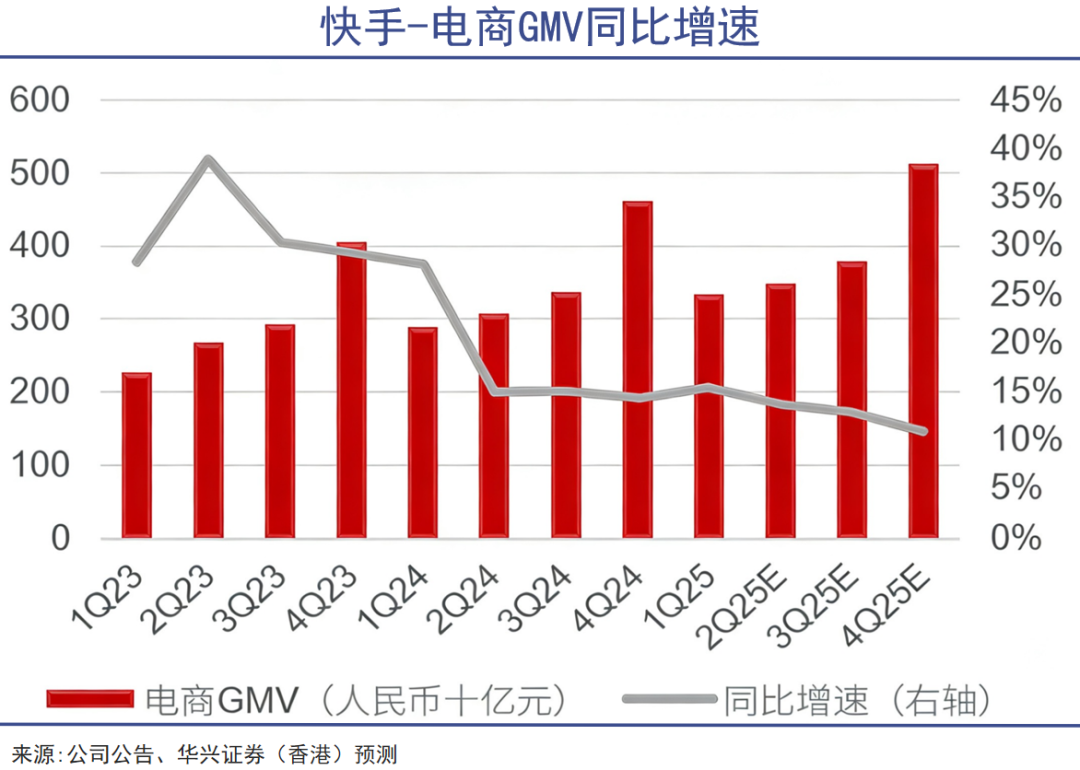

The data from Kuaishou's Q3 financial report is quite telling. In this quarter, Kuaishou's total revenue increased by 14.2% year-on-year to 35.6 billion yuan, with e-commerce business being the key driver of its core commercial revenue growth at an even faster rate (19.2%).

The recent launch of OpenAI's instant checkout feature further proves that e-commerce, or real commodity transactions, remains the most core and deterministic profit model in the internet world.

As a typical AI company, OpenAI has long coveted the e-commerce business. In April this year, it introduced product recommendation features in ChatGPT but still required users to jump to external platforms for purchases. By September, it officially launched the instant checkout feature, relying on partners like Etsy, Shopify, and Walmart for fulfillment.

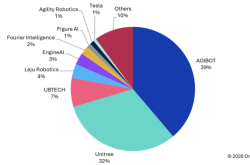

Although e-commerce is still in its infancy for OpenAI, considering ChatGPT's 700 million weekly active users and 75.6 million commodity-related conversations, AI companies' capabilities in e-commerce are not to be underestimated. Moreover, capital markets are bound to be eager to respond positively to all related changes.

The current industry consensus is that the degree of AI integration has become a critical variable determining long-term competitive trends. It is not just a tool for improving operational efficiency but also a fundamental force for reconstructing the "people-goods-place" ecosystem.

The current strategic moves by e-commerce platforms and content platforms indicate their desire to enter the next cycle by stepping on the bodies of their competitors, rather than just being used as tools.

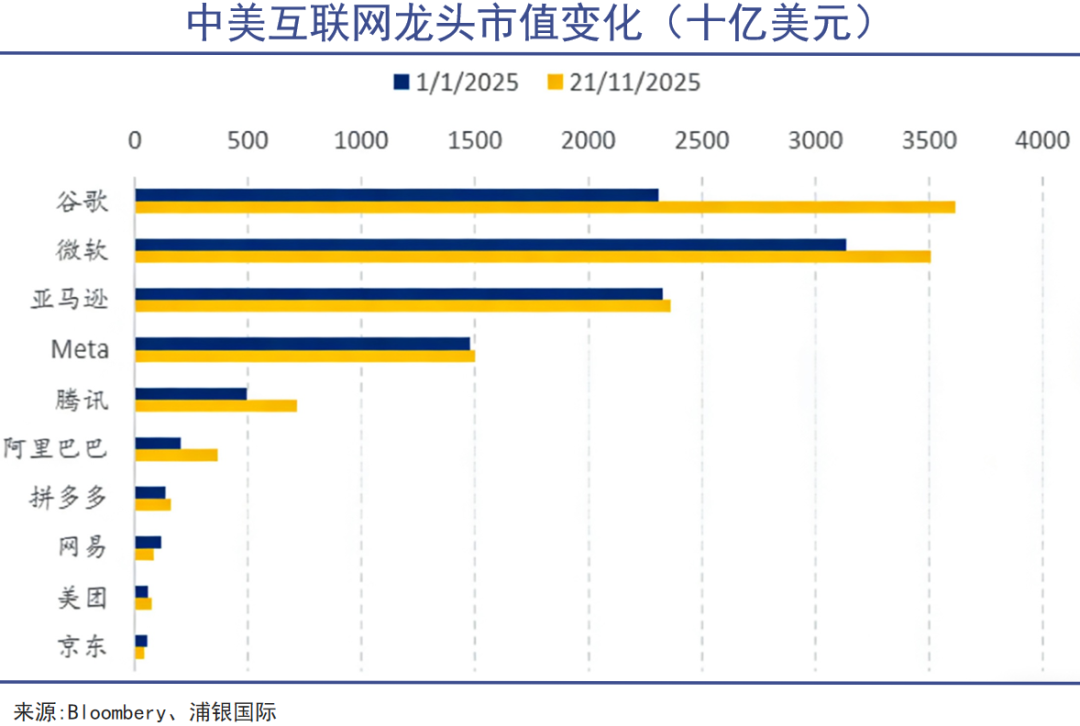

Therefore, the fiercest and most targeted competition against Alibaba is currently coming from ByteDance, not Tencent.

In terms of e-commerce business, Douyin E-commerce's GMV has surpassed 4 trillion yuan, directly squeezing Taobao and Tmall's market share (Taobao and Tmall's GMV is around 8 trillion yuan). In terms of AI entry points, Doubao and Qianwen Apps are vying for the top spot in domestic AI applications. Even when Alibaba just launched the Kuake Glasses, ByteDance quickly launched the Doubao Phone.

With ByteDance's valuation surpassing Alibaba's to reach 480 billion US dollars, the competition between the two giants in the AI e-commerce arena will only intensify and become more genuine.

Returning to the Essence

AI e-commerce: Is the focus on AI or e-commerce? That is the question.

Similarly, when the traffic dividend peaks and the market enters a phase of consolidation (translated in context to convey the idea of a mature market with limited growth opportunities), a fundamental strategic question will be placed before all internet companies: Should they position themselves as technology companies constantly pursuing growth, or should they return to the commercial essence and define themselves more certainly as retail enterprises?

In the past, internet companies were keen on telling technology stories and excelled at using high-investment, high-risk models to seek abnormal returns (translated in context to convey the idea of seeking disproportionate rewards) and a winner-takes-all outcome. Whether it was the money-burning subsidy wars that defined the early industry landscape or the current arms race for AI large models, both reflect this logic.

However, during economic downturns, high investments do not necessarily bring high returns but are likely to bring high risks. This has already been reflected in the giants actively competing in the food delivery business.

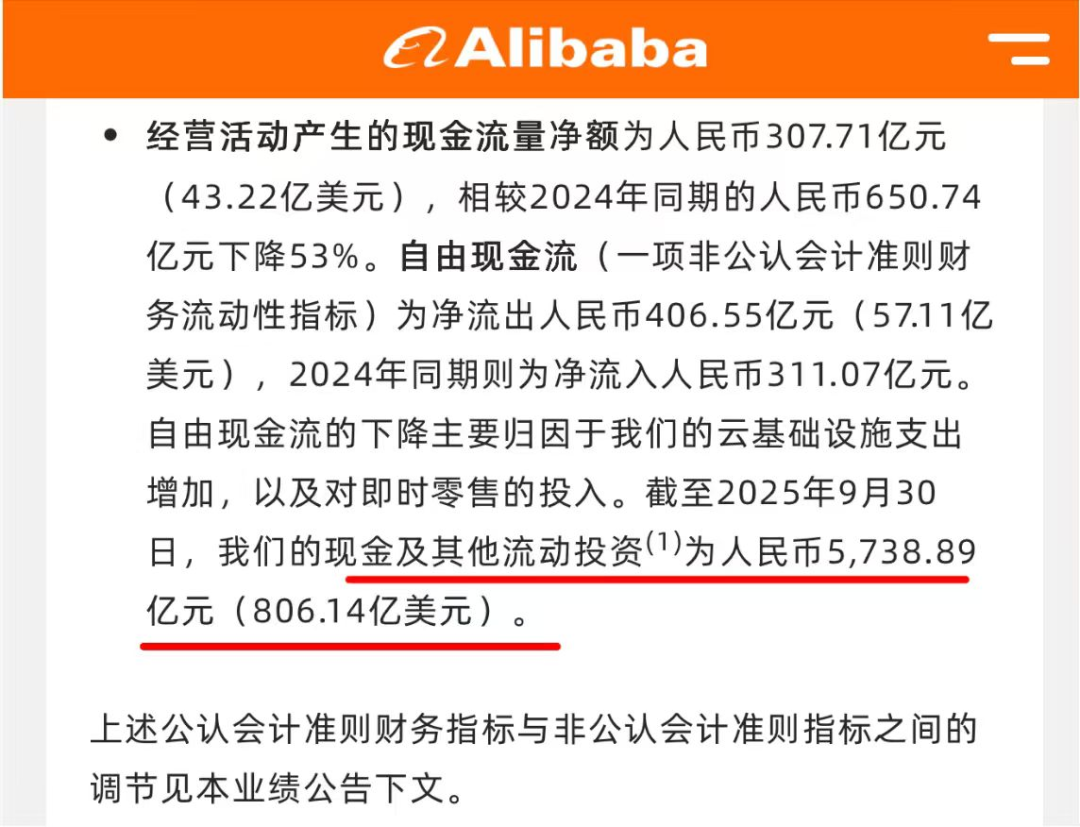

As of the end of September 2025, JD.com's total cash and short-term investments amounted to 198.272 billion yuan. Alibaba remains the "cash king," with total cash and other liquid investments of 573.889 billion yuan, still ranking first in terms of industry cash flow. Meituan's situation is more severe, as intense competition has led to a rapid cash burn rate.

Compared to these Chinese e-commerce companies in fierce competition, standard retail giants appear much more stable.

Retail companies typically have low gross profit margins and must rely on huge sales volumes and extremely fast inventory turnover to generate profits, requiring abundant working capital support. Moreover, during economic downturns, having sufficient cash means they can pay suppliers in advance to secure larger discounts and supply chain power.

Walmart, the retail king, is globally recognized as a master of cash management. Its classic indicator, the cash conversion cycle, is perennially (translated in context to convey the idea of consistent negative cycles) negative, meaning Walmart only needs to pay suppliers after selling goods and receiving customer payments. This cash strength ensures Walmart can withstand long-term low-price competition and squeeze its competitors' profit margins.

The low-price strategy is the foundation of the retailing industry's survival. Over the years, Walmart has never seemed to involve itself in concepts like new retailing or artificial intelligence but has focused all its resources on building sustainable low-price capabilities. After all, the appeal of high-quality, low-priced goods to consumers never goes out of style.

Therefore, ensuring high-quality, low-priced goods on the supply side is the most critical fundamental skill for retail enterprises. In this regard, companies backed by China's manufacturing base generally have a more stable foundation. The vast number of manufacturing enterprises and industrial belts specializing in specific goods are the most crucial foundations for these large domestic and foreign channels.

The emphasis on the supply chain and the extreme insistence on cost-effectiveness may not be as glamorous as billion-dollar investments in AI or hundred-billion-dollar investments in instant retailing, but they align with the consistent logic of the retailing industry throughout its long history:

Companies can seize new scenarios through rapid transformations, but ultimately, they must return to the industry's essence to achieve truly long-term revenue and value.