What Is the 'Depth Camera' Referenced in Autonomous Driving?

![]() 12/12 2025

12/12 2025

![]() 424

424

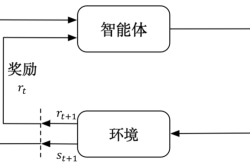

The realization of autonomous driving hinges on the support of diverse sensors. Among these, the pure vision approach has emerged as a popular choice in many technical frameworks. Nevertheless, since conventional cameras are incapable of perceiving depth information in the environment, certain technical frameworks incorporate the technology of 'depth cameras.' A depth camera denotes sensors that, in addition to capturing color (RGB), can directly or indirectly furnish information regarding the 'distance from each pixel to the camera.' In simpler terms, while an ordinary camera informs you about 'the apparent color and texture of a pixel,' a depth camera also reveals 'the distance of that point from the vehicle.' Precisely because distance information holds greater significance than color information in autonomous driving—vehicles must ascertain whether collisions are imminent, determine braking times, and devise path plans—all these tasks hinge on depth information or three-dimensional perception results fused with data from other sensors.

Three Common Operating Principles of Depth Cameras

Depth cameras come in various forms. Common types encompass stereo cameras (based on dual lenses), cameras that project structured or coded light, and Time-of-Flight (ToF) cameras. The depth representations they produce typically manifest as a 'depth map' or sparse point cloud. These serve similar purposes to the point clouds generated by LiDAR but differ substantially in terms of principle, accuracy, cost, and applicable scenarios.

1) Stereo Vision (Stereo)

The concept behind stereo vision is to emulate human eyes. Two identical color or black-and-white cameras are mounted side by side with a fixed 'baseline' (the distance separating the centers of the two lenses). When viewing the same scene, the same object point in the images will exhibit a horizontal position difference, known as disparity. Utilizing the known baseline length and the camera's intrinsic and extrinsic parameters, the disparity can be inversely calculated to determine depth (distance).

The crux of the stereo method lies in 'matching,' where the algorithm must accurately locate corresponding points for the same pixel in the left and right images. Scenes that pose challenges for matching include textureless surfaces, repetitive textures, highly reflective areas, or occluded regions. The advantage of stereo vision is that it can be implemented using ordinary camera hardware, offering a low-cost solution with high pixel counts. Theoretically, resolution and range can be enhanced by increasing the baseline and using higher-resolution cameras. However, its drawbacks include sensitivity to lighting conditions, textures, and computational resources, as well as a rapid decline in depth accuracy over long distances.

2) Structured Light and Coded Light

These methods involve projecting known optical patterns (such as stripes, dot matrices, or other coded graphics) into the scene and then using a camera to observe the deformation of these patterns on the object's surface, from which depth is inferred. Structured light is widely utilized in close-range applications, such as human body modeling and facial recognition devices (early structured light facial recognizers). Its advantages include high accuracy at close range and reduced reliance on texture, as the system provides its own 'texture.' However, its drawbacks include sensitivity to ambient light; under strong sunlight, the projected patterns can be overwhelmed, leading to depth measurement failures. Structured light is only suitable for short-to-medium-range applications (a few centimeters to a few meters). Extending its range to the tens of meters required for driving scenarios poses challenges related to power, visibility, and safety.

3) Time-of-Flight (ToF)

ToF cameras determine distance by measuring the time it takes for light to travel from the sensor to the object, reflect, and return to the sensor. Common implementations include pulsed ToF and phase ToF. Pulsed ToF directly measures the round-trip time of a pulse, operating on a straightforward principle but necessitating high-speed electronics. Phase ToF emits a continuously modulated light signal and measures the phase difference between the emitted and received signals to estimate distance, a method more commonly employed at short to medium ranges.

The advantages of ToF include the ability to directly acquire depth information for each pixel, excellent real-time performance, and lower algorithmic complexity compared to stereo matching. Its disadvantages encompass multipath interference (misreadings caused by multiple reflections of light in the scene), sensitivity to strong light (sunlight contains a significant amount of infrared light, increasing noise), and limited range and resolution. Industrial-grade ToF can achieve ranges of several tens of meters, but in automotive applications, achieving a balance between resolution, frame rate, and sunlight resistance still necessitates engineering compromises.

In addition to these three methods, hybrid schemes and solid-state 'flash' ranging devices that are closer in nature to LiDAR also exist. However, methods that rely solely on a monocular RGB camera for 'depth estimation' (learning-based monocular depth estimation) are not strictly depth cameras but rather techniques that infer depth algorithmically from a single image. Such depth estimations are usually relative, with scale uncertainty or requiring additional constraints for calibration, rendering them only a supplement rather than a reliable primary depth source.

Key Distinctions Between Depth Cameras and Ordinary Cameras

Ordinary cameras output brightness and color information, specifically the RGB values for each pixel. Depth cameras, in addition to these (and sometimes capable of outputting RGB as well), provide distance information from the camera. Depth data directly offers three-dimensional geometric information, simplifying subsequent detection, tracking, obstacle avoidance, and localization tasks. Ordinary cameras rely on visual algorithms (such as feature matching, structure from motion, or monocular depth estimation) to indirectly obtain distance information.

The design of ordinary cameras prioritizes high-resolution, wide dynamic range, and low-noise image acquisition, with sensors primarily recording photon counts. Depth camera hardware necessitates additional design considerations, such as light sources (for structured light, ToF) or dual-camera synchronization and high-precision clocks (for ToF), as well as stricter mechanical installation precision in some systems (stereo requires precise baseline and calibration). This implies that depth cameras often consume more power, are more complex, and are costlier than ordinary cameras, although stereo systems based on two ordinary cameras can offer cost advantages but place higher demands on computation and calibration.

Depth maps typically consist of single-channel floating-point or integer distance data that need to be converted into three-dimensional point clouds or utilized in subsequent perception modules with camera intrinsic parameters. Data from ordinary cameras is more suitable for direct input into visual networks for object detection, semantic segmentation, etc. Depth data and RGB data each possess their strengths; RGB excels at identifying categories and appearances, while depth excels at providing geometric information. Therefore, in autonomous driving systems, it is common practice to fuse the two, employing RGB for recognition and depth for localization and geometric reasoning.

Additionally, stereo vision may fail in low-light or textureless conditions; structured light can be overwhelmed by strong light; and ToF noise increases under direct sunlight or in the presence of strong infrared sources. Ordinary cameras also encounter challenges in high-dynamic-range scenes but can be improved through exposure control, HDR, and other techniques. Ultimately, different sensors have their blind spots in various environments, which is why autonomous driving systems employ multi-sensor fusion involving cameras, radar, and LiDAR.

What Are the Drawbacks of Depth Cameras?

Since depth cameras enable machines to directly perceive the three-dimensional world, many assume they can directly replace LiDAR. However, this is not the case. While depth cameras offer numerous benefits, such as stereo perception, precise ranging, and three-dimensional modeling, they also exhibit several shortcomings, particularly in complex automotive scenarios where various 'compromises' and 'trade-offs' are necessary.

One typical issue is the conflict between distance and accuracy. Stereo vision relies on the 'disparity' principle, which calculates depth based on the angular difference between two cameras viewing the same object. The challenge arises when objects are farther away, as the angular difference diminishes, leading to more significant calculation errors. To achieve accurate measurements at long distances, the distance between the two cameras must be increased, or the image resolution must be enhanced. However, increasing the baseline is constrained by installation limitations and the risk of occlusion, while higher resolution escalates computational burden and cost. ToF cameras perform well at close range but require more complex light sources and receivers to achieve long-distance, high-clarity measurements, driving up power consumption, heat, and cost. Structured light is nearly ineffective in automotive environments with strong light and long distances, being more suitable for short-range applications.

Another issue pertains to ambient light and object surface properties. Regardless of the principle, depth cameras fundamentally rely on light reflection. Real-world lighting conditions are far more complex than in laboratory settings. Strong sunlight can overwhelm signals, snow reflections can 'blind' sensors, and metallic surfaces, glass, and wet or slippery roads can all produce chaotic measurement results. ToF cameras may be interfered with by multiply reflected light, leading to incorrect distance calculations; structured light can deform on transparent or mirror-like objects; and stereo cameras struggle to find corresponding points in large textureless areas, such as smooth car doors or sunroofs. Not to mention rain, snow, fog, and nighttime lighting conditions, all of which pose challenges for depth cameras.

The resolution of depth maps is another persistent concern. Many automotive depth cameras output relatively 'rough' depth maps with sparse points and significant noise. Compared to clear RGB images, depth maps often lack detail, causing problems in identifying small objects or complex edges. Although algorithmic completion or combining depth and RGB data can enhance results, this also consumes more computational resources.

Stereo vision demands substantial computation for image matching, especially at high resolutions and frame rates, placing significant pressure on processors. While ToF cameras directly output depth information, cleaning up the results involves multi-frequency signal decoding, noise filtering, and multipath correction, all of which are resource-intensive. Given the limited computational power and energy constraints in automotive systems, a balance must be struck between accuracy, frame rate, and real-time performance.

Another practical issue is calibration and stability. Depth cameras are particularly 'delicate,' especially stereo vision systems. Even slight deviations in the angle or position of the two cameras can lead to inaccurate depth measurements. Vehicle vibrations, temperature changes, and minor collisions during driving can all affect calibration results. ToF cameras are also susceptible to temperature drift and require temperature compensation to maintain data accuracy. To ensure precision, robust mounting brackets, regular calibration, and even real-time algorithmic calibration are necessary.

Furthermore, depth cameras have a natural limitation: they can only 'see' what is directly in front of them. Occluded objects are entirely invisible to them. For example, low obstacles beside the vehicle or pedestrians in corners are undetectable by depth cameras if obscured, which is why autonomous driving technology never relies solely on depth cameras. They serve more as an auxiliary perception tool to fill gaps left by other sensors.

Theoretically, stereo cameras can achieve depth perception using two ordinary lenses, which seems cost-effective. However, integrating them into a vehicle complicates matters. Considerations include dust resistance, waterproofing, shock resistance, as well as passing automotive-grade certifications, EMC testing, and thermal design verification—all of which incur costs. Moreover, depth cameras generate large amounts of data, requiring high-performance processing units, computational chips, data transmission, and redundancy designs. ToF and structured light cameras are even more expensive and involve issues like active light sources and safety certifications. Integrating them into a vehicle is not only costly but also requires careful engineering.

Thus, while depth cameras have their strengths, they are not 'perfect.' They provide intuitive spatial information and are an important supplement to visual systems, but they are far from sufficient for handling autonomous driving perception tasks alone. Mature solutions rely on multi-sensor fusion, allowing depth cameras, radar, LiDAR, and ordinary cameras to each play their role and compensate for one another's weaknesses. Only in this way can vehicles 'see clearly' and 'see steadily' in complex environments.

When to Utilize Depth Cameras and How to Integrate Them with Other Sensors

In autonomous driving system design, the choice between depth cameras and other sensors depends on the task, scenario, and cost. Close-range, low-speed scenarios (such as automatic parking, driver monitoring, and in-cabin interaction) are well-suited for ToF or structured light cameras, as these scenarios demand high short-range accuracy and operate in relatively controlled environments. When high-resolution geometric information is required for fine positioning or obstacle boundary judgment, stereo vision paired with high-resolution cameras is a cost-effective choice, but it must be accompanied by powerful disparity calculation and reliable online calibration.

When it comes to highway or long-distance perception scenarios, LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) and millimeter-wave radar still stand out as the predominant options. The long-range resolution and precision offered by LiDAR, coupled with the ability of millimeter-wave radar to perform reliably in inclement weather conditions, make it challenging for optical depth cameras to entirely take their place. In these contexts, depth cameras act as a complementary tool for geometric perception. They integrate data from RGB cameras, depth cameras, radar, and LiDAR, capitalizing on the unique strengths of each sensor while compensating for their respective limitations. For instance, depth maps can swiftly filter out nearby obstacles; RGB cameras are adept at semantic recognition; radar is capable of estimating speed and providing consistent detection in unfavorable weather; and LiDAR excels at achieving precise long-distance positioning. Furthermore, depth cameras can alleviate certain computational loads: in areas where depth is already known, numerous visual algorithms can bypass costly three-dimensional reconstruction processes and make decisions directly within the depth space.

Certainly, numerous practical considerations must be taken into account. These encompass sensor placement and field-of-view coverage, ensuring sensor synchronization and timestamp precision, devising data bandwidth and compression strategies, implementing online denoising and anomaly detection, formulating degradation detection and fallback strategies for varying lighting and weather conditions, as well as establishing redundancy and fault-switching mechanisms. All these aspects are crucial when transitioning depth cameras from the laboratory setting to automotive-grade product development.

-- END --