Relaxing the 'Internal Combustion Engine Ban': European Automakers Enter a 'Reprieve Period'

![]() 12/22 2025

12/22 2025

![]() 532

532

Amidst enthusiastic responses from European automakers, the industry crisis persists.

On December 16, the European Commission unveiled a highly anticipated proposal, substantially revising the 'internal combustion engine ban' originally set to take effect in 2035. The new proposal adjusts the CO2 reduction target for new vehicles in 2035 from '100% reduction compared to 2021 levels' to a 90% reduction.

While the proposal has been met with enthusiasm from European automakers, it also reflects the European Commission's compromise with reality. The European automotive market has not achieved widespread electrification as envisioned, lagging behind average levels instead.

According to the latest data from the European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA), as of October 2025, the market share of new battery electric vehicles (BEVs) in the EU has reached 16.4%, a significant increase from 13.2% in the same period in 2024.

However, this growth rate remains slow compared to the explosive growth required to achieve the 55% reduction target by 2030 and the original zero-emission goal by 2035. The ACEA explicitly stated in its October data release: 'At the current stage of transition, this growth rate still falls short of expectations.'

On the other hand, the automotive industry is be caught in ['trapped in'] a dilemma of 'increased production but declining revenue,' even facing losses. As transition pressures intensify, the German automotive sector experienced a severe 'wave of layoffs' in 2025, while more severe profitability issues continue to exacerbate industry conflicts.

Faced with this crisis, the European Commission has been forced to compromise with automakers. Compared to carbon emissions, the employment of 13.6 million people demands greater attention.

However, in the new proposal, the Commission still seeks to maintain face by setting goals that are not easily achievable.

Reprieve Does Not Equate to Relaxation

A closer look at the new proposal reveals that the so-called 'relaxation' does not mean the European Commission has abandoned its zero-emission goal. The new regulations set complex conditions, essentially serving as a transitional plan reached through multi-party compromises.

First, the most controversial change is the reversal from a 100% reduction to a 90% reduction. While this may seem like a step backward, a closer comparison reveals that the remaining 10% holds little significance for internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs).

This 10% corresponds to an average carbon emission target of 12g/km for automakers in the EU by 2035. For context, the 2025 carbon emission standard in Europe is 93.6g/km, while China's 2024 standard for domestic automakers is 76g/km.

Notably, China's new energy vehicle penetration rate reached 47.6% in 2024, nearing 50%. Although Europe's penetration rate is lower, it still stands at 20%.

Achieving 12g/km in carbon emissions is nearly impossible with current internal combustion engine technology, whether extended-range or hybrid. After over a century of internal combustion engine development, European automakers have exhausted their research capabilities without resolving this issue. Developing a compliant internal combustion engine within the next decade seems like a pipe dream.

More importantly, the European Commission has blocked another 'effective' short-term emission reduction method: plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), which have seen rapid sales growth in Europe in 2025. According to reports, the EU plans to adjust the Utility Factor for PHEVs in 2027, reducing their weight in emission reduction calculations, effectively closing this avenue.

Additionally, the remaining 10% allowance for internal combustion engines is not freely available. The EU has set strict conditions: vehicles must be produced using low-carbon steel manufactured in the EU or use synthetic and biofuels, which can only offset up to 3% of emissions.

Of course, this 10% concession is not unconditional. The carbon emission pressure for passenger vehicles has been shifted to commercial and official sectors. While the proposal 'relaxes' requirements for passenger vehicles, it significantly tightens constraints on corporate fleets and commercial vehicles. The new regulations plan to set binding minimum quotas for low-emission and zero-emission vehicles in corporate fleets across member states.

For example, in Germany, by 2030, 77% of vehicles in large corporate fleets must be low-emission or zero-emission, with zero-emission vehicles accounting for no less than 54%. Meanwhile, the 2030 emission reduction target for light commercial vehicles has been lowered from the original 50% to 40%.

This shift transfers the rigid emission reduction responsibilities from private consumption to organizational and commercial operations.

Achieving emission reduction standards in the commercial vehicle sector requires meeting targets earlier, by 2030, intensifying the pressure. This explains why, after the proposal's release, Volvo was the only European automaker with executives criticizing the move as a 'terrible idea.'

Electrification Cannot Bypass China

Of course, European automakers' efforts have yielded some results. Beyond the 10% carbon emission allowance, the relaxation of annual targets before 2035 provides much-needed breathing room for European automakers.

First, the introduction of a 'carbon credit banking' system has become a lifeline for automakers.

Faced with transition pressures, the EU has repeatedly flexibilized emission reduction assessment rules in 2025. The key revision this time is changing the carbon emission assessment from a single-year target in 2025 to an average over three years (2025-2027).

This means automakers can offset excess emissions in one year with reductions in other years. The European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA) explicitly stated that this provides the industry with 'much-needed breathing space.'

Similarly, this policy will apply from 2030 to 2032, easing annual targets for automakers.

The biggest beneficiary of this policy is the Volkswagen Group. Based on data from the first 11 months of this year, under the old rules, Volkswagen faced emission fines of up to €4 billion. This proposal's clause has essentially rescued Volkswagen's struggling profitability.

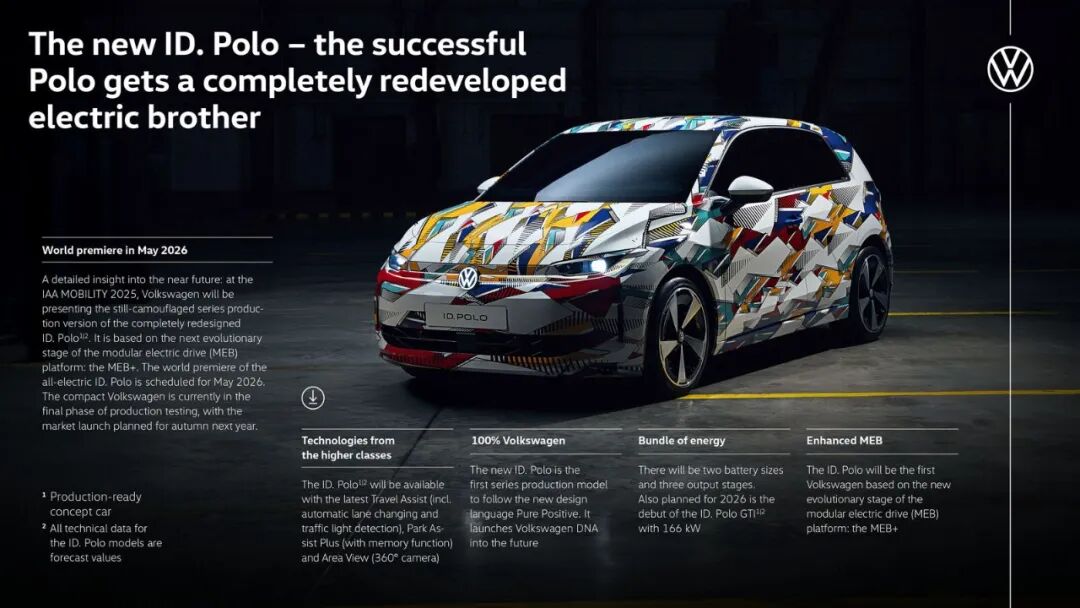

Additionally, the proposal introduces a 'super-credit' mechanism specifically to encourage small electric vehicles. Before 2034, each small battery electric vehicle (BEV) with a length under 4.2 meters sold will count as 1.3 vehicles in emission calculations for automakers, providing a green channel for European automakers.

Since this super-credit applies only to vehicles produced in the EU, Chinese products, which currently enjoy strong sales in Europe, will not receive additional credits.

Shortly after these proposals were announced, Volkswagen released more information about the ID.Polo, confirming its European launch in spring 2026 at a price of around €25,000 (approximately ¥200,000).

Multiple sources confirm that the ID.Polo will not be a global model, especially not available in the Chinese market. The reason is straightforward: the current domestic price of the Volkswagen ID.3 has already dropped to ¥119,900, sparking outrage among European consumers. If the ID.Polo were sold in China, its price would likely be even lower.

Beyond incentive policies, the proposal explicitly supports electrification by providing €1.8 billion in funding for local battery manufacturers to secure supply chains.

While these aspirations are commendable, members of the European Commission's proposal team may not have considered that the new proposal's content will not accelerate Europe's automotive electrification.

A typical case is Renault's launch of the electrified version of its classic model, the Twingo, in Europe this year, set to officially hit the market in early 2026.

However, Europeans may not expect that this classic European model, aside from being manufactured in Europe, has little else to do with Europe.

This model represents Renault's new development approach, summarized as 'the Chinese handle the technology, while the French handle the carpets.'

Although Renault has largely exited the Chinese automotive market, it established the ACDC development center in Shanghai, fully leveraging domestic new energy technologies to achieve a low-investment, high-efficiency development rhythm.

Reportedly, the research and development cost of the electric Twingo is only half of previous European models, while the development cycle has been shortened by 40%. This explains how Renault can produce a small car priced under €20,000 in a short time.

Beyond development, the production of this model relies heavily on 'Chinese hearts.' It has been confirmed that the electric drive is supplied by SAIC Motor, while the battery is a lithium iron phosphate battery provided by CATL.

Perhaps Europeans did not anticipate that in just a few years, their proud automotive manufacturing would undergo such a transformation. More surprisingly, the electric Twingo is eligible for government subsidies of €5,000 in several European countries.

Even under the framework of a 'European-made model,' the EU cannot bypass China's leading advantages in core electric vehicle components and large-scale manufacturing.

The EU's relaxation of the 2035 'internal combustion engine ban' is primarily a political and economic balancing act based on current challenges. It reflects Europe's difficult equilibrium between environmental ambitions, industrial competitiveness, energy security, and consumer acceptance.

However, this policy adjustment does not address the fundamental decline of Europe's automotive industry. It fails to automatically resolve issues such as high manufacturing costs, insufficient competitiveness of electrified products, and supply chain weaknesses.

Many provisions in the new regulations aimed at protecting local industries represent defensive 'economic nationalism' measures, whose long-term effectiveness remains uncertain.

True revival does not lie in how much longer policies can extend the lifespan of internal combustion engines but in whether Europe can rebuild its core technological competitiveness, cost control capabilities, and brand appeal in the new arena of electrification and intelligence.

Relaxing the ban is merely a disguised reprieve. For Europe's automotive industry, while it has gained breathing room, the ultimate outcome will still be determined by competitive strength on the field.

The answer to whether it can achieve revival will never be found in Brussels' regulatory texts but in the laboratories, factories, and decision-makers' hands in Stuttgart, Wolfsburg, Munich, and beyond.

Note: Image sources are from the internet. If there is any infringement, please contact us for removal.

-END-