Betrayed by Tesla, Japan’s Once-Dominant Power Battery Giant Fades from Global Prominence

![]() 01/04 2026

01/04 2026

![]() 515

515

The trajectory of Panasonic’s rise and fall is not overly complex. Its pursuit of immediate profits clashed with Musk’s long-term vision, leaving both sides dissatisfied. To retain Tesla as a major client, Panasonic made excessive concessions, leading to resource depletion. Coupled with Japan’s misguided bet on hydrogen energy and limited support from its domestic industrial ecosystem, Panasonic now faces fierce competition from Chinese rivals, sliding toward irrelevance.

In 2015, teenage prodigy Li Yinan unveiled his first electric vehicle, the Niu N1, with Panasonic’s 18650 lithium-ion batteries as a key selling point. At the time, Panasonic symbolized cutting-edge battery technology—a coveted leader in the field.

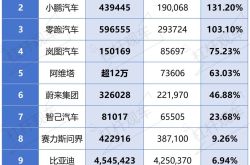

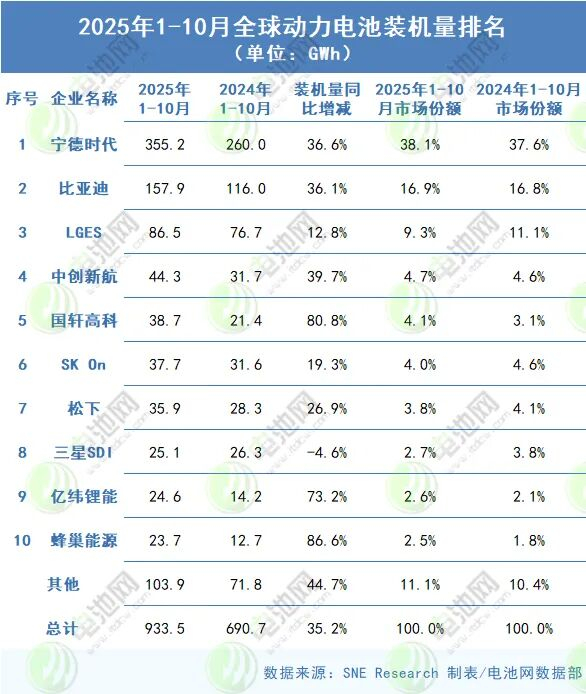

However, a decade later, from January to October this year, Panasonic has tumbled to seventh place in global power battery installations, with 35.9 GWh—a mere fraction of CATL’s output.

From invincibility to obscurity, Panasonic’s decline has been swift.

#1

Invincibility

Panasonic’s dominance coincided with Japan’s early leadership in rechargeable batteries. Founded in 1918, the company began producing batteries in 1931 for home appliances like refrigerators, shavers, and rice cookers, as well as consumer electronics.

In 1983, Dr. Akira Yoshino developed a groundbreaking rechargeable battery using polyacetylene for the anode and lithium cobalt oxide for the cathode, marking the dawn of the modern lithium-ion era.

Eight years later, Sony commercialized the world’s first lithium-ion battery. Panasonic followed suit, successfully developing rechargeable lithium-ion batteries in 1994 and venturing into automotive power batteries.

By 2000, Japanese firms controlled approximately 93% of the global lithium-ion battery market. Panasonic entered the automotive sector in 1997, forming a joint venture with Toyota to develop nickel-metal hydride batteries for the Prius, Toyota’s first hybrid model.

Panasonic not only entered the automotive battery market early but also established a near-monopoly. Its supply chain dominance was so strong that even global sales leader Toyota relied heavily on its technology. In 2006, Toyota began developing plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) with lithium-ion batteries, sourcing primarily from Panasonic and Sanyo (later acquired by Panasonic).

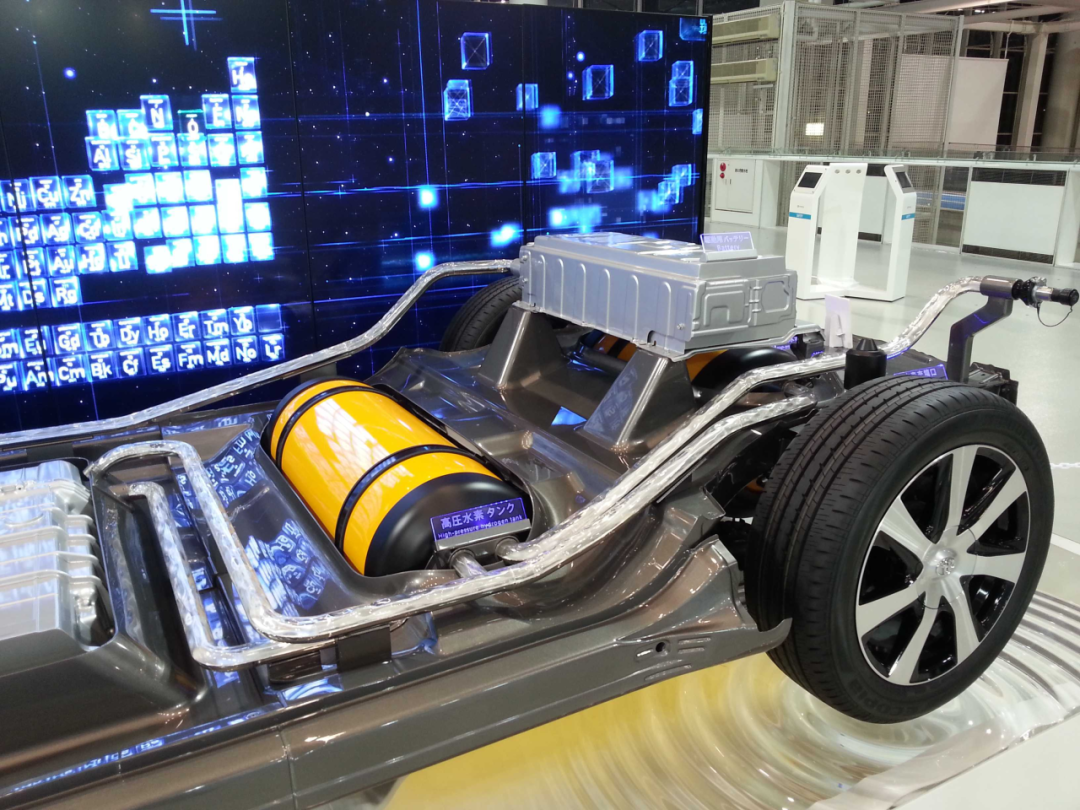

Japanese dominance persisted until around 2008, when a pivotal shift occurred—the national bet on hydrogen fuel cells.

Despite breakthroughs in lithium-ion technology, Japanese firms abandoned patent consolidation and instead gambled on hydrogen. They argued that lithium-ion batteries had limited energy density, making hydrogen fuel cells a cleaner, more efficient alternative. Hybrid technology was seen as transitional, with hydrogen energy expected to replace it upon maturity.

This national strategy left Japanese firms monopolizing hydrogen patents but neglecting lithium-ion advancements.

Tesla’s emergence, bypassing hydrogen for lithium-ion batteries, disrupted Japanese calculations. Meanwhile, South Korean conglomerates rapidly acquired lithium-ion patents, with LG Energy Solution and Samsung SDI becoming industry giants.

Japan’s misjudgment eroded its technological edge. As the lithium-ion market soared, Panasonic became Japan’s sole remaining player, barely keeping the country competitive.

Panasonic’s survival depended on one client—Tesla. In 2008, it acquired Sanyo Electric, Tesla’s chosen supplier, and naturally became Tesla’s exclusive battery provider. Its 18650 cylindrical batteries set a benchmark for quality in the Chinese market.

#2

Love-Hate Relationship

In 2008, Tesla launched its first sports car, the Roadster, priced at $110,000—$10,000 above Musk’s initial estimate. High battery costs were a key factor, with rumors suggesting the battery management system alone cost $20,000.

Musk, a proponent of extreme cost control, needed a capable supplier. Panasonic, reeling from losses in plasma TVs and smartphones, sought new growth avenues. The two sides found common ground.

At the time, Tesla was plagued by production delays and bankruptcy rumors. In 2009, Panasonic supplied Tesla with 18650 batteries. A year later, it invested $30 million in Tesla’s IPO, providing capital and industrial chain support.

In 2011, to secure Model S production, Tesla and Panasonic signed a supply agreement for 640 million 18650 cells. By 2013, the deal expanded to 1.8 billion cells, making Panasonic Tesla’s exclusive strategic supplier.

Tesla elevated Panasonic’s profile, with its market share once reaching 40%. The honeymoon peaked with their joint investment in the Gigafactory.

In March 2014, Tesla planned a $5 billion factory in Nevada to reduce battery costs. By then, the Model S had turned profitable, giving Tesla the upper hand. Musk urged Panasonic to invest in the factory.

Panasonic faced internal resistance but, unwilling to lose Tesla, newly appointed President Kazuhiro Tsuga firmly backed the partnership. “Investing in the Gigafactory is our only wise choice,” he stated. Panasonic ultimately invested $1.6 billion.

For Tesla’s second battery factory in New York, Panasonic supplied solar roof batteries. Yet, these efforts exhausted Panasonic financially. The Gigafactory drained its resources, leaving no room for capacity expansion.

In 2017, the Model 3 debuted to acclaim but faced production delays. Tesla plunged into “production hell,” suffering its largest quarterly loss. Short sellers circled, executives resigned, and pre-order customers demanded refunds.

Panasonic took the blame, citing insufficient battery capacity. Tsuga visited Nevada nearly every quarter to inspect progress.

Musk, however, sought more reliable solutions. In 2018, Tesla began constructing its Shanghai Gigafactory to alleviate production crises and invited Panasonic to invest.

By then, Panasonic was exhausted. Musk had consistently demanded price cuts, pushing battery costs per unit energy below those of Chinese firms. As Tesla’s factory progressed, Panasonic’s investments spiraled beyond the initial $1.6 billion. Meanwhile, Tesla delayed battery payments, straining Panasonic’s finances.

Having accompanied Tesla through years of turmoil, Panasonic remained unprofitable, forced to cut costs and increase investments. The Shanghai factory became the flashpoint for their conflict.

Musk swiftly demonstrated capital’s ruthlessness. The Shanghai factory marked the beginning of their rift.

#3

Ultimate Rival

When asked in 2019 if he regretted investing in Tesla’s battery factory, Tsuga replied, “Yes, absolutely”—a stark reversal from his earlier determined stance.

After the Shanghai factory’s establishment, Tesla adopted a diversified battery supply strategy. Musk spared no sentiment for Panasonic: “Tesla will manufacture all battery packs and modules at its China Gigafactory… Suppliers will likely come from multiple companies… Our long-term goal is local production for local markets, with price being crucial.”

Implicitly, Panasonic’s prices were too high. Diversification was vital to securing Tesla’s production.

In April 2019, Musk publicly accused Panasonic’s battery production line of insufficient capacity, limiting Model 3 output. Tsuga retorted that Tesla’s production issues stemmed from itself, accusing Musk of shifting blame. Surface harmony vanished.

Betrayed by Tesla, Panasonic had to diversify its client base, establishing the TTP system—Tesla, Toyota, Panasonic. Yet, without exclusive Tesla cooperation, Panasonic’s core clients dwindled.

Meanwhile, new rivals emerged—Chinese battery manufacturers.

In 2007, Wang Chuanfu registered a battery company in Huizhou, establishing a lithium iron phosphate power battery production base, marking China’s entry into the sector. Around the same time, Zeng Yuqun at ATL foresaw the future of new energy vehicles.

These companies eventually became known as “Ningwang” (CATL) and “Diwang” (BYD).

Japanese and Korean firms did not remain idle. Around 2015, during China’s nascent new energy vehicle era, they entered the Chinese market.

Today, many discuss Chinese firms’ price wars, unaware that Japanese and Korean firms initially employed the same tactic. When domestic ternary lithium battery prices averaged 2.5–3 yuan/Wh, Japanese and Korean firms offered 1 yuan/Wh, rapidly seizing market share.

The following year, Chinese industrial policies supported domestic firms. The “Automotive Power Battery Industry Norms” enterprise directory excluded foreign battery manufacturers. Domestic lithium batteries surged alongside China’s new energy vehicle industry.

By 2017, CATL’s shipments surpassed Panasonic’s, claiming the global top spot for the first time.

This was an asymmetric competition. Chinese automakers seized the new energy trend, supported by China’s robust supply chain ensuring production capacity, and backed by full industrial policy support—advantages Panasonic and LG could not match.

Japan and South Korea have limited markets, with automakers providing only modest support to domestic power battery firms. Panasonic and LG had to seek overseas markets, a complex landscape requiring adaptation to diverse policies, environmental groups, LGBT communities, unions, and other stakeholders—conditions CATL and BYD did not face.

Chinese firms, driven by a large market and fierce competition, remained pragmatic and customer-focused, unlike Panasonic’s misplaced priorities.

After Panasonic’s conflict with Tesla, Musk approached Zeng Yuqun, seeking lower-cost batteries. Zeng’s response was definitive: “I will have a solution.”

This direct and assured style resonated with Tesla. In 2020, CATL officially became Tesla’s power battery supplier, reportedly saving Tesla $6,000–$12,000 per vehicle.

In 2022, China’s new energy vehicle market exploded, coinciding with raw material price hikes. CATL became virtually the only option and the largest cost source. At the World Power Battery Conference that year, GAC Group publicly lamented: “Power batteries account for 40%–60% of vehicle costs and keep rising. Are we working for CATL?”

Frustrated by CATL’s market dominance, manufacturers sought alternatives. While this seemed like an opportunity for Panasonic, it instead dealt a further blow to its decline.

SVOLT, Guoxuan High-Tech, EVE Energy, and SVOLT Energy seized the chance, rapidly rising.

In 2021, Panasonic was still third globally; just four years later, it had fallen to seventh. But the decline continues.

#4

Sunset

According to the latest report, from January to October this year, six of the top ten global power battery installers are Chinese companies.

All four foreign companies have experienced a year-on-year decline in market share without exception. Meanwhile, Chinese companies, except for CATL, are all experiencing growth. This implies that the market shares of companies like Panasonic are being comprehensively seized by domestic companies.

It’s not that Panasonic is underperforming. Due to the beta growth of new energy vehicles, the installed capacity of most battery manufacturers is increasing. Panasonic’s real dilemma is that the growth rate of Chinese midstream battery manufacturers is faster. Sailing against the current, if Panasonic slows down, it effectively means moving backward.

Currently, the competition in power batteries has been elevated to a new dimension by Chinese manufacturers.

BYD has introduced the Blade Battery. After enhancing the energy density of lithium iron phosphate batteries, they have made a comeback, offering not only lower costs than ternary lithium batteries but also significant improvements in range.

SVOLT Energy Technology has adopted a stacking technology to replace the common winding technology and launched its self-developed short blade battery series.

Four years ago, Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Limited (CATL) unveiled its sodium - ion battery. Under normal temperature conditions, this battery can reach an 80% charge in a mere 15 minutes. Even when operating in a frigid environment of minus 20°C, it still retains over 90% of its discharge capacity. Moreover, its system integration efficiency can surpass 80%.

Solid - state batteries are steadily making their way into the commercialization stage.

On October 18th of this year, Chery Automobile, in collaboration with Gotion High - Tech, showcased the Rhino S all - solid - state battery module. This is a battery module featuring a cell energy density of up to 600Wh/kg, getting close to the theoretical limit of lithium batteries and extending the driving range to 1,200 - 1,300 kilometers.

Sunwoda has launched the 'Xin·Bixiao,' a brand - new polymer solid - state battery. This battery can attain an energy density of up to 400Wh/kg.

Weilai New Energy is currently undergoing listing counseling and has plans to go public on the Growth Enterprise Market, with the ambition of becoming the 'first solid - state battery stock.'

All - solid - state batteries, characterized by high safety, high energy density, and long cycle life, have emerged as the pivotal technology for reshaping the energy landscape. In this context, Chinese companies are stepping up their efforts and are making a comprehensive push to seize the market. Panasonic, once the kingpin of the power battery industry, is now destined to face a formidable challenge that could significantly diminish its standing.

Now, it appears that the reasons behind Panasonic's decline from its heyday are not overly complex. When faced with Musk, its pursuit of immediate profitability simply does not follow the same rationale. The initial exclusive cooperation did indeed provide Panasonic with an entry pass. However, limitations within the Japanese industrial chain, insufficient corporate support, and misguided technological routes have gradually eroded its initial advantages. In an attempt to retain its major client, Panasonic made excessive concessions and overlooked the fundamental conditions for establishing strategic cooperation. As a result, it ultimately lost its exclusive cooperation with Tesla and has been comprehensively outpaced by Chinese companies.

Chinese companies are already reaping the benefits of the Davis Double Play effect, with a continuously expanding market size and widening leading advantages. Panasonic is struggling to avoid falling into a downward spiral.