Is It Truly Due to the Inability to Repatriate Profits That No One Dares to Establish Car Factories in India?

![]() 01/23 2026

01/23 2026

![]() 362

362

Lead

Introduction

It is reported that India feels at a loss regarding the absence of automakers in its electric vehicle manufacturing initiative.

When the application window set by India's Ministry of Heavy Industries for the Scheme for Promotion of Manufacturing of Electric Passenger Cars in India (SPMEPCI) closed on October 21, 2025, the outcome was nothing short of embarrassing: not a single global automaker submitted an application.

This plan, seen as India's bid to become a global hub for electric passenger vehicles, was bluntly described by senior internal officials as “a mere formality,” reduced to a dead letter. Amid the global electric vehicle industry's accelerated expansion, India had intended to leverage its vast market potential to attract global capital but instead faced a collective rebuff.

Many attribute this to the notion of “make in India, spend in India, and forget about taking profits home,” but a deeper analysis reveals that concerns over profit repatriation are merely superficial. Beneath the surface lies a complex interplay of factors: inherent flaws in policy design, uncertainties in trade negotiations, critical supply chain shortcomings, and a fragile market foundation.

The collective hesitation of global automakers essentially represents a rational avoidance choice after a comprehensive weighing of risks and opportunities in the Indian market. This outcome has ultimately dealt a severe blow to India's vision of becoming a manufacturing powerhouse.

01 Major Issues in Policy Formulation

Indian insiders admit that the impracticality of policy design and uncertainties in the trade environment constitute the first major barrier for global automakers entering the Indian market, with their deterrent effect far outweighing mere profit considerations.

The Indian government's original intention in launching the SPMEPCI plan was to exchange tariff incentives for substantial investments and localized production from global automakers, thereby driving the rise of the domestic electric vehicle industry. This approach is not unreasonable in itself, but the harshness and ambiguity of the policy terms have deterred automakers.

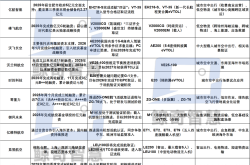

According to the plan's requirements, participating OEMs must commit to investing at least ₹415 billion (US$500 million) to establish manufacturing facilities and achieve a domestic value addition (DVA) rate of 25% within three years, increasing to 50% within five years, with penalties for non-compliance.

Such high investment thresholds and stringent localization requirements impose extremely high demands on automakers' financial strength and supply chain integration capabilities. Even more unreasonably, the policy excludes significant land investments from the total investment calculation, further increasing the financial burden on companies.

Meanwhile, the requirements of ₹100 billion in global revenue and ₹30 billion in global fixed assets directly exclude smaller electric vehicle manufacturers. Even large automakers must carefully evaluate the balance between inputs and returns.

If stringent policy terms represent overt obstacles, then the unresolved India-EU Free Trade Agreement (FTA) negotiations serve as a hidden factor deterring automakers from taking the plunge.

Multiple original equipment manufacturers have explicitly stated that their participation in the SPMEPCI plan depends on the final outcome of the India-EU FTA negotiations. Currently, India imposes over 100% tariffs on imported vehicles, and the 15% preferential tariff rate offered under the SPMEPCI plan is meant to be a core incentive for automakers.

However, the EU has explicitly demanded that India significantly reduce or even eliminate automotive import tariffs during trade negotiations, and the Indian government has shown signs of concession, considering a phased reduction of import vehicle tariffs to 10%. Once this negotiation result materializes, the tariff advantage of the SPMEPCI plan will vanish, leaving automakers facing the risk of unrecoverable substantial investments.

This uncertainty over policy incentives places automakers in a dilemma of whether to invest or not. After all, for the capital-intensive automotive industry, any large investment requires a stable policy environment as a guarantee. No one is willing to bet billions of dollars when the policy outlook remains unclear.

More notably, when automakers proposed policy revisions, the Indian government not only failed to respond positively but explicitly stated that “no proposals for revision or extension of the deadline are currently under consideration.” This rigid attitude further exacerbated automakers' concerns, making them more inclined to wait and see rather than take risks.

Additionally, misaligned policy incentives have significantly reduced the plan's appeal. The SPMEPCI plan limits import tariff reductions to high-value complete vehicles priced at US$35,000 and above, a design intended to incentivize automakers to produce mid- to high-end models in India but one that is severely out of touch with actual market demand.

Currently, the penetration rate of electric vehicles in the Indian market is less than 4%, expected to reach only 6% by 2025, and the price of mainstream domestic models is half that of Tesla's cheapest model. Demand for high-end models is extremely limited, making it difficult for automakers to achieve large-scale sales even if they import high-end models under preferential tariffs, let alone support the cost-sharing of localized production.

This disconnect between policy design and market demand significantly diminishes the practical value of tariff incentives, failing to effectively stimulate automakers' investment enthusiasm. Meanwhile, the Indian government's refusal to offer tariff incentives for internal combustion engine vehicle production has disappointed some automakers still balancing the transition between fuel-powered and electric vehicles, further reducing their willingness to participate in the plan.

02 Lack of a Favorable Development Environment

In reality, critical supply chain shortcomings and a weak market foundation constitute the second major barrier for global automakers building factories in India, with their constraints on industrial localization no less significant than policy and trade factors.

The development of the electric vehicle industry is highly dependent on the support of core raw materials and infrastructure, areas where India suffers from fatal flaws. Rare earth magnets, essential raw materials for electric vehicle motors, directly determine automakers' production security.

Although India ranks third globally in rare earth reserves with 6.9 million proven tons, its mining and processing capabilities are extremely underdeveloped, contributing less than 1% to global rare earth production. Rare earth permanent magnets required for electric vehicle production rely heavily on imports from China.

After China tightened rare earth export controls, India's supply of rare earth permanent magnets plunged into crisis, with production at multiple automotive component manufacturers continuously declining and even facing the risk of production halts. For global automakers, this high degree of uncertainty in the supply of core raw materials represents an unacceptable production risk.

Although the Indian government plans to invest ₹25 billion to support the development of the rare earth permanent magnet industry, and some companies are attempting to develop rare earth-free alternatives, the former requires long-term policy support and technological accumulation, while the latter needs at least 6-9 months of research and development and faces multiple unknown challenges in efficiency and cost, offering no short-term solution to supply chain shortages.

Under such circumstances, if automakers rashly build factories in India, they will face the dilemma of having no raw materials to work with. Even if localized production is achieved, production may still be forced to halt due to raw material shortages.

The severe lag in charging infrastructure further undermines automakers' investment confidence from the market consumption side. Currently, Indian consumers' biggest concern about electric vehicles is range anxiety caused by inadequate charging facilities.

Although the Indian government has been promoting charging infrastructure development, progress has been slow, with charging stations concentrated mainly in a few major cities while vast rural and underdeveloped areas remain nearly blank. More critically, India's charging infrastructure relies heavily on imported electronic components and semiconductors, with cumbersome approval processes, compounded by frequent power outages in some regions, further reducing the reliability of charging services.

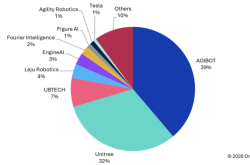

Additionally, the competitive landscape and road conditions in India's domestic automotive market have become hidden barriers for global automakers entering the market. Currently, Tata Motors dominates the Indian electric vehicle market with over 60% share, followed by MG Motor with 22%, giving domestic brands a strong first-mover advantage.

Global automakers entering the Indian market must not only face multiple challenges from policies and supply chains but also engage in fierce competition with domestic brands, undoubtedly raising the difficulty of market entry. Meanwhile, poor road conditions in some Indian regions impose higher reliability requirements on electric vehicles' chassis, batteries, and other components, requiring automakers to invest additional R&D costs for model adaptation, further reducing the attractiveness of the Indian market.

Notably, global automakers' concerns about Chinese automakers leveraging India's free trade agreements to enter the local market have also intensified their wait-and-see attitude. Under the superimposed risks, global automakers' decision to temporarily shelve plans for building factories in India is undoubtedly the most rational business choice.

It can be said that these factors, intertwined, collectively form a high-risk barrier for global automakers entering the Indian market. For the Indian government, realizing its vision of becoming a global electric vehicle hub requires far more than just introducing preferential policies. Otherwise, the “Made in India” electric vehicle dream will likely continue to stall amid the collective hesitation of global automakers.

Editor-in-Chief: Du Yuxin Editor: He Zengrong

THE END