MiniMax and Zhipu Going Public: The Ripple Effect of China's AI Industry Chain is Coming

![]() 01/18 2026

01/18 2026

![]() 495

495

The listings in early 2026 did not simply open a financing window but introduced a new industrial operating model. Model companies gain sustained investment capabilities, upstream suppliers secure long-term order expectations, and downstream partners acquire more controllable technical collaborators. The industry chain is transitioning from a trial phase to a collaborative stage centered around long-term capacity building.

China's large model competition has entered a phase defined by patience, capital, and engineering prowess.

Author | Doudou

Editor | Piye

Produced by | Industrial Insights

In early 2026, Zhipu and MiniMax successively went public on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, with less than 48 hours between their debuts.

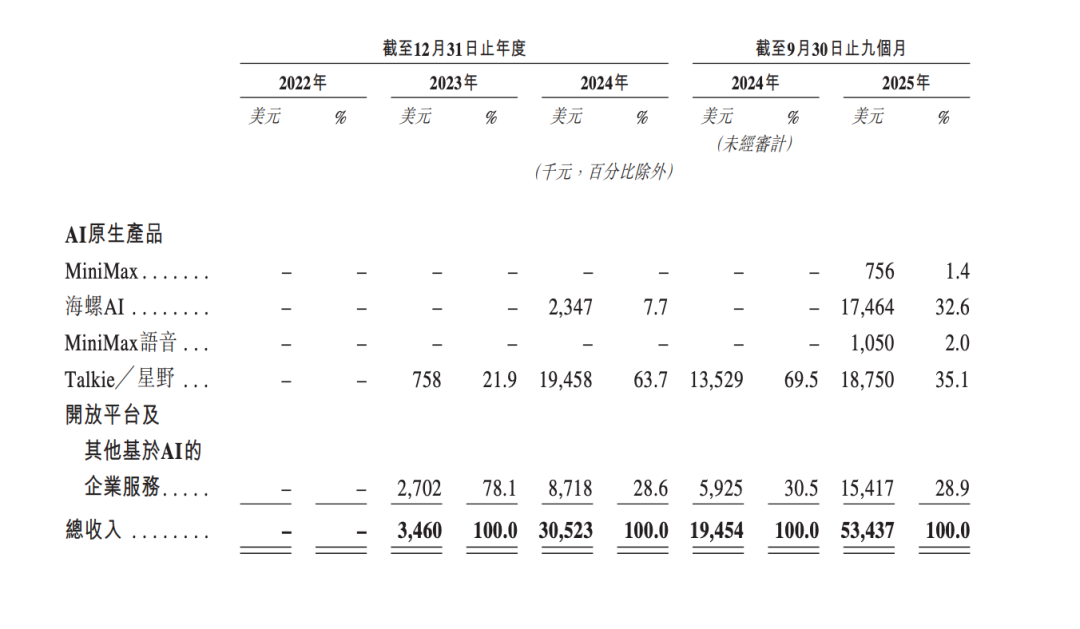

While their business models differ—Zhipu focuses on foundational models and government-enterprise projects, whereas MiniMax leans toward multimodal and consumer applications—both were placed on the same coordinate system at the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, becoming two typical samples for the capital market to understand China's large models.

Market feedback directly reflected the value of these two companies. Data shows that MiniMax priced its shares at HK$165, with its stock price more than doubling on the first day of trading, becoming one of the strongest-performing new listings on the Hong Kong stock market since the beginning of the year. Zhipu's public subscription multiple exceeded 1,000 times, with its stock price once surpassing HK$130 during trading.

If we view this wave of AI technological advancement as a new industrial narrative, then the listings of MiniMax and Zhipu have clearly become a significant milestone where public markets take over from venture capital (VC).

Against this backdrop, some questions have become clear and urgent: Why now? Why the same listing path? What changes will occur in the future AI industry chain?

I. Large Model Companies Need a New Approach

Looking back at the past two years, China's large model industry has undergone several notable shifts.

From the initial validation phase of whether large models could be built, to the subsequent ability differentiation phase of who could survive, the focus has now shifted to the scaling exploration phase—that is, who can achieve true business scalability under high-investment conditions.

This change is first reflected on the user side. According to the CNNIC's "Generative AI Application Development Report (2025)," as of June 2025, China's generative AI user base reached 515 million, with a penetration rate of 36.5%, and over 260 million new users added within six months. During the same period, the Cyberspace Administration of China disclosed that 346 generative AI services had completed registration.

The expansion of the user base and the gradual formation of a regulatory framework indicate that large models have moved beyond the conceptual validation stage. Enterprise clients are starting to place orders, industry pilots are being replicated, and the core challenges for model companies have shifted from what they can do to how long they can sustain and how far they can scale.

In the entire foundational model sector, from a business model perspective, B2B resembles a productivity competition where enterprises are only willing to pay a premium for the strongest models. The B2C moat increasingly relies on contextual experience value rather than mere parameter scale. However, regardless of whether they focus on B2B or B2C, the underlying requirements cannot avoid compute power, training, talent, and engineering systems—all of which entail heavy investment.

It is evident that some cloud providers have begun investing resources far exceeding early expectations. For example, in 2025, Alibaba announced a three-year investment of RMB 380 billion in cloud and AI infrastructure. Alibaba Cloud's latest financial report also revealed that its capital expenditures over the past four quarters reached US$12 billion, a typical example of "big player" investment. On the other hand, ByteDance has frequently been mentioned in the context of large-scale procurements of compute power and GPUs.

These actions indicate that leading players are raising the competitive threshold to high capital investment. The competition is not just about model capabilities but also about who can sustain high-intensity investment for longer periods.

However, even if model companies maintain high investment levels, it is difficult to achieve sufficiently rapid returns in the short term, and the pressure from financing and cash flow will be prolonged.

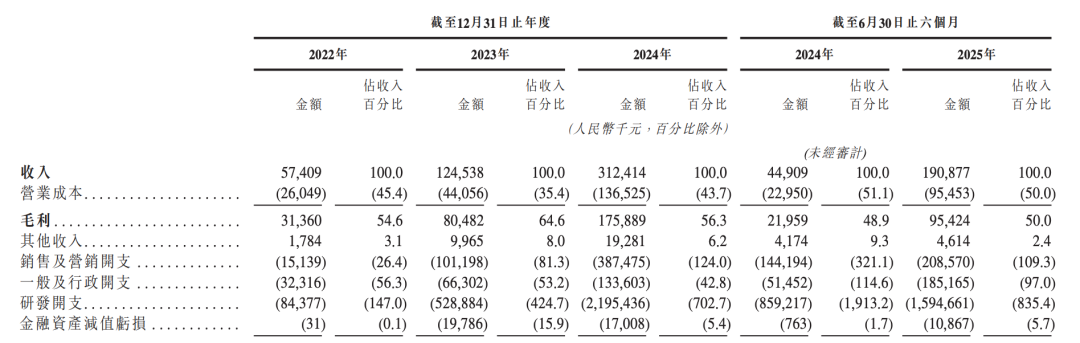

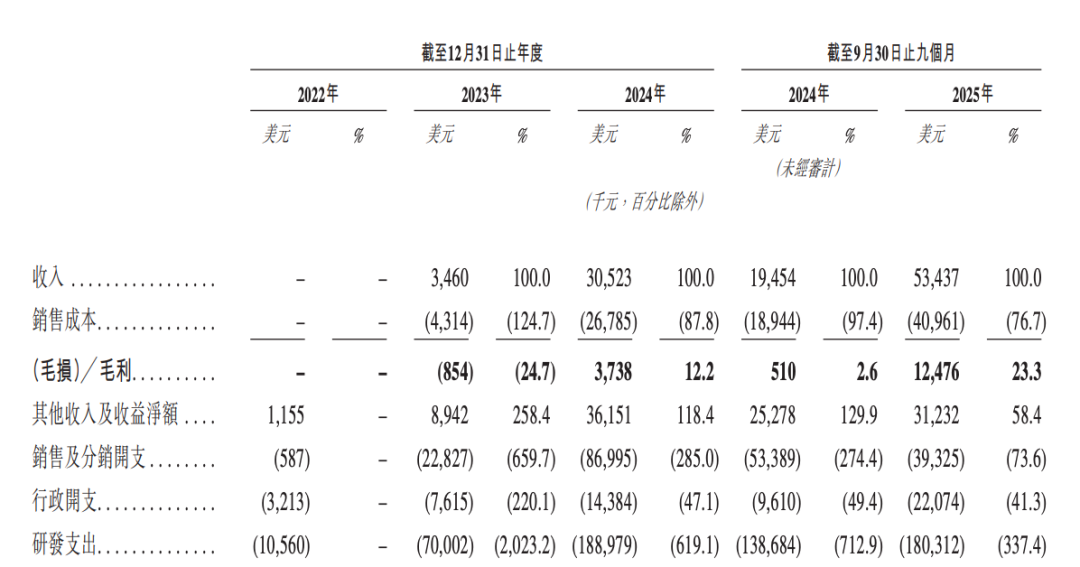

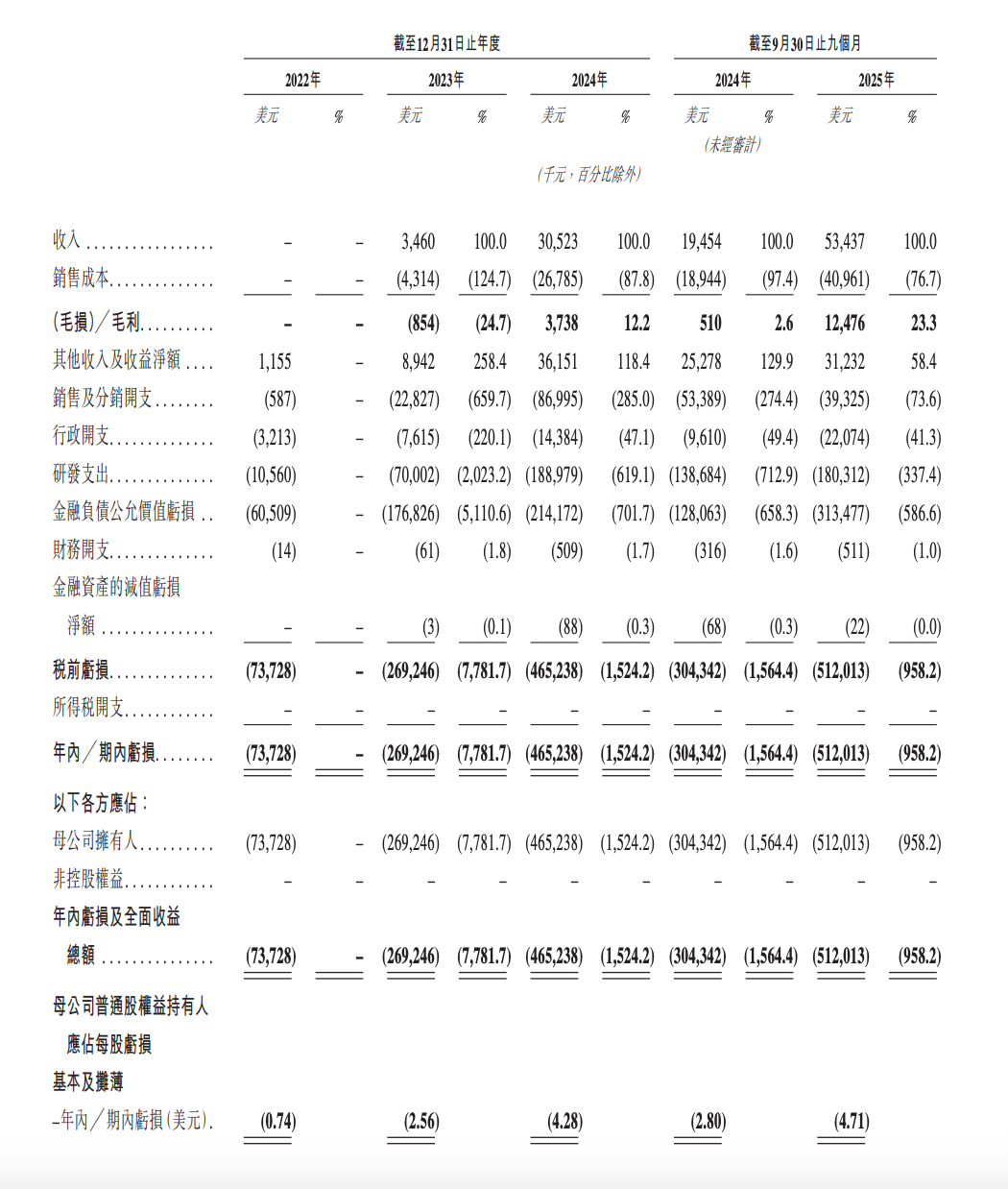

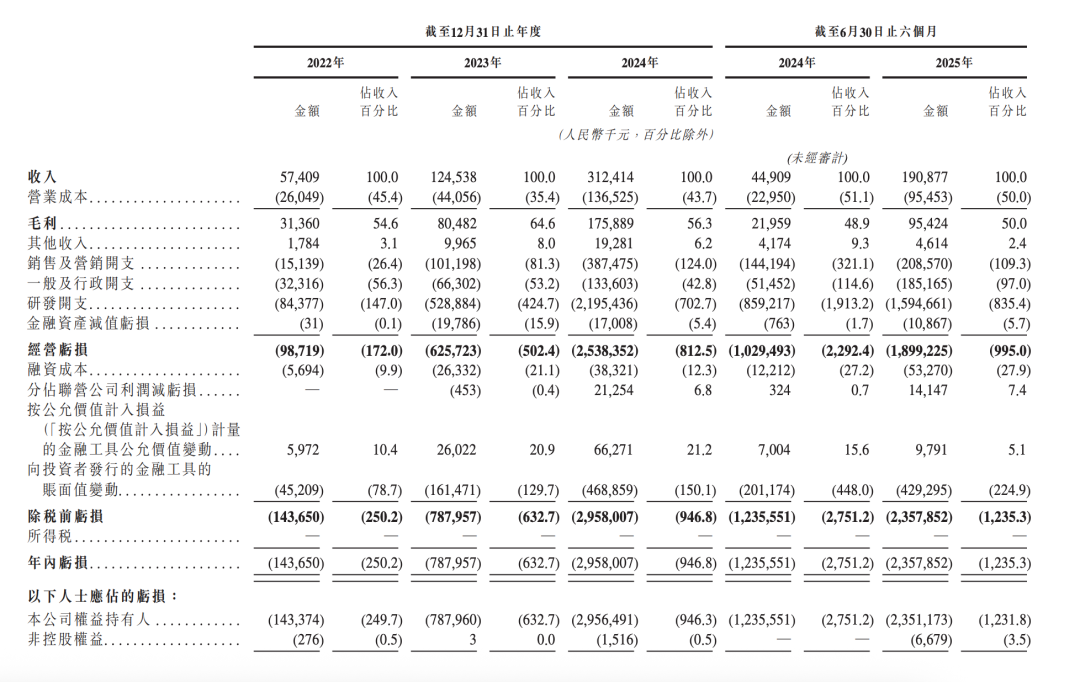

This pressure is particularly evident in the two listed companies. Zhipu's R&D expenditures grew from RMB 84.4 million in 2022 to RMB 2.195 billion in 2024, with R&D spending in the first half of 2025 exceeding eight times the revenue for the same period.

MiniMax's R&D spending also increased rapidly, from US$54.36 million in 2023 to US$185 million in 2024, and US$221 million in the first nine months of 2025. The most intuitive (intuitive) comparison is that MiniMax's R&D investment in 2024 was approximately six times its annual revenue.

However, their revenues do not correlate proportionally. Therefore, what large model companies truly need is a capital structure capable of supporting "long-term heavy investment."

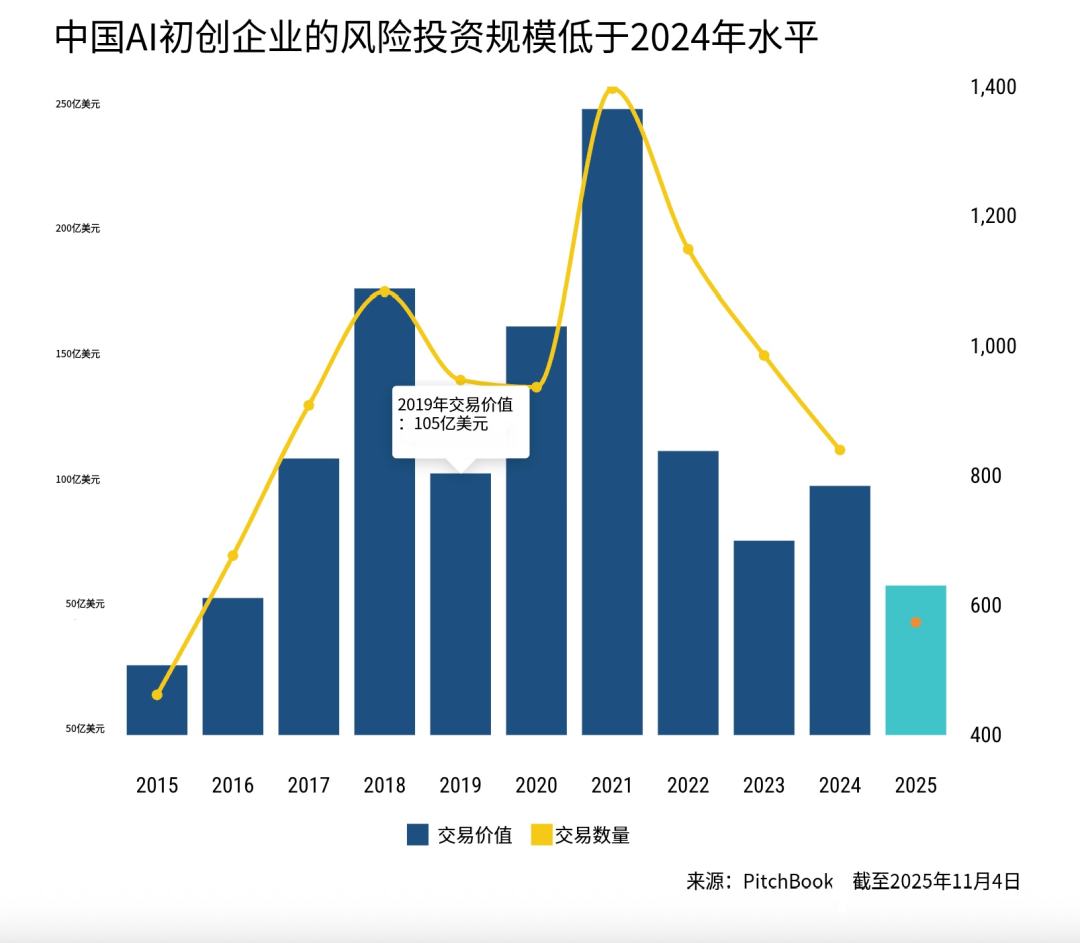

This shift is not only driven by the development needs of large models themselves but also because the previous approach of relying on successive rounds of VC financing has become increasingly difficult.

GlobalData shows that in the first eight months of 2025, total VC financing in China declined by 36% year-on-year, with a significant reduction in large-scale funding rounds. Investors now prefer smaller, higher-certainty projects. PitchBook's November 2025 report also noted a marked decline in foreign investment activity in the AI sector in Greater China. With less capital available and a preference for stability, the cost and conditions for relying on private financing to sustain operations have become increasingly stringent.

More critically, head-to-head competition is accelerating. Model iterations are speeding up, enterprise clients are moving from pilots to scalability, and compute costs continue to rise. Without securing long-term capital early, companies may be forced to reduce investment when financing windows tighten, missing critical iteration rhythms. For large model companies, delaying listings may not be more stable but could carry greater risks.

A clear path of cyclical transition has emerged: in the early stages, large model vendors relied on VC funding to showcase technological possibilities; in the mid-stage, they turned to industrial capital to demonstrate scenario implementation; today, they need public markets to provide a long-term runway.

Overall, the foundational model sector has shifted from a "universal trial phase" to a "head-to-head Decisive battle period (decisive battle phase)," but the technology is not yet fully mature, commercialization must accelerate, and capital has become more selective. In this tight spot, continuing to rely on successive rounds of private financing is challenging. Turning to public markets has become a realistic path for leading players, and the "IPO window" has thus opened at this juncture.

II. Why Has the Hong Kong Stock Market Become the Main Battleground for AI?

The involvement of public markets brings not only changes in funding sources but also an upgrade in scrutiny. Cash flow conditions, compliance systems, information disclosure, and business models are all subject to continuous evaluation.

However, the reality is that large model companies generally exhibit high investment and high uncertainty.

MiniMax's R&D spending also increased rapidly, reaching US$10.6 million in 2022, US$70 million in 2023, US$18.9 million in 2024, and US$18.03 million in the first three quarters of 2025, totaling approximately US$120 million in R&D investment.

Examining its business model, MiniMax's revenue primarily comes from subscriptions, virtual goods, and online marketing, with core products including Talkie and Hailuo AI. This type of content-interactive income is highly dependent on platform ecosystems and regulatory environments. Any changes in regulatory standards could affect the stability of its business model. In its prospectus, the company explicitly disclosed potential risks of copyright litigation related to generated content and the need to meet chatbot disclosure and compliance requirements in markets like the United States.

High investment and high uncertainty are also evident in Zhipu's case.

In terms of revenue, Zhipu generated RMB 57.4 million, RMB 124.5 million, and RMB 312.4 million from 2022 to 2024, respectively. However, R&D and compute costs are rigid and difficult to fully cover with revenue in the short term. The result is a continuously expand (continuously widening) loss, with a net loss of approximately RMB 100 million in the first half of 2024, increasing to approximately RMB 190 million in the first half of 2025, and a rising net debt scale.

Viewing MiniMax and Zhipu together, MiniMax is growing faster but relies more on content ecosystems and faces greater regulatory variables. Zhipu follows a path closer to government and enterprise infrastructure, with heavy investment and slow returns. Overall, while their commercialization paths are not yet mature, they have begun to take shape—not without revenue, but not yet substantial enough.

As the "vanguards" in the current large model landscape, they are also the most typical representatives of "high R&D, long cycles, and uncertain returns." What these companies need is not a low-threshold market but an institutional environment capable of tolerating current losses and understanding long-term uncertainties—one that allows them to prove commercialization over a longer period without being constrained by single-dimensional profit metrics.

The Hong Kong Stock Exchange's "18C" mechanism for specialized technology companies, established in recent years, provides precisely this type of tiered framework. The rules distinguish companies based on whether they meet commercialization revenue thresholds. Commercialized companies must demonstrate at least HK$250 million in revenue in the most recent audited fiscal year, while companies still in the investment phase and not yet meeting this threshold are also allowed to enter public markets. Such arrangements explicitly incorporate the financing logic of long-term technological engineering into the rules and preserve flexibility for companies in high-investment phases.

In contrast, the A-share market, particularly the STAR Market, leans more toward hard technology companies with clear industrialization paths and direct revenue scale requirements. For example, some criteria mandate annual revenues of no less than RMB 500 million in the most recent year.

As a result, the Hong Kong stock market has naturally become the main battleground for large model vendors under the new AI narrative. Judging by the listing trends of the past two years, AI companies specializing in foundational models, compute chips, and enterprise-grade large model applications are clearly flocking to list in Hong Kong, with unprecedented concentration in both quantity and type.

Overall, large model companies are flocking to the Hong Kong stock market not because the "threshold is low" but because they need a "runway" that can tolerate their current losses and accept future high uncertainties—one that also provides them with valuation and narrative space comparable to global peers. The Hong Kong stock market is precisely the most suitable in terms of institutional and environmental alignment.

III. Revisiting the AI Industry Chain Under Changing Capital Structures

Often, changes in capital structures can influence industrial landscapes even earlier than technological breakthroughs.

Going public provides not just one-time financing but a more stable "blood transfusion mechanism," enabling model companies to plan compute investments, model iterations, and team expansions over three-to-five-year cycles for the first time.

Notably, with a longer time horizon, R&D approaches evolve. Foundational model training, multimodal expansion, and agent system construction are all inherently capital-intensive and slow-feedback endeavors. If financial pressure constantly looms, teams naturally prioritize short-term, explainable routes, where parameter scale and benchmark rankings often matter more than efficiency.

With more stable cash flows, competition logic shifts toward how much compute power and data can translate into genuine intelligence improvements. The industry moves from "who can scale faster" to "who can use resources more efficiently," with efficiency replacing scale as the core variable in the next stage.

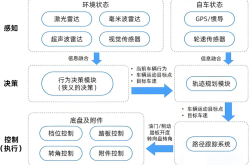

A stabilized R&D rhythm also alters the role of model companies within the industry chain.

With sustained disclosure, compliance constraints, and financial transparency, model companies become more like reliable long-term technology providers. Government and enterprise clients, as well as Cross border cooperation partners (multinational partners), will no longer assess risks solely based on technical demonstrations and short-term contracts but will view model companies as potential long-term infrastructure nodes for collaboration.

More critically, this signal rapidly transmits upstream. Over the past year, the core challenge for domestic GPU manufacturers, compute service providers, and data center vendors has not been insufficient demand but unstable demand. Projects are plentiful but short-lived, leaving risks in capacity expansion and deep adaptation. When model companies demonstrate sustained investment capabilities, upstream providers no longer see isolated orders but long-term compute consumption curves. Decisions on whether to expand capacity in advance, optimize hardware and software (software and hardware) around specific model ecosystems, or align R&D resources with particular technological paths become calculable.

When compute resources are no longer fully occupied by delivery and emergency needs, model companies gain the bandwidth to experiment more systematically with architectures, training methods, and inference strategies. The industry begins to focus more on efficiency, scalability during the inference phase, and co-design (collaborative design) between models and underlying infrastructure, rather than solely relying on larger parameters and more cards.

Such changes can only occur under relatively stable funding and rhythms.

The same logic applies downstream. For clients in finance, manufacturing, energy, government, and other sectors, "whether to dare use domestic models" has never been purely a technical issue but a risk issue. If model vendors remain in a state of financing uncertainty, enterprises will naturally relegate them to edge scenarios or non-core systems. Only when these companies enter public markets, with improved financial and governance transparency and clearer sustainable operation capabilities, will industry clients consider deeper integration, embedding models into production scheduling, risk control, design, and decision-making chains.

Meanwhile, changes in application forms are also raising industry barriers. As models evolve from conversational tools to Agents, systems begin to execute tasks, invoke tools, and influence real-world environments over longer timeframes. At this stage, risks are no longer confined to content but also involve behavioral boundaries and responsibility allocation.

It is not hard to see that the continuous constraints of the open market will, to some extent, become an implicit prerequisite for entering these key scenarios.

From a broader perspective, the wave of listings in early 2026 does not simply open a financing window but also heralds a new mode of industrial operation. Model companies gain sustained investment capabilities, upstream players secure long-term order expectations, and downstream players acquire more controllable technology partners. The industrial chain begins to shift from trial phases to a collaborative stage centered around long-term capacity building.

Of course, this does not mean the outcome is already determined. Whether technical approaches are viable, whether efficiency improvements can be realized, and whether business models can sustain ongoing investments will all be repeatedly tested over longer cycles. But at least at this moment, the listings of MiniMax and Zhipu have sent a clear signal: the competition for large models in China is entering a phase where patience, capital, and engineering capabilities collectively shape the game.