A Fatal Misjudgment: Why Did Meta Abandon Eye Tracking and Cripple Its Own Capabilities?

![]() 01/23 2026

01/23 2026

![]() 556

556

In 2014, Mark Zuckerberg splurged $2 billion to acquire Oculus VR, believing that 'virtual reality will become the cornerstone of personal computing's future.'

Fast forward to 2026, and VR has indeed begun to take root with technologies like OpenXR and Flatpak. Google, Valve, and Apple have all rolled out updates for their VR headset operating systems—with one common feature: eye tracking as a core capability. Valve focuses on gaming experiences; Google leverages its Android APK ecosystem for rapid expansion; Apple uses it to create entirely new ways of interacting with sports broadcasts and television. VR is gradually becoming the 'ultimate display interface' for next-generation human-computer interaction.

But at this critical juncture, Meta suddenly announced massive layoffs, seen by the outside world as the most dramatic 'U-turn' in its VR strategy history. Some even began to predict doom: 'Oculus was nothing but a 'legendary misjudgment,'' and 'VR is dead again.'

Yet the reality is far from that. The real issue lies with Meta itself: Over the past decade, except for the Quest Pro, nearly all consumer-grade headsets and smart glasses have lacked a crucial technology: eye tracking.

This may seem like a minor detail, but it determines whether VR can truly achieve scale. So why does the absence of eye tracking limit VR's scalability? And how did Zuckerberg's obsession with a new type of social network obscure Oculus' original vision?

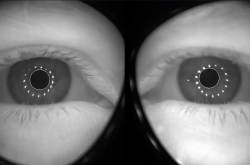

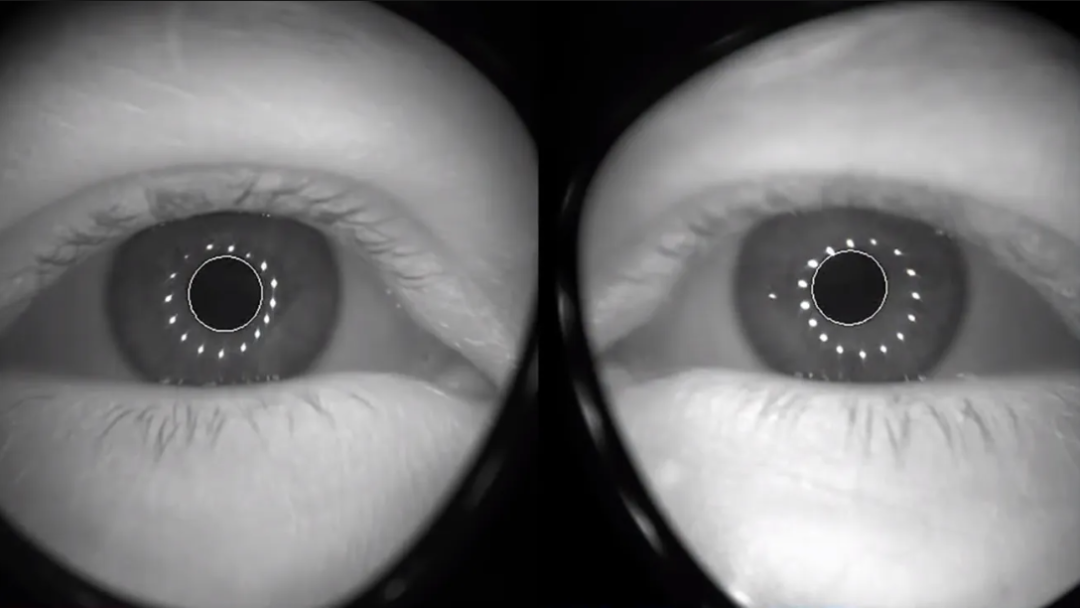

The 2017 Revelation: Eye Tracking's 'Superpower'

Back in 2017 at the Game Developers Conference (GDC), Ian Hamilton of UploadVR experienced an eye-tracking demo at Valve's booth. At that moment, he realized: 'This technology will give VR developers a 'superpower.''

In his coverage that year, he wrote:

'When games can instantly know what you're looking at and what interests you, designers' questions shift—no longer 'how to guide the player' but 'how much skill is needed to complete the task.' At that moment, I felt like I'd suddenly gained superpowers and instinctively started using them—because it was just too fun.'

Ironically, Meta spent a decade building its VR platform but never formulated a clear, coherent roadmap for implementing eye tracking. This is a classic case of 'grand long-term vision but disconnected short-term execution.'

It wasn't until 2024 that Zuckerberg casually remarked on Instagram: 'Apple's eye tracking is indeed excellent. Actually, the Quest Pro already had those sensors. We removed them from the Quest 3 but will bring them back in the future.'

This seemingly offhand comment may have been his first public admission that Meta's strategy might have been fundamentally flawed.

Why the 'Gap' After Quest Pro?

In 2022, Meta launched the high-end Quest Pro with built-in eye tracking. Logically, this should have been a turning point—much like Facebook's promise to 'stop making 3DoF devices' after discontinuing the Oculus Go. Meta should have phased out models without eye tracking.

But the reality is: As of 2026, Meta still hasn't released a second consumer-grade headset with eye tracking.

Meanwhile, Apple quickly seized the initiative with Vision Pro's eye tracking + Persona feature + FaceTime. Meta, however, bet everything on Horizon Worlds—'full-body motion capture + virtual social'—trying to attract users with the 'metaverse.'

The problem: If the system doesn't even know where you're looking, how can it understand your intent?

Existing evidence shows that VR headsets lacking eye tracking struggle to become true platform-level products. Look at the competitors: Valve, Google, and Apple's latest headsets all rely on eye-tracking technology, albeit with different focuses.

Looking back: The 2016 HTC Vive resembled Steam Frame's 'DK1,' while the 2019 Valve Index was the 'DK2.' Valve patiently refined its approach, waiting until 2026 to release a mature consumer version. Apple did the same—they believed 2024 was the optimal launch year for Vision Pro. Both depend on eye tracking for key interactions.

Valve Index

From Rift to Quest: Meta's Decade-Long March and Missteps

Zuckerberg indeed invested heavily: Starting with the acquisition of the Oculus Rift team, he recruited Valve's legendary CTO Michael Abrash and built a modern-day 'PARC' (Palo Alto Research Center) within Meta.

Early on, Meta was quite open: sharing research, incubating standout apps (like Oculus Medium, later acquired by Adobe), and once leading the industry.

But the turning point came in 2020–2021: In 2020, Facebook tried to force users to link their accounts to Quest headsets. In early 2021, it attempted to insert ads into VR, both meeting strong user backlash. Eventually, the brand was rebranded as 'Meta' in late 2021, with an independent account system.

By then, the Quest 2 was selling well, with a solid content ecosystem and near-top-tier hand tracking. The U.S. market had few competitors. Zuckerberg seized the moment to unveil his 'metaverse' vision, trying to overwrite the old narrative.

And the Quest Pro, a high-end flagship with eye tracking, was still released as planned in late 2022.

'Epic Misjudgment'? Carmack Warned Early

Meta's former CTO John Carmack had warned as early as 2021: 'The metaverse is a honeypot trap for 'architecture astronauts.' Zuckerberg wants to build it now, but after years and thousands of people, he might end up with something no one uses. We must focus on actual products, not technological fantasies.'

Former Meta CTO John Carmack

In 2022, Carmack left Meta due to 'frustration with the struggle (internal struggles).' Four years later, thousands of employees were laid off due to the company's failed VR/AR transition. The 2026 layoffs finally exposed Meta's strategic missteps, echoing the 'scent of failure' Carmack had warned about.

More worrying: Meta laid off many game development teams, betting everything on Horizon Worlds. Hits like Beat Saber and Population: One seem to serve as 'blood transfusions' to keep Horizon alive.

Even in December 2025, when the first Steam Frame dev kits reached developers, Meta removed Population: One from Steam, claiming to 'prevent PC players from exploiting openness to ruin the multiplayer experience.' This move felt more like building walls than fostering an ecosystem.

The true 'epic misjudgment' may be the entire Horizon Worlds project: forcing social networking into immature technology at the wrong time, in the wrong way.

In 2026, Meta is clearly 'resetting.' But the question remains: Which point in the timeline must it revisit to identify the root cause? What structural changes are needed to truly correct its course?

Acquiring Game Studios vs. Betting on Eye Tracking

Meta's choices have been intriguing.

After acquiring Beat Saber in November 2019, it doubled down on gaming content, recruiting developers familiar with Oculus Touch controllers. This strategy was boosted by the pandemic—a surge in home entertainment created a brief 'golden window.'

But meanwhile, the industry was already exploring deeper interaction revolutions. From 2016–2018, NextVR live-streamed NBA games to VR headsets; startup Spaces launched a Terminator VR walking experience, with consumer-grade eye tracking taking shape.

Apple's 2024 Vision Pro was the culmination of all these technologies from the past decade.

Apple Vision Pro

In contrast, Meta decided to keep selling the Quest 3, Quest 3S, and even Ray-Ban smart glasses without eye tracking after launching the Quest Pro.

Whether due to cost, production, or strategy, this decision likely explains why Meta gradually lost the first-mover advantage it gained from acquiring Oculus in 2014.

To recover, Meta poached a key Apple executive in late 2025, but was it too late?

Now, Apple, Google, Samsung, and Valve are all releasing or planning VR headsets with eye tracking, while Meta may shift to increasing non-VR glasses production.

From Reality to Virtuality, and Back Again

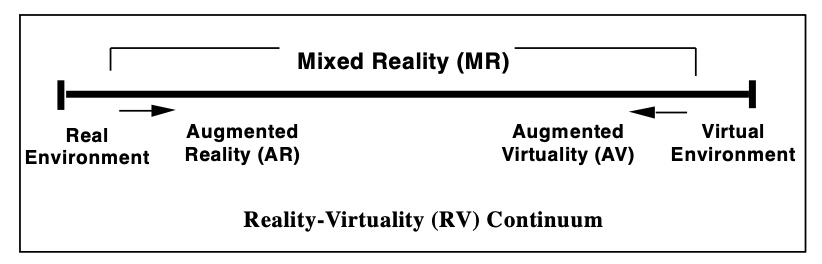

This diagram comes from Paul Milgram's classic 1994 paper, 'The Reality-Virtuality Continuum.' Thirty years later, Apple uses a dial to let you seamlessly switch between 'fully real' and 'fully virtual.'

Apple's Vision Pro is heavy and expensive, but its software defaults to the 'real world.' Turn the dial, and virtual content gradually overlays—this is true mastery of the continuum.

Meta? The Quest 3 and Ray-Ban glasses sit at opposite ends of the continuum but both lack eye tracking. This means the system can't 'read' your gaze intent, whether you're immersed in VR or wearing lightweight glasses to view the world.

Are Cameras Pointed the Right Way?

If Vision Pro is a 'spatial computer,' then Apple's counterpart to Meta's Ray-Ban glasses might be a 'spatial mouse'—no display, all input.

Imagine: A lightweight, transparent pair of glasses with hand + eye-tracking sensors on par with Vision Pro, connecting via Bluetooth to your iPad, Apple TV, or Mac.

Glance at a movie on your iPad while washing dishes, and lift your eyes to pause playback without smudging the screen;

Swipe your finger on any surface to use it as a trackpad;

Turn any plane into an input interface.

This sounds magical but isn't technologically far-fetched. Google even claimed in late 2024: 'Within two years, touch input on any surface will be solved.' Under this design logic, display-less glasses become more universal—they don't replace screens but act as a 'universal remote' for interacting with all screens.

In Vision Pro, eye tracking isn't just for menu selection; it drives Persona avatars, external screen gaze rendering, and even social presence. Apple invested heavily in 'full immersion,' but unless you experienced the thrill of becoming a superhero in VR in 2017, these features may not feel essential to average users.

So Why Is Eye Tracking Indispensable?

The answer is simple: Gaze is always the first signal of intent. Like the mouse for computers, it's a foundational interaction method. In the graphical interface era, the mouse lets you tell the computer 'I want to click here'; in VR, eye tracking lets you tell the system 'I'm looking there,' even if final actions require gestures or controller confirmation.

Conclusion of VRAR Planet:

The key to success in technological strategy often lies in the technical details that are 'present but unused' and 'absent before one realizes their importance.'

Eye tracking in VR is akin to touchscreens in smartphones—it has never been a mere 'flashy feature,' but rather the key to reshaping human-machine interaction.

Meta, with its first-mover advantage through Oculus, missed a crucial piece of the puzzle due to strategic vacillation, short-term interests, and an excessive focus on social networking.

The decision-making puzzles within this context may be more worthy of our deep contemplation than any VR experience.

Note: This article is compiled and integrated based on the original work by Ian Hamilton of UploadVR, with polishing and rewriting by VRAR Planet.

Original Link: Eye Tracking Is The Missing Piece In Mark Zuckerberg's VR Strategy (uploadvr.com)

Written by / Vivi

Images not labeled in the text are sourced from the internet