The "Army of Ants" Faces Hurdles in Promoting Healthy Afu

![]() 01/30 2026

01/30 2026

![]() 356

356

Download Afu and Secure Membership?

Author | Wang Tiemei

Editor | Gu Nian

'From encountering various advertisements in elevators and subway stations to falling victim to a scam when purchasing a membership, Ant Afu's promotional tactics seem to be everywhere.' After being deceived into buying a membership service, Zhang Xing expressed his dissatisfaction.

The "membership" that Zhang Xing mentioned refers to a type of诱导性 (inducive) link that has recently surfaced on multiple e-commerce and content platforms. These links typically entice users to buy virtual goods, such as video memberships, website memberships, or data packages, at extremely low prices—sometimes as low as a few cents or even 0.01 yuan. Users are then guided through a series of steps to "claim" these offers.

These steps often culminate in downloading the Ant Afu App, yet the promised membership benefits never materialize. According to observations by 'Shixiang,' such links have been spotted on various platforms capable of transactions, including Xiaohongshu, Xianyu, Taobao, and Bilibili, blending in with normal product links and making them difficult to spot.

The promotional chaos surrounding user acquisition is merely the tip of the iceberg. Ground promotion, often dubbed the "army of ants" in the internet realm, has never been glamorous but is undeniably effective.

In an interview with LatePost, Han Xinyi, President of Ant Group, shared a set of impressive figures: A month after Afu's rebranding, daily user inquiries doubled to 10 million, and monthly active users doubled to 30 million. He noted that health demands are not low-frequency and that feedback has been "generally positive," especially among those already aware of medical and health issues.

He further stressed, "We need to sustain this momentum and ramp up our efforts."

With escalating efforts, advertising for Afu, formerly AQ, expanded rapidly after its rebranding in December 2025. Han Xinyi admitted in the interview that "hundreds of millions" were spent in a single month, with a clear objective: to capture mindshare and continue investing in 2026 until the user base reaches a self-sustaining level.

This context sets the stage for the resurgence of ground promotion: products need to gain traction quickly but have not yet developed strong self-propagating momentum.

In Han Xinyi's vision, health products are part of "high-stakes decision-making" scenarios that cannot rely solely on celebrity endorsements or advertising blitzes but must depend on word-of-mouth diffusion. When 20%-30% of a group starts using a product, the rest are likely to follow. The challenge lies in the vacuum period before "word-of-mouth" takes effect.

Ground promotion fills this void. From early tactics like "Scan the code to receive eggs" and "Register and receive free phone bills" to today's "0.01 yuan memberships," "welfare redirects," and "task claims," the forms evolve, but the underlying logic remains the same.

Manufacture a click at an extremely low cost; leverage human density for installations. In this system, ground promotion resembles an army of ants relocating—individual actions may seem insignificant, but collectively, they can swiftly fill every ecological niche: e-commerce platforms, content communities, secondhand trading zones, comment sections, and private message inlets.

The "army of ants" brings people "in" but bears no responsibility for whether they stay, trust, or even identify with the product. When user acquisition goals overshadow product boundaries, promotion naturally distorts: from introduction to inducement; from traffic diversion to trust erosion.

01 Online and Offline Synergy

"What I don't understand is why Afu, an Alibaba product, needs to resort to such promotion tactics," Zhang Xing expressed his confusion to 'Shixiang' after being scammed. Needing temporary access to a Baidu Netdisk membership, Zhang opted to look for low-cost daily rental services on e-commerce platforms.

"You could say I was being frugal, but I'd done this before without issues—this was the first time I got scammed," he said. He spotted a 4-yuan "one-day Netdisk membership" link on Xiaohongshu, which automatically dropped to 0.01 yuan upon clicking. Thinking it was a platform discount, he proceeded to pay. The customer service then sent a "membership claim tutorial."

"Everything seemed normal at first," Zhang recounted, until he opened the tutorial image and noticed something amiss. The tutorial instructed him to download Alipay, save a QR code, and scan it with Alipay. Scanning redirected him to Ant Afu's download page and required logging in with an Alipay account. Subsequently, he had to send his "order number" to Afu customer service to claim the membership.

Upon seeing the download link, Zhang grew wary. After searching on Xiaohongshu, he discovered numerous similar cases where users followed instructions but never received memberships. Such scams had proliferated across Xiaohongshu, Bilibili, Taobao, Xianyu, and other platforms.

These links often masquerade as Netdisk, video memberships, or data packages, initially lowering defenses with reasonable pricing before slashing prices to extremely low levels after clicking, exploiting the consumer's "bargain-hunting" mentality to secure payments. Even if discovered later, the worst outcome is a refund or a reported link, making the deception cost exceedingly low.

Throughout this process, the QR code that needed to be saved and scanned with Alipay became a pivotal link—referred to as the "exclusive code" by ground promotion service providers.

"Only a few get high cashback codes; most are just 'harvested garlic chives,'" the provider remarked, adding that Afu's current ground promotion situation is a "necessity." Originally, this exclusive code was intended for offline ground promotion.

A service provider involved in Ant Afu's ground promotion revealed that promotion has now shifted to a "person-to-person" model: ground promoters no longer rely solely on their teams but expand reach by recruiting "learners."

The method involves providing learners with so-called "exclusive codes," offering a 2-10 yuan cashback for each new user download facilitated through the code. To obtain high-cashback exclusive codes, learners must pay tens of yuan in "tuition" to ground promoters.

"Take the common 'scan for eggs' example—downloading via scanning is manageable, but the biggest issue arises at the 'Alipay authorization login' step. People now associate Alipay with their wallet, and for users, it's an unfamiliar app. Requiring Alipay login upfront makes them heavily defensive."

Additionally, Afu's ground promotion counts valid data by requiring new users' real names and information and having Afu ask three questions.

During offline promotion, some service providers, to complete tasks swiftly, use users' phones to ask questions directly, then photograph user information—even Alipay interfaces. Such irregular operations have significantly increased user alertness. "I didn't expect Alipay's endorsement, which should be an advantage, to become a disadvantage," one provider lamented.

Ant CEO Han Xinyi summarized Afu's strengths as professionalism, automation, and personalization when elaborating on its advantages. Yet, under the layered ground promotion tactics, leaving a professional first impression with users may be challenging.

He also emphasized that Afu is a product that "understands users better the more it's used," meaning it requires real user interaction data to train models and optimize services. The ground promotion task of requiring new users to ask three questions via Afu aims to initiate data collection.

However, in actual ground promotion, with task completion as the sole metric, many users report that promoters directly input meaningless questions to meet system requirements swiftly. This not only diminishes user trust but also transforms data collection—meant to understand real user needs—into meaningless mechanical interactions.

02 Afu Is Not Yu'ebao

From the service provider's perspective, Afu, backed by Alibaba and endorsed by He Jiong, should face fewer promotion hurdles. Yet, in actual offline promotion, his perception was shattered. The provider told 'Shixiang' that promoting Afu is even more challenging than for some obscure small apps.

"Though backed by Alibaba, Afu can't offer clear 'download-and-get' benefits, the biggest challenge in ground promotion," the provider explained. The "download-and-get" benefit is essentially immediate value realization on the spot.

In the mobile internet era, this is the core of offline promotion's effectiveness. For instance, Didi's early online ride-hailing required no waiting, and subsidies reduced fares to 0.1 yuan—even cheaper than public transport. By offering targeted, immediately perceivable benefits to specific groups, many products achieved zero-to-one growth.

For Afu, offline ground promoters struggle to identify clear user benefits. Zhang Junjie, Ant Group's VP and Health Business Group President, stated that Afu is positioned as an "AI health friend," aiming to provide Q&A, companionship, and care. The vision is grand and high-end, but in ground promotion's instant communication, it remains abstract.

Some providers admitted that when asked, "What does this App do?" they couldn't provide a concise, intuitive answer. One summarized: "In offline promotion, users hear 'AI health manager' and immediately dismiss you. Later, we found online channels reach users already familiar with AI products."

Clearly, ground promotion logic faces entirely different challenges in the AI era. Mobile internet ground promotion relied on clear tool value or instant incentives to move users offline to online. AI products aim to create new interaction scenarios and long-term companionship—values that cannot be quickly conveyed through "incentives."

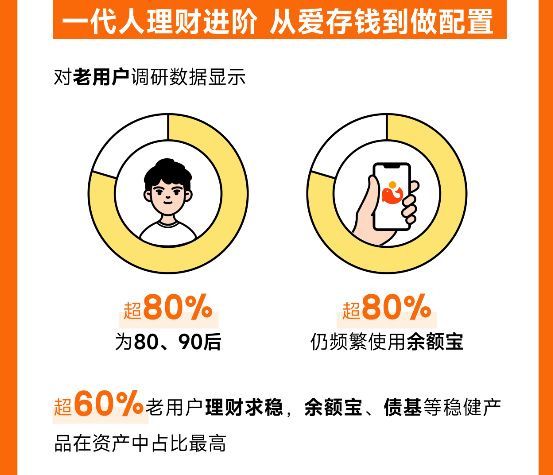

Of course, Ant Group has product genes that don't rely on ground promotion. For example, Yu'ebao, also under Ant, gained over 1 million users within six days of launch and surpassed the combined customer base of China's top 10 money market funds by day 18.

Its viral success relied on the "1 yuan minimum purchase, redeemable anytime" model and Alipay App accessibility, rewriting wealth management's trajectory and setting a template for digital financial services.

With dual functions of financial management and payment, zero fees, and low thresholds, Yu'ebao reached 185.3 billion yuan in scale and 43.03 million users by the end of 2013, creating a money market fund miracle. In just six months, it ignited internet wealth management's development, sparking financial awareness and practice among countless Chinese.

However, Afu hasn't found the early mobile internet ground promotion incentives or Yu'ebao-level product design genes to drive user adoption. Awakening Chinese people's proactive health awareness clearly can't be solved by merely labeling it an AI health assistant.

03 Ant's Ambitious Saturation Investment

To outsiders, Afu's promotion resembles a massive market blitz; internally at Ant, it's a KPI-driven top priority.

In an interview, Ant CEO Han Xinyi stated that Afu's promotion has invested hundreds of millions and won't cease, with the core goal of capturing mindshare. "In health, we must win. We have strategic resolve and investment guarantees and will continue saturation investment this year."

The saturation of human, material, and financial resources likely extends fully to the outermost execution layer—ground promotion service providers and networks.

Multiple providers told 'Shixiang' that after factoring in tiered rewards and cashback subsidies, the peak cost per "effective user" acquisition may far exceed typical Apps. High subsidies aren't rare, but without adequate oversight, they quickly become another driver of ground promotion chaos.

The "person-to-person" viral mechanism providers mentioned further amplifies this incentive distortion, layering risks. In practice, mid-level providers build highly ad-hoc promotion networks by recruiting "learners" and distributing "exclusive codes."

Top-tier incentive promises inflate during transmission, while costs and risks press down on the lowest-tier promoters. To recoup "tuition" and earn cashbacks swiftly, bottom-tier promoters often simplify processes, use vague language, or directly deceive users.

When complaints or disputes arise, they're dismissed as "individual promoters' violations." Moral hazards shift smoothly to a highly mobile "gig worker" group, minimizing violation costs. The worst outcome is link removal—negligible compared to cashback gains from deceptive downloads.

One provider recalled encountering a college student user well-versed in Alibaba's ecosystem and AI. The user complied with downloads and questions but immediately deleted the app afterward.

The reason was direct: providing health information to AI and generating personal health profiles might risk privacy leaks and even affect future commercial insurance underwriting and costs. "He wasn't worried about Alipay's security but was very cautious about Ant Afu's privacy boundaries," the provider said. "Honestly, I thought his concerns made sense."

Reviewing the industry's development, whether internet healthcare business models hold remains a recurring question. As Han Xinyi acknowledged, healthcare is typically high-value, low-frequency, and its service unit prices are highly regulated. Compared to e-commerce or food delivery, customer acquisition and operational costs remain prohibitively high, making scale effects extremely difficult to achieve.

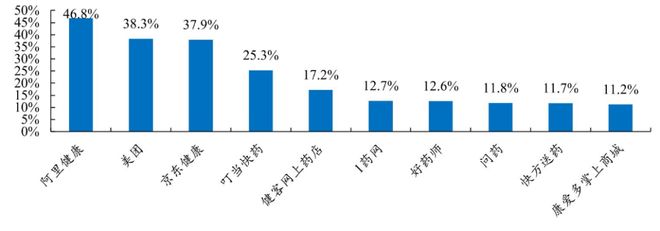

This process is slow, heavy, and difficult, testing patience immensely. Whether Alibaba Health or JD Health, their pharmaceutical e-commerce self-operated businesses contribute over 80% of revenue in recent years. Online consultations primarily serve as electronic prescription and traffic entry points—essentially still a "medicine-supports-healthcare" model.

This model is both practical and effective; however, it diverges from the original vision of internet healthcare, which was to "enhance the accessibility of medical services." The advent of AI has reignited the aspirations of major tech companies to redefine this domain. Consequently, the "medicine-insurance-healthcare" closed loop has emerged as the new cornerstone of a comprehensive health ecosystem.

Ant Group's core strength now resides in its distinctive "payment + finance + insurance" ecosystem.

By 2025, Ant Group's complete acquisition of Haodafu is poised to breathe new life into its accumulated medical resources through the integration of financial and insurance capabilities. Alipay's extensive user base and high level of trust provide natural channels for access, while platforms such as Ant Insurance offer pre-existing scenarios for "medicine-insurance integration."

Theoretically, Ant Group could even construct a comprehensive data network that encompasses health consultations, medical examination reports, exercise data, insurance applications, and claims. This network would serve as the foundation for personalized health management and the innovation of insurance products.

When questioned by the media, "What if Afu fails?" Han Xinyi responded with a determined strategic outlook, stating, "In the past, there was a possibility of failure with Alipay and Yu'ebao, but we did not approach the issue from that perspective. We will ensure Afu's success."

He underscored that Ant Group has been laying a digital foundation in healthcare for over a decade. The Afu Q&A platform adheres to a "clean and ad-free" policy. If Afu cannot achieve success, then it will be equally difficult for other companies in the entire healthcare AI-to-Consumer sector. Given the resources, patience, and determination involved, this is virtually a "must-win" battle.

However, precisely because of this, any erosion of trust at the outermost layer will be amplified infinitely. This is also the most crucial aspect for Ant Group to remain vigilant about when deploying its "army of ants" to achieve its AI-driven healthcare objectives.