Scavenging Leftovers and Leeching off the Wealthy! Is Oracle Fighting for Survival?

![]() 01/23 2026

01/23 2026

![]() 480

480

Previously, Dolphin Research covered CoreWeave, a small leader in the new cloud era of AI, as a shadow case study for analyzing the U.S. IaaS industry. This time, we turn our attention to a far more influential new cloud player—Oracle, one of OpenAI's current primary partners.

As the inaugural coverage piece, Dolphin Research will focus on the following questions:

1) Provide a concise overview of Oracle's development history, tracing how a 50-year-old company evolved into a new cloud services powerhouse.

2) Clarify Oracle's business and revenue composition, identifying key drivers impacting its performance.

3) Analyze the 'tipping point'—what the $300 billion deal signifies and where it originates.

4) After replacing Microsoft as OpenAI's primary partner, what has Oracle gained and lost? What motivates this high-stakes gamble, and what are its implications?

Below is a detailed analysis.

I. The Past and Present of a 50-Year-Old Company

1.1 Development History: From Databases to Enterprise Management Software to Cloud

As an introduction, let's briefly review how Oracle, a '50-year-old company,' transitioned from a traditional software firm to a leading AI cloud giant, now second only to the three major players, with significant market and industry influence:

a. Database Era (1977–1990s): In its early years, Oracle's business was relatively singular, focusing on database management systems, primarily relational databases (RDBMS) paired with SQL retrieval (as seen today). This laid the foundation for databases as Oracle's core and strongest business, gradually making it the market leader in the U.S. database industry.

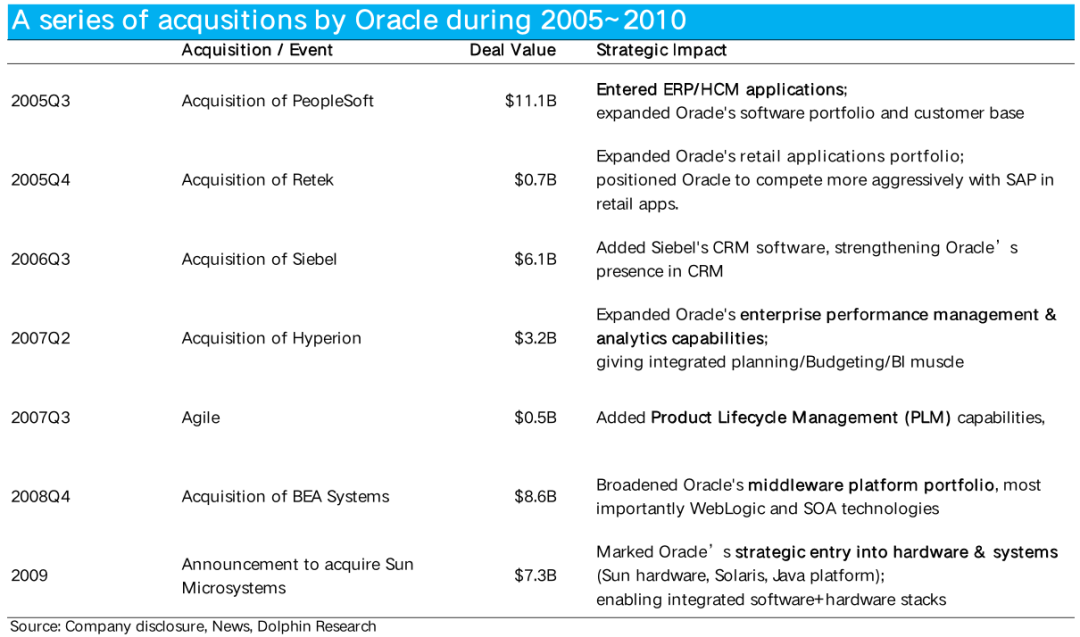

b. Diversification—Software First, Then Hardware (1990s–2009): After establishing a foothold in its core database business, Oracle began diversifying in the 1990s.

First, it entered the enterprise management software sector, including ERP (resource management), CRM (customer relations), HCM (human resources), and other management tools. During the early diversification phase (1990s–2000), Oracle primarily relied on internal development, creating prototypes for future products like Oracle E-Business Suite.

However, from 2003–2009 (after recovering from the dot-com bubble), the company shifted to external acquisitions, strategically buying leading companies in each enterprise software segment (see table below for details).

Through these acquisitions, Oracle rapidly strengthened its technological capabilities and business scale in enterprise management software, becoming the second-largest player after SAP.

The final major acquisition in this phase—Sun Microsystems—helped Oracle further expand from software services into hardware and operating systems.

c. Integration Era (2010–2015): After acquiring Sun in 2010, Oracle shifted its focus to integrating and streamlining its various businesses, both organic and acquired. It evolved from offering standalone services to providing comprehensive solutions spanning underlying hardware to end-user applications.

By this point, Oracle had largely completed its vertical integration, covering hardware, foundational software services (e.g., databases and operating systems), and end-user applications.

d. Early Cloud Transition Struggles (2012–2022): Amid the broader industry shift from traditional on-premise software to cloud, Oracle was initially skeptical, only belatedly starting its cloud transition in 2012.

Oracle's cloud journey unfolded in two phases. The first began in 2012 with the SaaSification of its software services, launching Oracle Cloud Application (OCA).

It also introduced early IaaS services (Cloud 1.0), but due to technological lag, these failed to gain market traction.

The second phase started in 2016 with the launch of a ground-up rebuilt Cloud 2.0, later known as Oracle Cloud Infrastructure (OCI). This included Bare Metal services and integrated its flagship Autonomous Database into OCI, marking its true entry into the IaaS cloud services sector.

However, OCI's early progress was sluggish. By FY2022 (ending May 2022), cloud revenue (SaaS + IaaS) accounted for just 25% of total revenue, with OCI contributing only ~7%. It remained a minor player in the cloud services industry.

e. New Cloud Era in AI (2023–Present): Only by late 2022 (FY2023) did Oracle's OCI business begin to grow rapidly, fueled by the AI boom's surge in computing demand.

The September 2025 announcement of a $300 billion order from OpenAI and other clients catapulted Oracle into a central role in the AI + cloud services ecosystem and investment narrative.

(Note: In early FY2023, Oracle made a major acquisition—Cerner, a leading healthcare software company—boosting total revenue by ~14% and accelerating growth that year. Excluding this impact, organic revenue growth remained low single-digit.)

1.2 IaaS Business—OCI: The 'Biggest' and 'Only' Bright Spot

Above, we briefly recounted Oracle's transformation from a traditional database and software company to one of the most closely watched cloud services providers today.

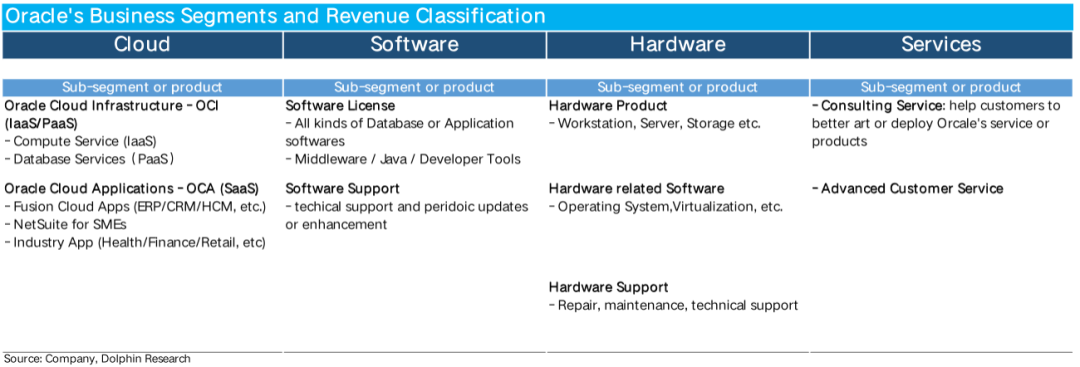

With cloud becoming Oracle's primary revenue growth engine, starting in FY2026 (August 2025), Oracle adjusted its revenue/business segment disclosures.

The key change: previously, cloud and software businesses were reported together in the same segment, with some overlap. Now, cloud is separated into a standalone segment—clearly divided into four segments: Cloud, Software, Hardware, and Services—to provide clearer visibility into its cloud business growth.

Based on these four segments, here's a brief overview of Oracle's business composition:

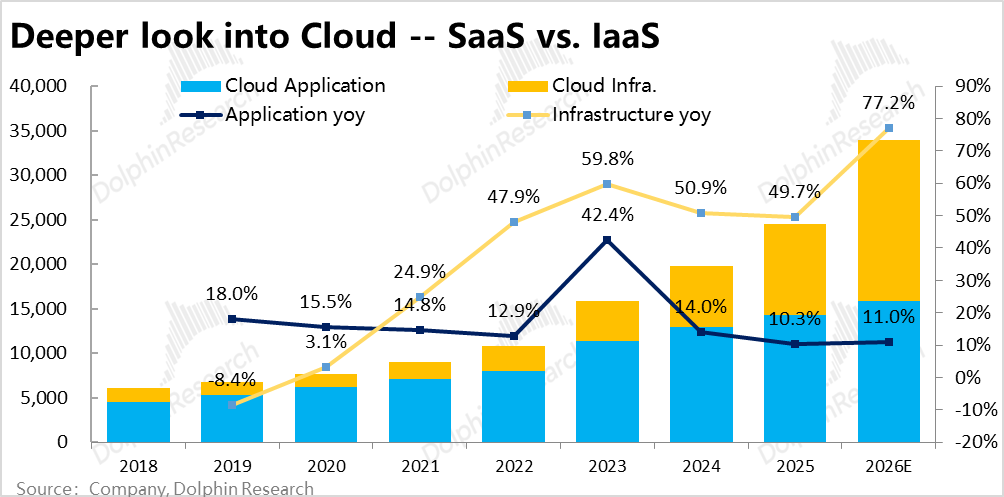

a. Cloud Business: Currently the most critical segment, further divided into IaaS (OCI) and SaaS (OCA) lines.

OCA primarily includes SaaS-based ERP/CRM/HCM and other general management tools, along with some vertical industry tools. OCI focuses on Oracle's unique database services and computing power leasing.

Historically, OCA held a larger share (70–80%) of the cloud segment, but OCI's share has gradually surpassed OCA due to rapid growth in the past 1–2 years.

b. Software: Traditional on-premise software deployed and managed by customers. Once Oracle's largest revenue segment, it has now been overtaken by cloud (falling from over 60% to under 40%).

It comprises two main parts: one-time software license sales and recurring service/support revenue (e.g., usage support and maintenance updates).

Service revenue is typically 3–4x larger than license sales.

c. Hardware: Similar to software, it includes one-time hardware (e.g., servers) sales and recurring maintenance/support revenue. It accounts for the smallest share, now around 5%.

d. Services: Other non-hardware/software services, mainly consulting on efficient deployment and utilization of Oracle's offerings or custom services. Recent annual revenue share is in the high single digits.

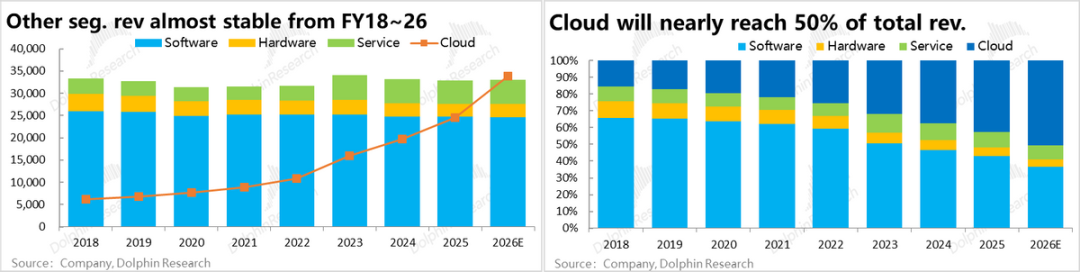

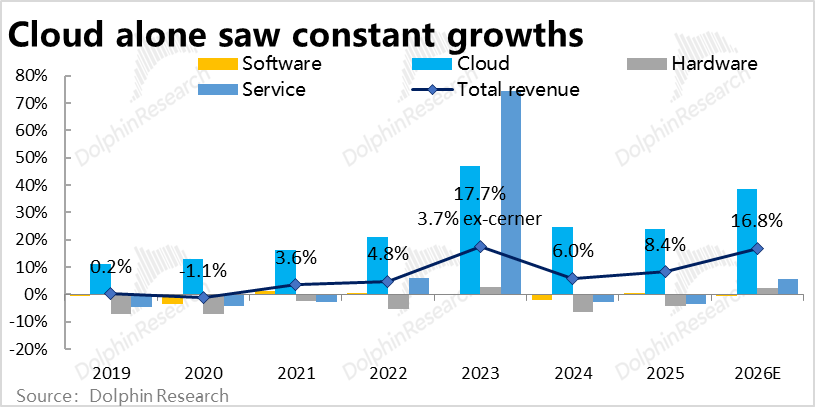

Based on the FY2026 classification, we reclassified Oracle's historical revenue. Revenue growth by segment from FY2018 to FY2026 (forecast) shows:

a. Since FY2018, Oracle's non-cloud traditional businesses (software, hardware, and services) have stagnated, often even contracting (including post-AI boom).

Annual revenue has hovered between $30–35 billion over nine years. Dragged down by traditional businesses, total revenue growth remained low single-digit from FY2018–2024 (excluding acquisition impacts in FY2023).

b. Cloud has been Oracle's sole revenue growth driver in recent years, contributing over half of total revenue in FY2026 and becoming its largest and fastest-growing core business.

c. Further, OCA, the larger cloud segment historically, has seen relatively weak growth (<20%) since FY2018 and has been decelerating (except in FY2023 due to acquisitions), dragging down overall cloud growth.

The true driver of Oracle's cloud and total revenue growth is OCI under IaaS. As shown below, OCI's revenue growth has consistently stayed near 50% or higher since FY2022.

With OCI rapidly scaling and surpassing OCA, it has propelled overall cloud and corporate revenue growth. Driven by AI demand and OpenAI partnership, OCI is poised for continued high growth.

II. The Decisive Factor—OCI

From the review, it's clear that Oracle's traditional core business—software—has been declining for years, while its SaaS cloud business has seen modest growth. Oracle now relies almost entirely on its IaaS business (OCI) for growth.

Thus, all subsequent analysis will focus on the latest developments in Oracle's cloud business (especially OCI), with minimal discussion of traditional businesses.

2.1 Tipping Point—The $300 Billion Mega-Order

Studying Oracle inevitably leads to the 'earthquake' announcement at its F1Q26 earnings call—a staggering ~$300 billion in new demand contracts signed that quarter, equivalent to 5.8x FY2025 total revenue or nearly 2.4x the remaining performance obligations (RPO) of $138 billion as of F4Q25.

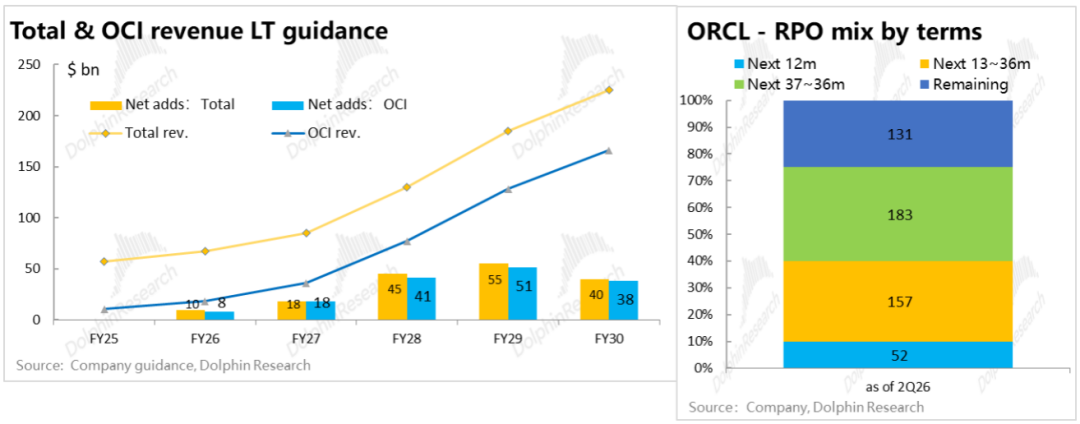

Oracle also provided rare multi-year guidance through FY2030, later revised upward in analyst calls. Current guidance:

a. Total Revenue: Growing from ~$57 billion in FY2025 to $225 billion in FY2030, a 31% CAGR over five years.

b. OCI Revenue: OCI, the core driver, will grow from ~$10 billion in FY2025 to $166 billion in FY2030, a ~16x increase over five years, with a noticeable acceleration starting in FY2028.

c. OCI Remains the Sole Driver: Combining these points, OCI will contribute 90–100% of the annual net revenue increase from FY2027–2030.

In other words, not only in the past but also in the foreseeable future, Oracle's growth will depend almost entirely on OCI. This suggests Oracle expects minimal growth from SaaS and non-cloud businesses during the guidance period.

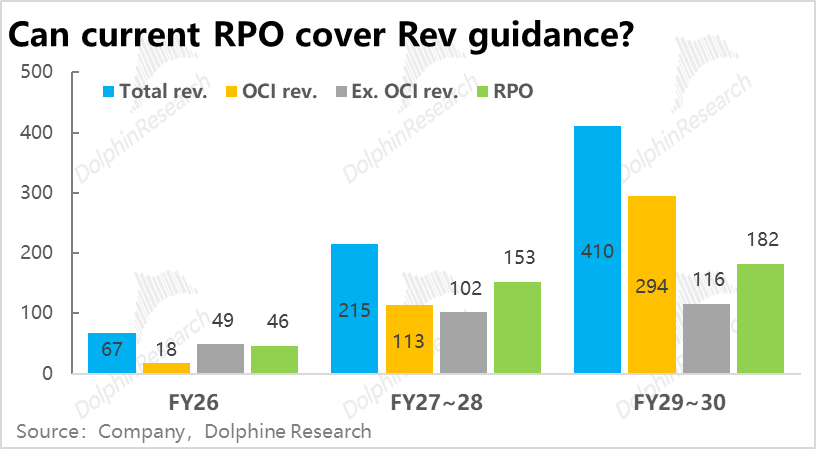

The latest RPO (remaining performance obligations) to be recognized over different periods (next 12 months, 13–24 months, etc.) roughly aligns with revenue guidance for FY2026, FY2027–2028, and FY2029–2030, showing:

a. Oracle mentioned Cloud RPO now accounts for ~95% of total RPO. Given guidance that SaaS-based OCA revenue won't grow significantly, RPO beyond 12 months can be roughly attributed to OCI.

b. For FY2026–2028, expected OCI revenue is fully covered by existing RPO, indicating high certainty.

However, post-FY2029, current RPO covers only ~62% of expected OCI revenue, leaving a ~$110 billion gap over two years. This implies Oracle must secure more large orders to meet current guidance (suggesting strong confidence in its future prospects).

2.2 Where does the Hundred-Billion Contract Come From?

So where does this 'sudden' $300 billion+ order come from? The simple answer is that the market currently consensus is that the vast majority of this large order still comes from a single client, OpenAI. A more detailed look:

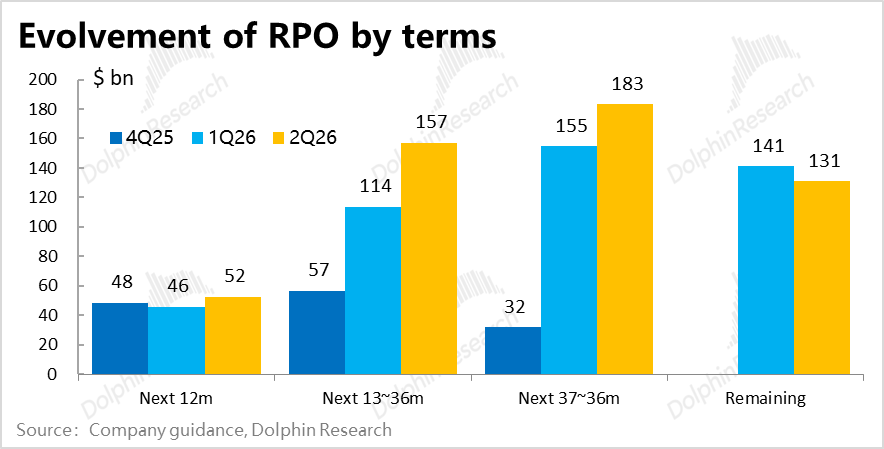

a. Expectations for a Hundred-Billion-Dollar Order Were Already There: Prior to the 1Q26 earnings announcement, Oracle had already announced a cloud services order with a certain client, starting from FY28 (mid-2027 in the calendar year), worth approximately $30 billion annually. However, the contract duration and total amount were not disclosed.

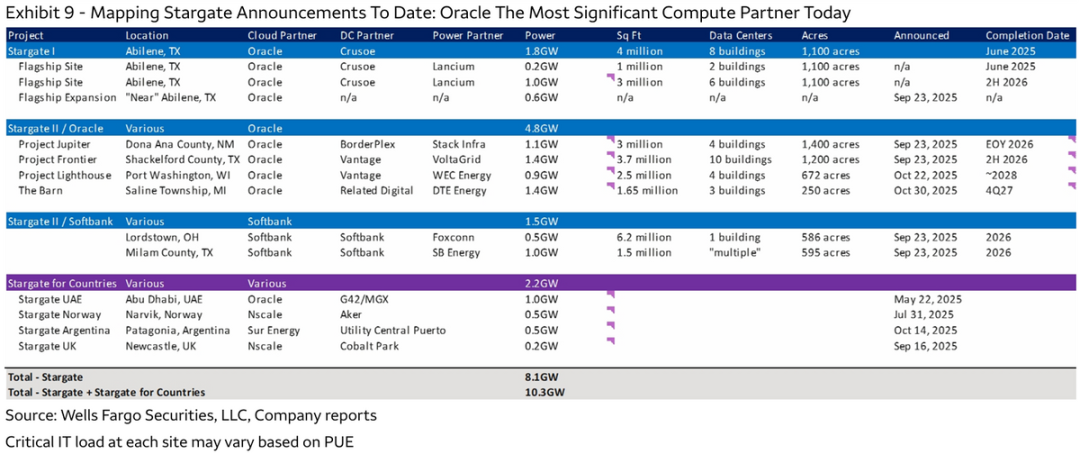

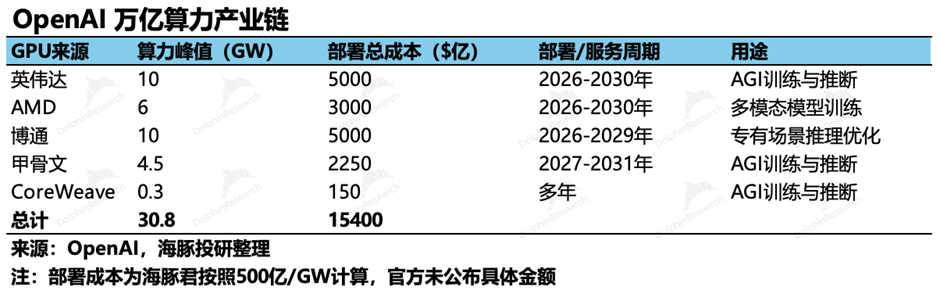

Combined with OpenAI's announcement on July 22nd of a new batch of computing power supply agreements with Oracle under the Stargate framework, adding approximately 4.5GW of capacity—namely, the four projects in Stargate II listed in the table below—the market believes that this annual $30 billion order corresponds to the Stargate II project. Assuming a five-year contract period, it was expected that RPO would increase by approximately $150 billion quarter-over-quarter in F1Q26.

b. Actual Order Size Doubles: Contrary to expectations, the actual quarter-over-quarter increase in RPO during 1Q26 was over $300 billion, double the initially anticipated amount.

This greatly exceeded everyone's expectations but also raised a new question: Where did the extra $150 billion order come from? Since the company's official statement in the F1Q26 announcement was that 'the new orders this quarter came from three different clients,' the market once attempted to identify the other two major clients besides OpenAI but found no success.

Currently, the market understands that the vast majority of the $300 billion+ order still comes from OpenAI alone. The difference now is that the cloud services contract actually signed between OpenAI and Oracle is worth $60 billion annually, spanning five years starting from the natural year 2027.

Therefore, in simple terms, the net increase in RPO doubling from $150 billion to $300 billion is likely not because Oracle found other clients comparable in size to OpenAI, but rather because the scale of OpenAI's order doubled compared to the previously announced amount.

2.3 A 'Substitute' for Microsoft and a Larger Version of CoreWeave?

1) Replacing Microsoft as OpenAI's Largest Partner

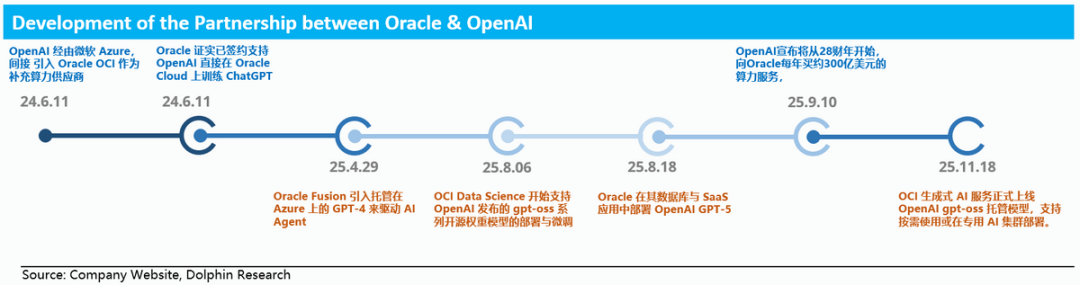

Signs of cooperation between OpenAI and Oracle have been evident for a long time. In June 2024 (when Microsoft still held the exclusive right to provide computing power to OpenAI), Oracle had already acted as a 'subcontractor' to supply computing power to OpenAI through Microsoft, the 'prime contractor.' (Similarly, Microsoft had previously outsourced some of its demand to CoreWeave due to supply constraints.)

In January 2025, Microsoft and OpenAI renegotiated their contract, with Microsoft voluntarily relinquishing its exclusive right to supply computing power to OpenAI. Essentially, Microsoft was unwilling to bear the risks of excessive client concentration and overinvestment in OpenAI's 'dreams.' Subsequently, Oracle replaced Microsoft as one of OpenAI's primary cloud service partners.

Moreover, the cooperative relationship between Oracle and OpenAI is very similar to the previous relationship between OpenAI and Microsoft. Oracle not only earns revenue by providing computing power to OpenAI but also leverages OpenAI's technological capabilities to strengthen its own weaknesses in independently developing large models.

According to reports, Oracle has also integrated OpenAI's AI capabilities into its own Fusion SaaS software and database services and can now sell pre-deployed GPT model services to clients within OCI.

2) Taking What Microsoft Doesn't Want: Is Oracle's Deal Really a Good One?

However, as the market often says, 'What Oracle gets from OpenAI is what Microsoft doesn't want'—namely, low-value business. While Oracle benefits from the massive orders and enhanced AI capabilities through its cooperation with OpenAI, it also assumes considerable risks.

From this perspective, Oracle resembles another emerging AI cloud player, CoreWeave, which we previously studied. Specifically, the potential risks include:

a. Highly Concentrated Client Base: Based on Oracle's contract volume with OpenAI at $300 billion (possibly more), it accounts for approximately 58% of the company's current total RPO. Although not as severe as CoreWeave, and with about $60 billion in new orders reportedly coming from two new clients, Meta and Nvidia, in 2Q26, the issue of client concentration remains.

b. Relatively Weak Technological Capabilities: Similar to CoreWeave, we believe Oracle's software/technological capabilities are not strong, at least compared to the traditional three major cloud providers. Therefore, its bargaining power with clients is low, or it cannot significantly improve the profitability of its business through value-added services like software.

This is evident from the fact that most of the company's current computing power leasing is in BareMetal mode; historically, the company's early IaaS services (Cloud 1.0) failed due to relatively backward technology. Before the AI wave, the growth of the company's IaaS business had been tepid; these situations all attest to this.

c. Although Better Than CoreWeave, AI Cloud Business Profit Margins Are Still Low: It is a market consensus that the profit margins of AI cloud services are generally lower than those of traditional businesses (due to the high cost of the latest GPUs and other equipment). For Oracle, with its focus on BareMetal, relatively low value-added, heavy reliance on a single client (OpenAI), and low bargaining power, the pressure on gross margins will naturally be significant.

The market once believed that Oracle's AI cloud business gross margins were less than 20% (assuming Oracle's computing power utilization rate was only 60%-90%). However, during the October investor conference, the company officially guided that the gross margins for AI cloud would be between 30%-40%. Considering CoreWeave's gross margins are approximately 25%-30%, we believe the company's guidance is generally credible.

Oracle's profit pressure in the AI cloud business is not as severe as CoreWeave's, not 'struggling at the breakeven point,' but it still represents a significant decline compared to its original gross margins of 70%-80%.

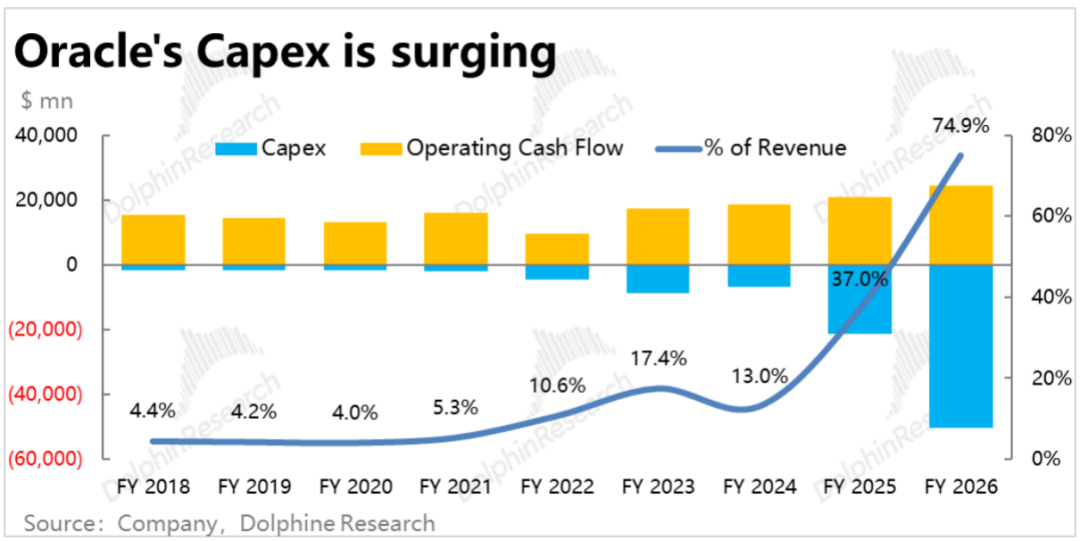

d. Significant Capex and Debt Pressure Already Exist, and the Peak Has Not Yet Been Reached: Similar to CoreWeave, the massive construction of new data centers has also imposed significant pressure on Oracle's cash flow and debt.

According to the company's latest guidance, total Capex for FY26 is expected to double to $50 billion, equivalent to 75% of the expected total revenue for the year and more than twice the expected operating cash flow. Such a huge cash flow gap will either deplete inventory cash or require bond financing.

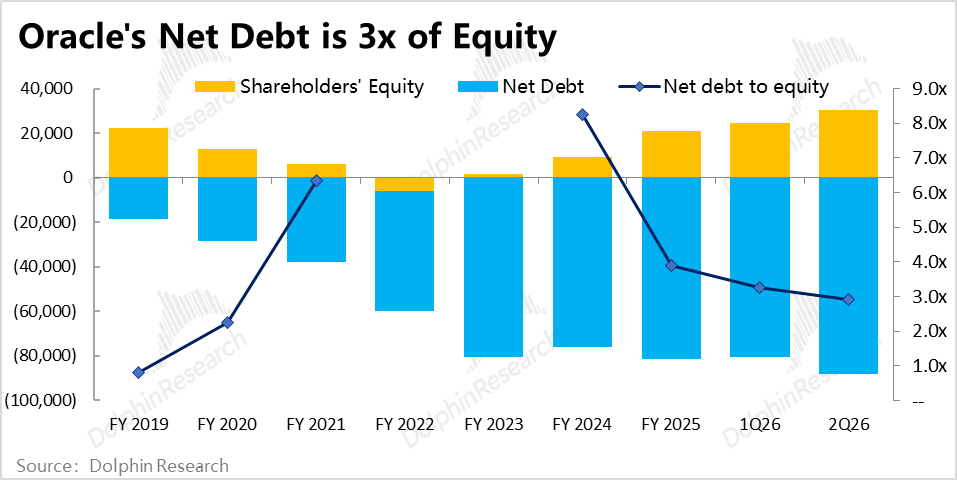

However, due to some historical reasons, the company's inventory cash is quite limited, less than $20 billion as of 2Q26, and its current net debt is nearly three times shareholder equity. The true peak of Capex and bond issuance has not even arrived yet.

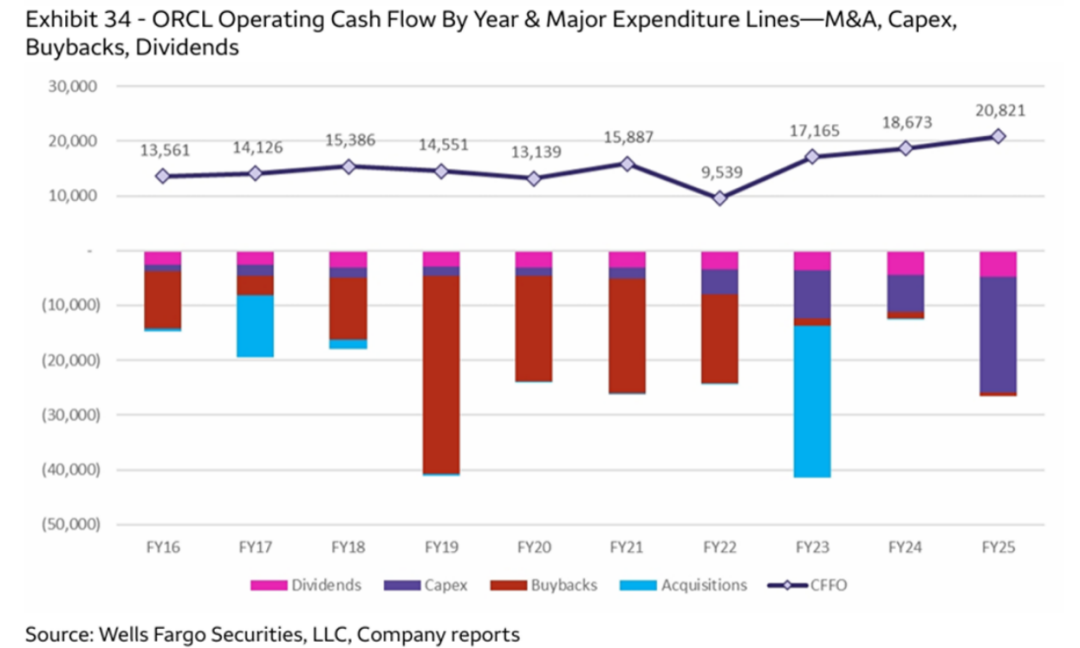

For more than a decade, Oracle has adopted a 'debt-funded operation' philosophy. As seen in the chart below, since FY16, the company's cash expenditures have almost every year exceeded its operating cash flow. In the early years, this was mainly used for massive repurchases and external acquisitions; in the future, it will primarily be used for Capex.

Moreover, as mentioned earlier, Oracle's existing data center construction plan will reach its peak production capacity starting from FY28. Therefore, the company's Capex investment peak will begin around FY27.

In other words, the real stress test for the company's cash flow gap and debt has not yet arrived, but the current balance sheet structure is already not healthy. If a black swan crisis occurs, Oracle truly risks insolvency and shareholder equity wiping out.

III. Conclusion: A Mixture of Immense Opportunities and Risks

Through the analysis in this article, Dolphin Research's key judgments about Oracle are as follows:

a. Traditional Businesses Lack Luster; OCI Is Not Just 'Icing on the Cake' but a 'Life-or-Death Gamble.' Whether judging from past performance or the company's own guidance, except for the IaaS-based OCI business, all other businesses have entered a mature or even declining phase with little to no growth. (SaaS cloud still has slight growth, while non-cloud businesses have been in negative growth for years.)

Therefore, for Oracle, OCI is not just 'icing on the cake' that would be nice to have but not critical. OCI must succeed; otherwise, the company will become a traditional software company with little to no growth, vulnerable to being overtaken by the AI revolution, and 'waiting to die.'

Because OCI means survival if successful and failure if not, Oracle is so proactive in its cooperation with OpenAI and willing to take on the enormous risk of 'overinvestment in AI computing power.'

b. A 'Larger Version of CoreWeave' with All the Associated Problems: Although Oracle is much larger than CoreWeave, its fundamental positioning is similar—a supply chain-type company tied to OpenAI's ship, doing the 'hard work.'

Highly concentrated client base, low bargaining power, and low technological value-added result in low profits in the AI business; significant Capex investment and reliance on debt financing entail the enormous risk of potential insolvency. Oracle also faces all these issues.

c. As OpenAI's New Close Ally, Significant Opportunities and Risks Exist: On the one hand, replacing Microsoft as OpenAI's primary partner brings enormous potential revenue space to the company. Even if other businesses do not grow, total revenue is expected to achieve a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of up to 31%.

On the other hand, the company's current RPO may also increase significantly further. Among the total 26GW cooperation intentions previously signed between OpenAI and chip companies such as Nvidia, AMD, and Broadcom, Oracle may 'get a share' as a cloud service operator. Additionally, the company may secure new orders from clients like Meta and xAI.

However, on the flip side, the over 30GW of computing power supply intentions already signed by OpenAI may also carry the risk of 'intentional overreporting.' The orders currently in hand may not all be fulfilled and could become 'bad debts' stuck in the company's hands.

- END -

// Republication Permission

This article is an original piece by Dolphin Research. Authorization is required for republication.

// Disclaimer and General Disclosure

This report is for general comprehensive data purposes only, intended for users of Dolphin Research and its affiliated institutions for general reading and data reference. It does not consider the specific investment objectives, investment product preferences, risk tolerance, financial status, or special needs of any individual receiving this report. Investors must consult with independent professional advisors before making investment decisions based on this report. Any person using or referring to the content or information in this report to make investment decisions does so at their own risk. Dolphin Research shall not be liable for any direct or indirect responsibilities or losses that may arise from using the data in this report. The information and data in this report are based on publicly available sources and are for reference purposes only. Dolphin Research strives for but does not guarantee the reliability, accuracy, and completeness of the information and data.

The information or opinions expressed in this report may not be used or deemed as an offer to sell securities or an invitation to buy or sell securities in any jurisdiction. They also do not constitute recommendations, inquiries, or endorsements for relevant securities or related financial instruments. The information, tools, and materials in this report are not intended for or intended to be distributed to jurisdictions where distributing, publishing, providing, or using such information, tools, and materials would violate applicable laws or regulations or result in Dolphin Research and/or its subsidiaries or affiliated companies being subject to any registration or licensing requirements in such jurisdictions, nor to citizens or residents of such jurisdictions.

This report merely reflects the personal views, insights, and analytical methods of the relevant authors and does not represent the stance of Dolphin Research and/or its affiliated institutions.

This report is produced by Dolphin Research, and the copyright is solely owned by Dolphin Research. Without the prior written consent of Dolphin Research, no institution or individual may (i) make, copy, reproduce, duplicate, forward, or distribute in any form copies or replicas, and/or (ii) directly or indirectly redistribute or transfer them to other unauthorized persons. Dolphin Research reserves all related rights.