Digging Deep into Minimax and Zhipu: Large Models - A Brutal Showdown of Computational Power Intensity and Financing Endurance?

![]() 01/27 2026

01/27 2026

![]() 551

551

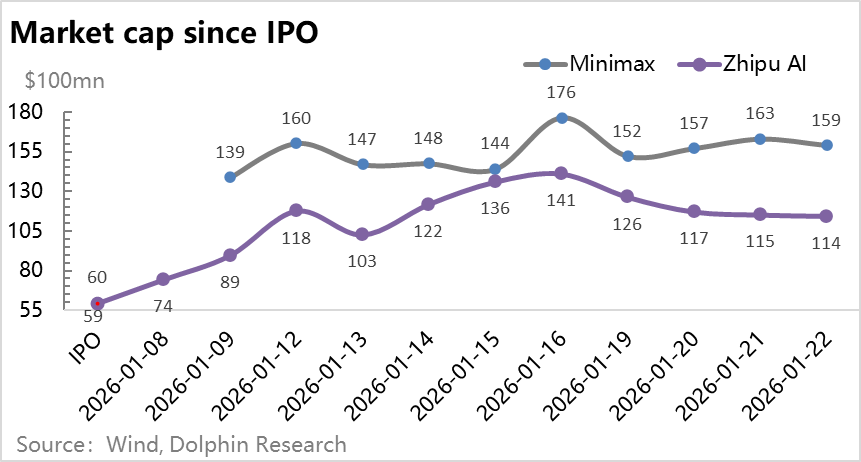

Three years after the release of ChatGPT in early 2026, two major Chinese AI large model startups, Minimax and Zhipu, went public almost simultaneously, both with valuations of approximately $6 billion. After going public, both experienced a surge, driving up the entire AI application sector. However, a closer look at the financial statements of these two large model companies reveals a relentless trend of losses.

On one hand, there is a global frenzy of price competition among large models, turning them into increasingly commoditized products. On the other hand, there is the bottomless pit of R&D investment in models, yet there are also scenarios of doubling profits. Amidst this contrast of fire and ice, Dolphin Research has long questioned the nature of the business of large models.

This time, Dolphin Research will delve into this question by analyzing data from the two listed companies:

1) What are the essential investment elements and intensity required for large models?

2) What role does computational power play?

3) How can model economics be balanced?

4) Ultimately, what is the business model of large models?

Here is a detailed analysis:

I. Soaring Revenues, Alarming Investments

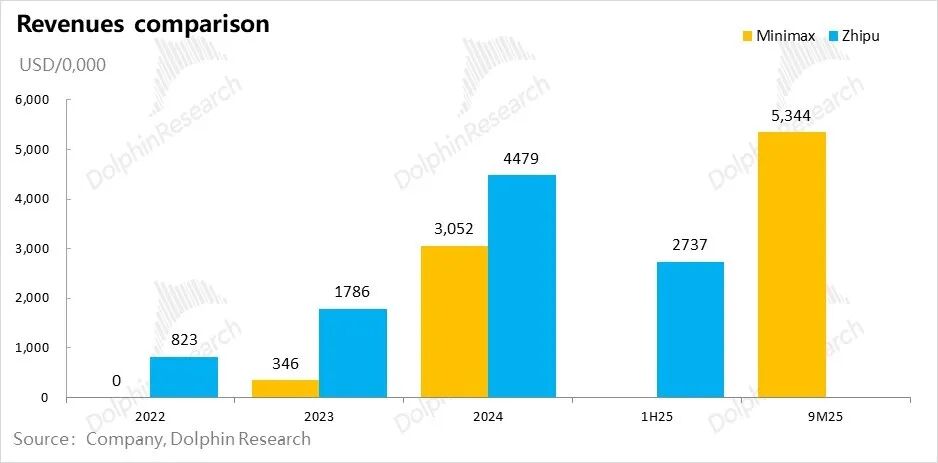

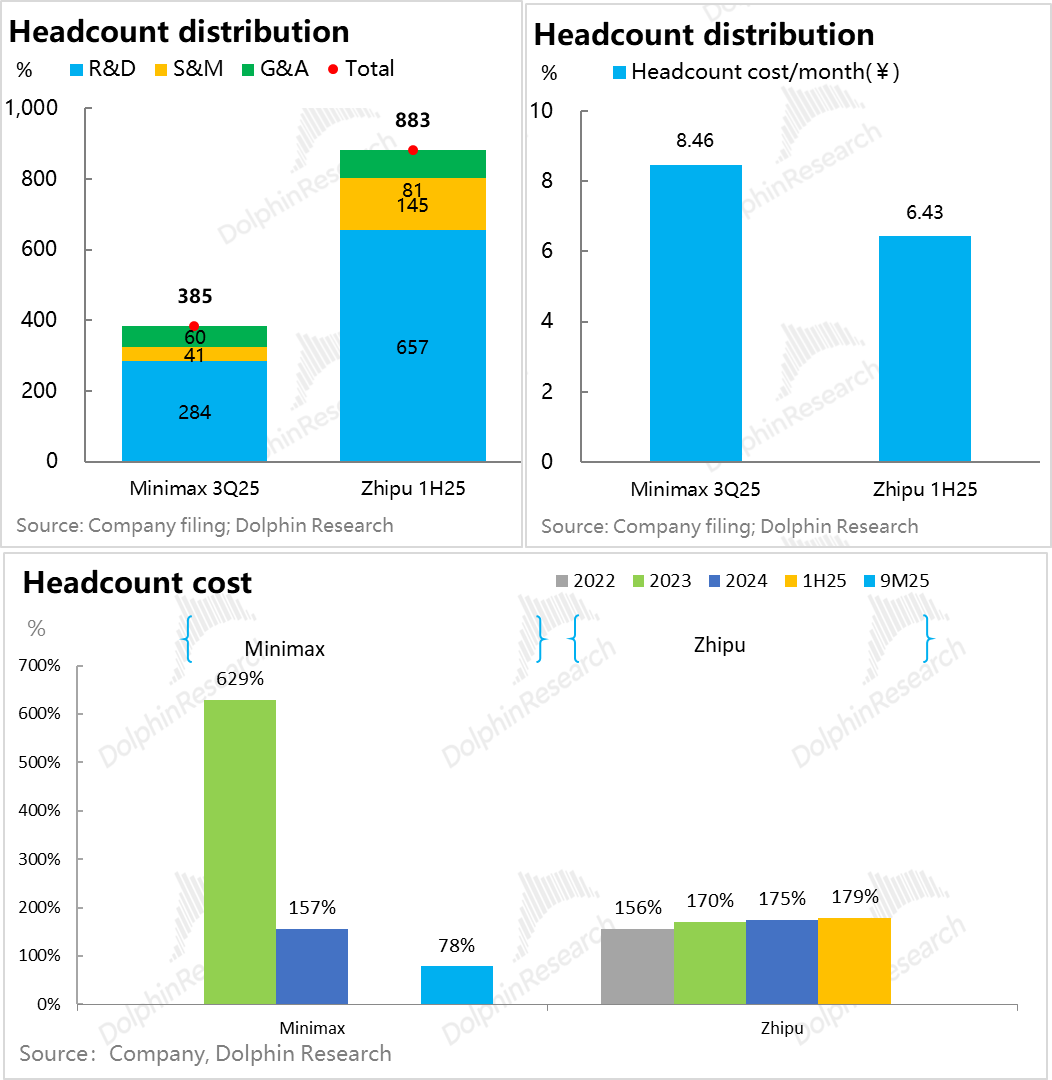

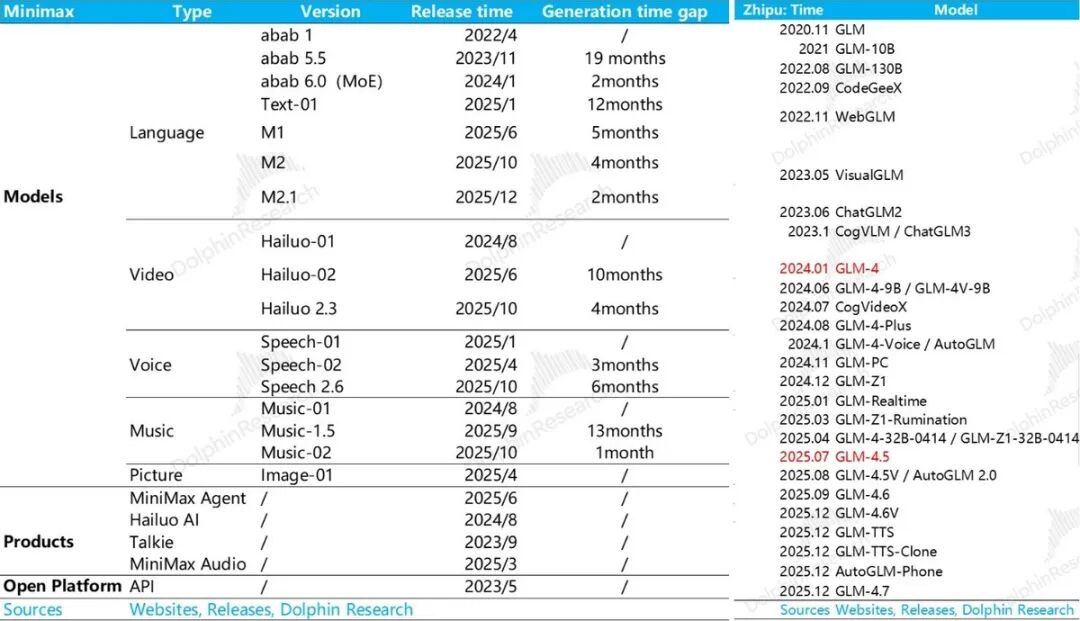

Both large model companies, Minimax and Zhipu, are "compact and powerful"—with small teams, rapid product iterations, and fast revenue growth. By the second half of 2025, their headcounts had not exceeded one thousand, starting from zero revenue, both were rapidly approaching annualized revenues of $100 million within two to three years.

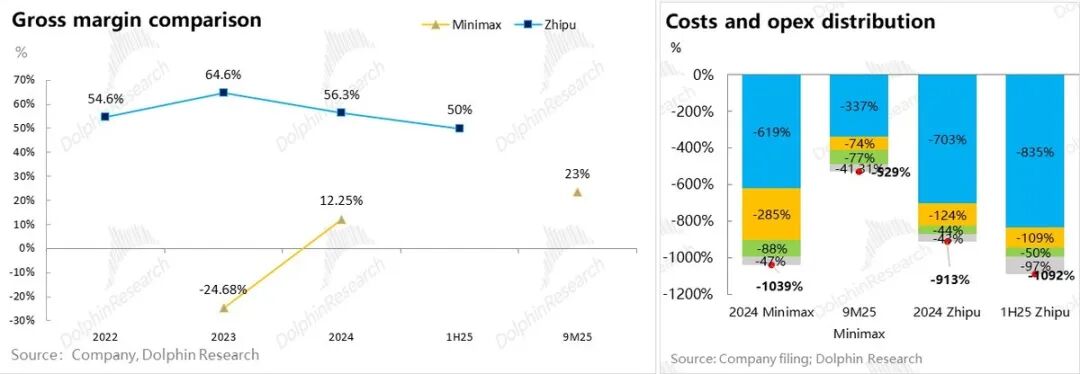

However, when it comes to expenditures, even soaring revenues pale in comparison to the aggressive investments: despite maintaining high gross margins of 50% throughout the revenue growth process for Model to B company Zhipu, or even achieving positive gross margins for Model to C company Minimax.

In 2024, the combined expenditures (costs and operating expenses) of the two companies were roughly 10 times their respective revenues. After Minimax's revenue rapidly expanded in the first nine months of 2025, expenditures remained more than five times its revenue; while Zhipu appeared even less economically scalable in the first half of 2025.

The core issue here is, for model companies, does larger revenue lead to a narrower loss rate, or does it result in a higher loss rate due to diseconomies of scale?

The three fundamental elements of model economics—data, computational power, and algorithms—are well-known. However, to determine whether models follow the scale economies of the internet, it is crucial to understand the investment intensity required for large models.

In large language model training, the specific training data used has never been truly disclosed by model developers, but there are roughly two consensus points on this issue: a. Public corpora include encyclopedias, code repositories, and the Common Crawl corpus; b. However, public and standard corpora have almost been exhausted for model training.

By 2026, large model companies have begun to rely on synthetic data and chain-of-thought data. Looking ahead, to feed models with more data, companies must either rely on their own extremely rapid deployment to access more scenarios or possess proprietary data, such as internet giants with greater data advantages. The remaining option is to compete in terms of the ability to pay for private data.

However, due to data compliance and privacy concerns, no model developer would disclose the volume of data fed in their financial statements. What truly reflects on the statements are computational power and algorithms, with algorithm advancement essentially relying on human talent and computational power corresponding to chips and cloud services. Let's examine these two aspects one by one.

II. Are Human Resources Too Expensive? Not the Core Issue!

Both companies have overall headcounts not exceeding 1,000, especially Minimax with fewer than 400 employees. In both companies, R&D personnel account for nearly 75%, with a monthly cost per head ranging from RMB 65,000 to 85,000 (excluding equity incentives), with Minimax's R&D personnel costing RMB 160,000 per month.

Due to its more streamlined team, Minimax has been able to cover its salary expenditures with revenue as its income grows. In contrast, Zhipu, primarily focusing on B2B commercialization, requires more sales personnel and places greater emphasis on general-purpose models in R&D, resulting in less significant improvement in human resource costs.

In fact, from these two companies, it can be seen that investment in human resources for large models is more about the density of talent "brainpower" rather than just headcount. Even from Minimax's talent density, it may hint at the emerging human resource structure of internet companies in the AI era:

A small but elite team of large model R&D talents, with many other departmental roles being replaced by models (Minimax offers numerous AI products but does not correspond with an excessively large headcount), resulting in an overall salary structure with extremely high per-capita salaries but generally controllable totals.

For example, Minimax's total annual salary expenditure is approximately $100 million (roughly 90% of its revenue). Considering the iterative capabilities of these two companies' foundational models, the speed of multimodal releases, and the fierce competition for talent in the overseas AI sector (where salaries for top talent can reach hundreds of millions of dollars), such personnel expenditures are not excessive.

III. Core Conflict: Revenue Generation vs. Investment—Can Balance Ever Be Achieved?

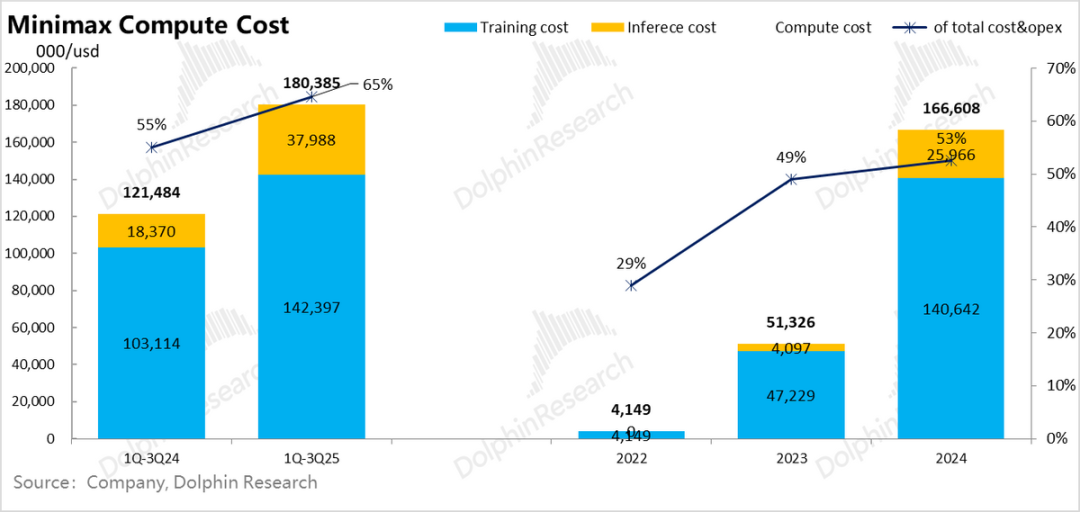

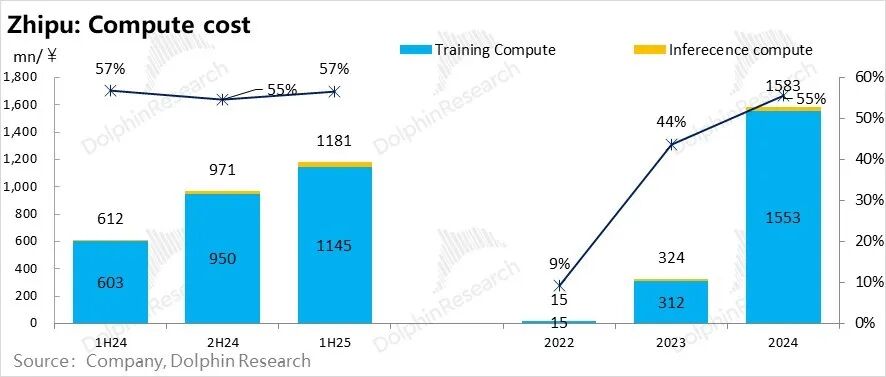

Although salary costs have largely "consumed" current revenues, compared to computational power investments, human salaries are just a small piece of the pie. Salaries can at least be effectively diluted with revenue expansion, but computational power investments, based on the current situations of these two companies, represent a type of investment with a steeper growth slope than revenue.

Moreover, from their financial statements, it is almost certain that both companies rely on third-party cloud services for their computational power due to their minimal fixed asset expenditures, adopting a relatively asset-light model rather than OpenAI's approach of highly controlled data centers.

In the financial statements of large model companies, computational power usage is divided into training computational power and inference computational power.

During the model training phase, it is equivalent to developing a commercially viable product or service, requiring R&D investment. Before the product is deployed (the model enters the inference scenario), the corresponding model training expenditures are considered "sunk costs" incurred before product launch and are recorded as R&D expenses.

Once the developed model is deployed in an inference usage scenario, the generated revenue is recorded as income, while the model's computational power consumption during the inference phase is recorded as a direct cost in the cost of goods sold.

The underlying logic is simple: large model companies invest in talent, computational power, and data to conduct model R&D in laboratories. This is a "sunk investment" that must be made regardless of whether the model is utilized by customers.

Only when the model is developed and can be used in the inference phase, whether through customer API calls or directly using the model to create apps for revenue generation, do inference revenue and inference computational costs arise.

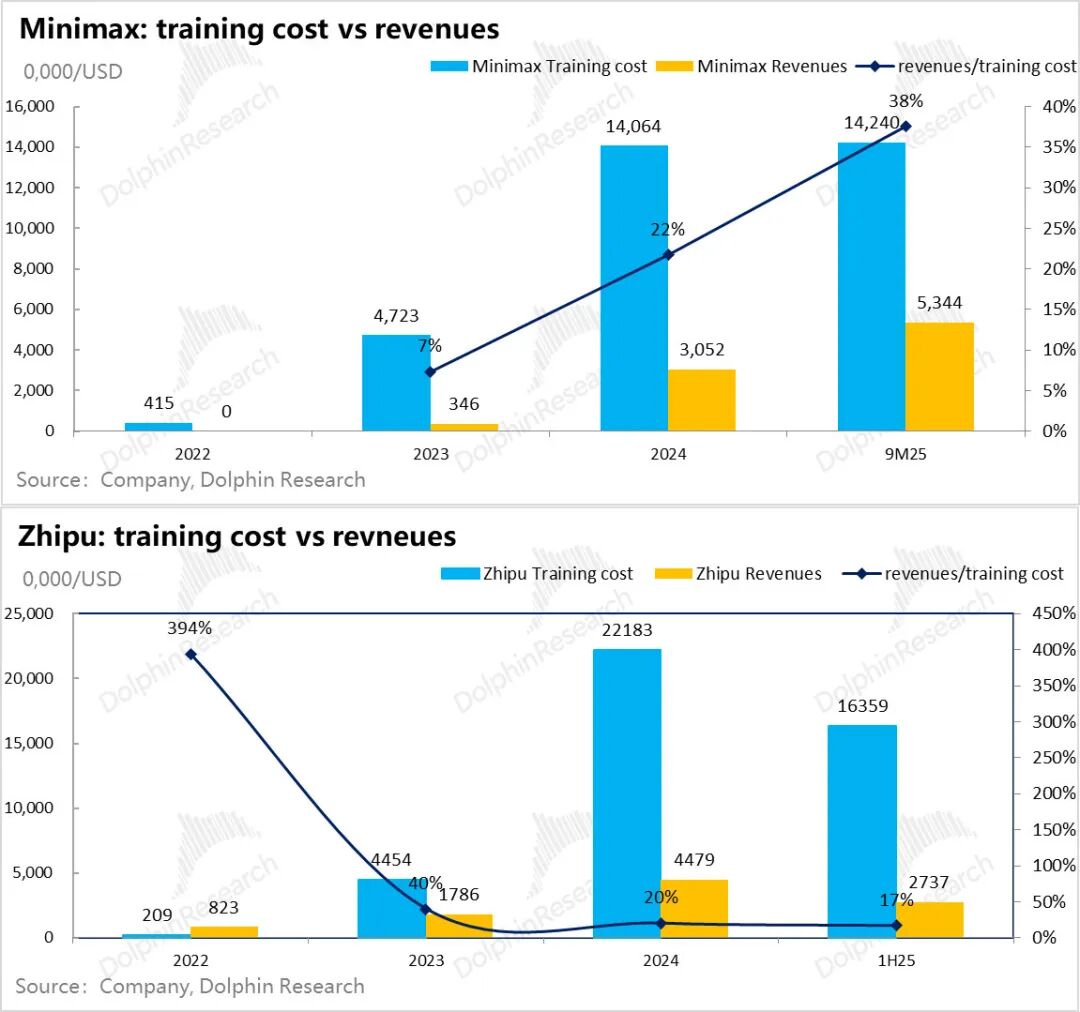

Taking Minimax and Zhipu as examples, for model R&D alone, training computational power investments account for over 50% of total expenditures, representing the absolute majority of spending and a veritable "money pit," contributing to over half of the expenditures behind their 5-10 times loss rates.

This proportion directly quantifies the claim made by Dolphin Research in "The Original Sin of the AI Bubble: Is NVIDIA an Irreplaceable 'Stimulant' for AI?" regarding computational power draining profits from the entire industrial chain.

Comparing revenue generation with model training investments further highlights the intensity of training investments:

From Minimax's perspective, revenue generated in 2024 was only 65% of the model training computational power investment made in 2023. Although revenue grew rapidly in the first three quarters of 2025, its ability to cover the training computational power costs in the same period of 2024 further decreased to 50%. Zhipu's coverage rate in the first half of 2025 was even lower at 30%.

Due to its product deployment focusing on overseas B2C emotional AI companionship, Minimax incorporates many game and internet value-added monetization models (detailed product and commercialization deployment will be analyzed separately). The internet scale effect of B2C combined with strong overseas payment capabilities results in relatively less pressure on revenue to cover training costs.

However, Zhipu faces a clear situation of high revenue growth but weakening ability to recover training costs due to the steeper growth slope of training costs.

Over the past two years, although both companies, as leading independent large model companies in China, have experienced high revenue growth slopes, the compensation of current revenue for previous R&D investments has been unsatisfactory.

The trend over the past two years shows that although both companies, as leading independent large model companies in China, have experienced high revenue growth slopes, the compensation of current revenue for previous R&D investments has been unsatisfactory.

For models to excel, training costs rise; revenue growth, no matter how fast, cannot keep pace with the escalating investments in successive generations of models. This raises the contradiction: models become increasingly loss-making. How can we understand the commercial value of such a business?

IV. What Is the Business Model of Large Models?

The staggering 1000% loss rates of large models once again vividly illustrate that their R&D is a talent-, computational power-, and data-intensive business model.

The resonance of strong investment and rapid iteration, in Dolphin Research's view, essentially transforms a capital-intensive business with a strong balance sheet into one that is entirely reflected on the income statement.

When it possesses long-term economic and commercial value, the model reverts to a true "balance sheet" business—where models no longer require annual investments, but rather, a one-year training cost can sustain revenue generation for the next 10 or even 20 years, allowing models to continuously generate income. Only at this point, when training costs can be amortized over the long term, does the true commercial basis for R&D capitalization of model training costs emerge. Specifically:

1) Computational Power: Ever-Increasing "Fixed Asset Investments"

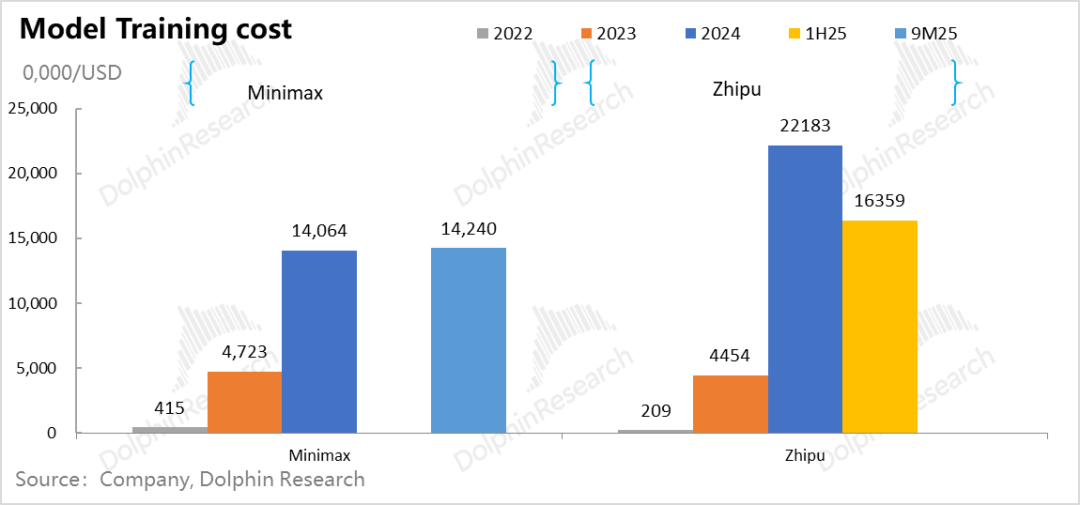

Taking Minimax and Zhipu as examples, training a model in 2023 cost between $40 million and $50 million. To achieve linear generational differences in the next model, exponential increases in data volume, model parameters, and computational power investments are required, ultimately raising the total demand for computational power despite efficiency improvements.

From these two companies, it can be seen that upgrading a model to the next generation typically increases training costs by 3-5 times.

The current competitive pace in the large model sector is roughly one new model generation per year. This means that a model trained in the previous year corresponds to only one year of inference revenue generation in the following year.

With such high computational power investments, amortization and depreciation are not feasible, and all costs must be recorded as current R&D expenses, resulting in the "dismal" loss rates exceeding revenue by 5-10 times, as mentioned earlier.

2) Rapid Iteration: Revenue vs. Investment—A Never-Ending "Cat and Mouse Game"?

Both Zhipu and Minimax face the common situation where their models' revenue-generating capabilities cannot cover their computational power investments. Although revenue growth cannot keep pace with training costs, Crazy investment (frenetic investment) while incurring heavy losses is almost an inevitable fate for large model R&D.

To survive until the dawn, companies must almost invest an additional 3-5 times their revenue in financing, considering this generation's model revenue and R&D salary expenditures, to fund the next generation's model R&D and ensure market competitiveness.

Continuing this snowball effect leads to a situation where revenue cannot keep pace with future investments, and as long as a company remains in the large model competition, it must continuously seek financing, with the financing gap widening as the company grows—a "capital competition" game.

3) Scaling Law Failure: The End of the Capital Game?

A natural question arises: when will this end? Clearly, with massive cost-side investments, the core issue is not simply whether revenue growth can match training cost increases but, more importantly, when models will no longer require such massive investments or such rapid iteration.

For large model technology itself, the point when investments are no longer needed is when the scaling law fails. In other words, when the computational power required for a slight increase in intelligence begins to surge exponentially, the necessity for model training diminishes.

When models no longer require frequent training iterations, it also means the end of high-density training capital investments. After investing in a new generation of models, this generation can generate revenue for 10 or even more years. When models no longer require training investments but can continuously generate revenue, a business model similar to "Yangtze Power" emerges.

However, the fundamental premise of this hypothesis is that leading large model manufacturers have outlasted numerous competitors in the protracted battle of capital, manpower, and data consumption. With only a few remaining rivals reaching a tacit understanding to cease price wars, an oligopoly market similar to the current cloud services market, with highly concentrated market share, will eventually form. In this scenario, the business model of large models will naturally become viable.

4) Before the Final Showdown: A Brutal Capital Game

Until the moment when the scaling law loses its efficacy, large model companies will remain insatiable consumers of capital. Under such circumstances, the competition for business models essentially transforms into a relentless capital race for continuous financing.

Of course, if a large model company can truly turn financing into a differentiated survival capability, akin to NIO, it would indeed constitute a core competency. However, for most companies, financing is not a game of greater fool theory. Capital's willingness to invest is inherently contingent upon a company's product and execution capabilities. Successfully raising funds with escalating valuations is, in itself, a process of mutual selection.

According to media reports, China's model war has evolved from an initial clash of a hundred models to a quintet of dominant players: ByteDance, Alibaba, JieYue, ZhiPu, and DeepSeek.

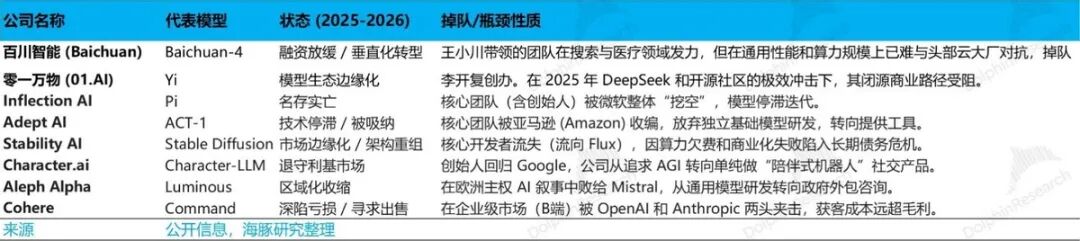

Among the original 'Six Little Dragons' of model startups—JieYue, ZhiPu, MiniMax, Baichuan Intelligence, Yuezhi Dark Face, and Lingyi Wanwu—Lingyi Wanwu and Baichuan Intelligence have fallen behind after DeepSeek's overnight fame and its complete open-source disruption of model pricing.

Overseas, the landscape has similarly consolidated into a quintet of contenders: OpenAI, Anthropic, Google Gemini, xAI, and Meta Llama. Even Meta's model has started to lag behind.

Some companies have sustained their financing and seen their valuations soar, while others have rapidly perished along the way. From the perspective of large model survival, the ability to secure financing is ultimately a result of the combined effects of core talent, model strength, and product implementation progress.

Core talent remains at the center of a billion-dollar AI talent acquisition race, which is still ongoing. The other two factors hinge on the model's intelligence level and, ultimately, its ability to generate revenue.

1) Model Strength:

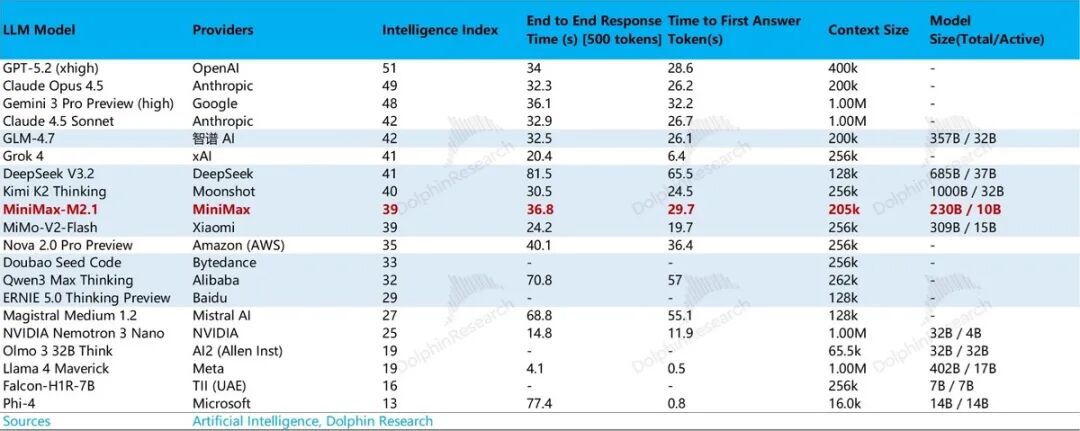

As seen below, model startups that have survived typically rank prominently on model leaderboards. This is attributed to their competitive edge across various granular metrics (model intelligence level, hallucination rate, model parameters, waiting time before the first token output in responses, etc.).

2) Product Implementation Capability

Over the past year, most independent startups have either lost talent to internet giants, struggled to generate revenue from product implementations, or been outcompeted by cost-effective open-source models in pricing battles, causing them to fade away.

In a nutshell, before and even for some time after the 'dawn' when the Scaling Law hits a wall, we will witness models succumbing one by one in the three-dimensional competition of 'talent acquisition, model development, and product implementation.'

The true contenders reaching the finals will be determined not only by talent and financial backing but, more critically, by the progress of model development and the level of product implementation.

In the next analysis, Dolphin Research will delve into ZhiPu and MiniMax's model and product implementations to understand how to evaluate the capital market value of large models.

- END -

// Reprint Authorization

This article is an original piece by Dolphin Research. Authorization is required for reprinting.

// Disclaimer and General Disclosure

This report is intended solely for general comprehensive data purposes, serving users of Dolphin Research and its affiliated institutions for general reading and data reference. It does not consider the specific investment objectives, investment product preferences, risk tolerance, financial situation, or special needs of any individual receiving this report. Investors must consult with independent professional advisors before making investment decisions based on this report. Any person making investment decisions using or referring to the content or information mentioned in this report assumes their own risk. Dolphin Research shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect liabilities or losses arising from the use of the data contained in this report. The information and data in this report are based on publicly available sources and are provided for reference purposes only. Dolphin Research strives for, but does not guarantee, the reliability, accuracy, and completeness of the relevant information and data.

The information or views mentioned in this report shall not be considered or construed as an offer to sell securities or an invitation to buy or sell securities in any jurisdiction. They also do not constitute advice, inquiries, or recommendations regarding relevant securities or related financial instruments. The information, tools, and materials in this report are not intended for, or proposed to be distributed to, citizens or residents of jurisdictions where the distribution, publication, provision, or use of such information, tools, and materials contradicts applicable laws or regulations, or would require Dolphin Research and/or its subsidiaries or affiliated companies to comply with any registration or licensing requirements in such jurisdictions.

This report merely reflects the personal views, insights, and analytical methods of the relevant creators and does not represent the stance of Dolphin Research and/or its affiliated institutions.

This report is produced by Dolphin Research, and its copyright is solely owned by Dolphin Research. Without prior written consent from Dolphin Research, no institution or individual shall (i) produce, copy, duplicate, reproduce, forward, or distribute in any form of copies or replicas in any way, and/or (ii) directly or indirectly redistribute or transfer to other unauthorized persons. Dolphin Research reserves all related rights.