How Does End-to-End Architecture Make Autonomous Driving More Like That of an Experienced Driver?

![]() 01/21 2026

01/21 2026

![]() 471

471

If we liken the development history of autonomous driving to human learning, then for a considerable period, this 'student' has been cramming with extremely cumbersome doctrines. During this stage, autonomous driving systems employed a modular architecture heavily reliant on tens of thousands of handwritten logical rules. For instance, if a pedestrian is crossing the road, you brake; if the car ahead signals a left turn, you slightly decelerate; if you see a yellow light flashing, you assess whether the distance allows for a stop. This method may suffice in logically simple closed campuses or highly structured highways, but it falters in unpredictable urban downtown areas.

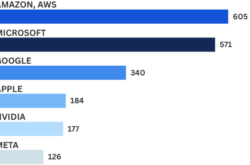

The primary reason the autonomous driving industry has collectively moved towards 'end-to-end' architecture in the past two years is that everyone has finally recognized that the complexity of the real world cannot be fully captured through manual enumeration. The essence of end-to-end architecture lies in its ability to directly map 'signal input' to 'control output'. In simpler terms, it transforms the car from a machine executing programs based on instructions into an intelligent agent with 'driving intuition'.

This driving intuition is not dictated by lines of code typed out one by one. Instead, it stems from the neural network's self-developed muscle memory, gained from observing millions of hours of human driving videos. Tesla's FSD v12 version broke through the limitations of traditional algorithms by replacing over 300,000 lines of complex C++ code with a unified neural network, resulting in unprecedentedly smooth intelligent driving performance.

Differences Between Traditional Architecture and End-to-End

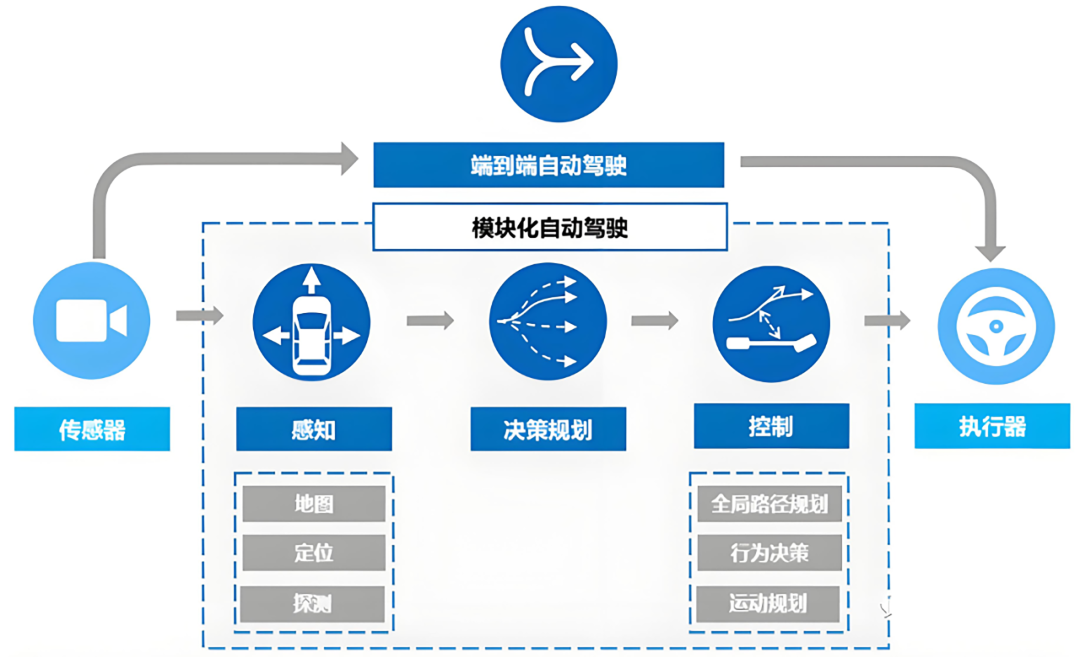

To comprehend what end-to-end architecture resolves, we must first understand the specific issues with traditional architecture. In traditional architecture, the perception module functions like the car's 'eyes,' observing the scene, converting perceived obstacles into simple geometric shapes, and providing a set of coordinates to the planning and control module.

However, this approach has a critical flaw: once the perception module identifies an object ahead as a 'rectangular box,' it discards many detailed pieces of information about the object. For example, if a pedestrian is seen looking back at the car or preparing to accelerate and run, these subtle dynamics are lost during the simplification into coordinates. The planning and control module only receives dry, possibly erroneous abstract data, akin to a person blindfolded and relying on a poorly translated secondhand account of road conditions, leading to hesitant and cautious decision-making.

In contrast, end-to-end architecture allows data to flow within the neural network as high-dimensional features, without any information being forcibly 'translated' or 'truncated.' This means the system can directly perceive subtle environmental cues that are difficult to define verbally, such as the reflection of sunlight on the road, the illusion created by water puddles, or the moment a vehicle ahead's brake lights illuminate. All these cues are directly translated into decision-making control bases.

Differences between Modular and End-to-End Autonomous Driving, Image Source: Internet

This 'perception-decision' integrated design enables the autonomous driving system to undergo global optimization during training, rather than each module focusing solely on its own tasks. It works towards an ultimate goal, namely 'driving smoothly and safely like a human.'

This globally optimized logic brings about transformative improvements. In traditional architecture, a perception module error might merely stem from a 2% drop in target recognition rate, but this 2% error can trigger an abrupt stop when passed to the planning and control module. However, in end-to-end architecture, the system possesses strong fault tolerance and 'self-repair' capabilities. During learning, it understands which visual features are crucial to driving outcomes and which can be ignored as noise.

Take the UniAD model as an example; it integrates tasks such as target detection, trajectory tracking, mapping, and planning within a unified Transformer framework. All components communicate within the same BEV (Bird's Eye View) feature space. When the prediction module estimates others' routes, it simultaneously considers where the self-driving car intends to go, making the autonomous driving perception and decision-making process extremely efficient. This allows the intelligent driving system to behave more like an experienced driver in complex scenarios such as lane changes and unprotected left turns.

Architecture Comparison Dimensions

Traditional Modular Architecture (Modular System) vs. End-to-End Neural Network Architecture (End-to-End System)

Logical Basis

- Traditional: Based on artificial hard-coded 'If-Then' rules

- End-to-End: Neural network self-learning based on large-scale human driving data

Information Loss

- Traditional: Significant information loss due to module-to-module transmission via defined interfaces (e.g., coordinates, labels)

- End-to-End: Global feature vector flow preserves subtle semantics from original sensors

Long-Tail Scenario Handling

- Traditional: Heavily reliant on patch code, difficult to cover edge cases

- End-to-End: Possesses cross-scenario generalization ability, can handle unseen abnormal conditions

Optimization Strategy

- Traditional: Local optimization, inconsistent or conflicting module goals

- End-to-End: Global joint optimization with trajectory planning as the sole ultimate goal

Update Speed

- Traditional: Extremely slow, requires manual parameter tuning and logical chain verification

- End-to-End: Extremely fast, automatically evolves through increased high-quality data and computing power

Response Latency

- Traditional: High and unstable latency due to module serial processing

- End-to-End: Fixed single inference cycle, response time typically in milliseconds

Differences Between Traditional Architecture and End-to-End

End-to-End Endows Machines with Physical Intuition

If end-to-end merely imitates human operations, it cannot be considered fully intelligent. To become a true veteran driver, one must be able to 'anticipate' the future, simulating all possible scenarios that may occur in the next few seconds in one's mind. In the development path of end-to-end technology, the incorporation of world models is equivalent to installing a 'brain simulator' in the system.

This model no longer rote memorizes what the road looks like but learns the physical laws of the real world by observing vast amounts of video data. It knows that after a ball rolls out, a child is likely to follow, and it also understands that braking distance increases in rainy conditions. The essence of world models is a generative artificial intelligence capable of predicting and generating various possible future evolution paths based on the current scene.

This predictive ability is crucial for addressing the most challenging 'long-tail scenarios' in autonomous driving. Traditional algorithms, when encountering unfamiliar construction sites or bizarre traffic accident scenes, may directly 'strike' or drive erratically due to the lack of corresponding code instructions. However, an end-to-end system equipped with a world model can infer, based on its common-sense understanding of the physical world, that those obstacles are impassable.

More interestingly, world models not only assist in decision-making but also serve as extremely powerful 'data simulators.' Collecting extreme and dangerous scenarios in reality is extremely costly and dangerous. However, within the neural network, world models can create thousands of logically consistent hazardous scenarios out of thin air, allowing end-to-end models to intensively train in these created scenarios. This closed loop of extracting laws from reality and feeding them back into virtual training accelerates the evolution of autonomous driving hundreds of times faster than relying solely on real-world mileage accumulation.

Complementing world models is the 3D occupancy network (Occupancy Network), another powerful tool for spatial perception in end-to-end architecture. Previous autonomous driving systems were accustomed to viewing the world as specific types of 'objects,' such as cars, people, and trees. However, this mindset is too narrow. If encountering a strangely shaped sculpture on the road or a large wooden crate fallen from a truck, the system might choose to ignore it because it cannot recognize what it is.

The 3D occupancy network effectively solves this problem by not caring what the obstacle is; it merely divides space into countless tiny voxels and determines whether each cell is occupied. This endows the car with 'geometric intuition,' causing it to avoid any occupied space, regardless of what it contains. This obstacle avoidance method, independent of semantic labels, significantly enhances the safety baseline of end-to-end systems, enabling autonomous vehicles to maintain good driving performance in diverse urban scenarios.

The Inevitable Black-Box Problem of End-to-End

Although end-to-end systems can exhibit the 'driving sense' of experienced drivers, they face an inevitable issue: the inexplicable 'black box.' If a traditional modular system is involved in an accident, logs can be reviewed to precisely locate the fault. However, in a neural network with hundreds of millions of parameters, the steering wheel turning left by one degree may be influenced by multiple factors, and no one can definitively say why. This 'inexplicability' is the biggest obstacle to the implementation of end-to-end systems.

To address this issue, technologies have attempted to introduce an anthropomorphic architectural design, drawing inspiration from the 'fast and slow system' theory proposed by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman. In this architecture, the end-to-end neural network acts as 'System 1,' responsible for millisecond-level intuitive reactions. To counterbalance this intuition, an external 'System 2' is added, namely a safety defense layer based on visual language models (VLMs) or hard-coded rules.

System 2 acts like a coach sitting in the passenger seat, capable of understanding explicit symbolic rules such as 'do not run red lights' and 'do not enter one-way streets,' as well as using logical reasoning to judge whether System 1's operations comply with norms. If the end-to-end model makes a dangerous move due to misleading features, System 2 will forcibly cut off control and execute a safe maneuver or emergency stop through preset physical safety rules. This strategy of 'neural networks handling the upper limit and traditional rules handling the lower limit' is currently the optimal solution for the mass production and implementation of end-to-end technology.

Following this logic, the evolution of end-to-end is reshaping the entire automotive industry. Previously, autonomous driving teams were dominated by C++ engineers writing logical code. However, now, the most core roles have shifted to data and computing power operation and maintenance experts. The strength of an autonomous driving system no longer depends on who writes more sophisticated code but on who can more efficiently filter out high-quality driving videos and who can build larger GPU training clusters. This transformation has turned the competition in autonomous driving into a battle of resources. Only enterprises with millions of installations and the ability to form closed-loop data flows can continuously iterate, making their systems more and more like 'veteran drivers' with each version update.

What Challenges Does the Implementation of End-to-End Bring?

When we examine the development of autonomous driving from a higher perspective, we find that end-to-end architecture is attempting to solve an ultimate challenge in artificial intelligence: how to enable machines to understand common sense. Scenarios such as being cautious when seeing a ball roll onto the roadside due to the likelihood of a child following, or maintaining a safe distance from large trucks in rainy conditions, were previously scenarios that required engineers to painstakingly design logical conditions for.

End-to-end, through learning from vast amounts of real-world data, has accumulated a kind of 'common sense of the physical world' within the neural network. When this common sense accumulates to a certain extent, the system exhibits human-like intelligence, knowing how to yield to pedestrians and how to find gaps in complex lane merges. This evolution is not constrained by artificial programming; its only boundaries are the richness of the data and the ceiling of computing power.

Of course, end-to-end architecture demands extremely high-quality data. If fed with a large amount of mediocre or uninformative driving videos, the trained model will only be a 'mediocre driver.' Additionally, to support the reasoning of such large-scale models, the memory bandwidth and computing power overhead of onboard chips have become necessary hard costs.

Especially as the system becomes more and more human-like, how should human society construct a new set of evaluation and liability determination standards? When a black-box model makes a violation, how can we accurately correct it without producing side effects? These questions are still under exploration.

However, it is undeniable that end-to-end architecture has pointed the way towards higher-level intelligence for autonomous driving. By eliminating information barriers between modules and utilizing global optimization, it breaks through the limits of human logic. With the further deep integration of world models, large language models, and end-to-end architecture, future intelligent driving systems will not only be able to see the road clearly but also 'understand' this complex and ever-changing human world. This transition from 'machine driving' to 'human-like intelligent driving' is precisely the core answer that end-to-end technology brings us.

-- END --